To learn more about how Vietnam has achieved almost universal education at a relatively high level of quality in a developing country of over 100 million people, I visited Hanoi last year and talked to a variety of Vietnamese educators, policymakers and researchers. My conversation with Phương Lương Minh and Lân Đỗ Đức at the Vietnam National Institute of Educational Sciences (VNIES) was especially instructive in providing insights into how schooling in Vietnam has improved in rural areas with ethnic minority students. The second part of this conversation looks ahead and discusses what might happen in the future as Vietnam rolls out a new competency-based curriculum and related textbooks. The first part discussed the efforts to improve education in Vietnam over the past thirty years, particularly in ethnic minority areas. For related posts, see the Lead the Change Interview with Phương Minh Lương and A Conversation with Chi Hieu Nguyen about Vietnam’s responses to the COVID-19 school closures

Lân Đỗ Đức is the Vice Director, The Department of Scientific Management, Training, and International Cooperation at The Vietnam National Institute of Educational Sciences. Phương Lương Minh is a lecturer and coordinator of the Master Program of Global Leadership, Vietnam Japan University (Vietnam National University), and a collaborating researcher at the Vietnam National Institute of Educational Sciences. I am indebted to President Mai Lan and colleagues at VinUniversity for making this trip possible, and to Dr. Le Anh Vinh, Director General of the Vietnam Institute of Educational Sciences (VNIES) and his colleagues for their support.

– Thomas Hatch

Looking toward the future of educational improvement in Vietnam

Thomas Hatch (TH): “High-performing” education systems like those in Finland and Singapore have struggled to move to a system that is less exam-driven and that embraces a more active, student-centered pedagogy. Research in Singapore suggests that a kind of hybrid pedagogy has emerged that maintains some traditional practices but has some of the features of active methods as well. What do you expect will happen in classrooms as Vietnam implements the new competency-based curriculum?

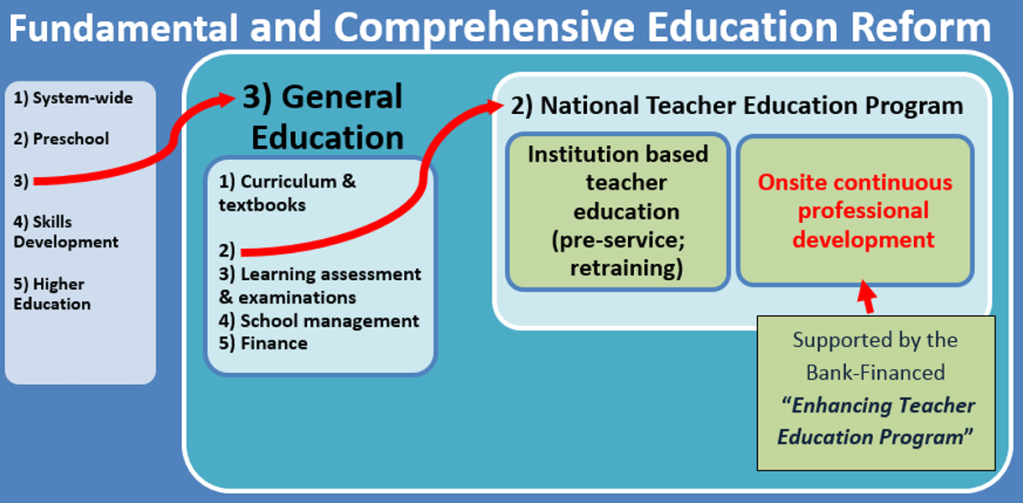

Lân Đỗ Đức (LDD): Good question! Asian countries have a Confucian tradition where learning is the top priority. We have great respect for teachers. The traditional teaching style is common across countries. Now in Vietnam, as of 2021-22, we have 1.4 million teachers. Although the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) allocated a lot of resources and carries out professional development programs like the Enhancing Teacher Education Program (ETEP – funded by the World Bank) it’s likely not all are fully able to adopt new methods well. Professional development is a huge, ongoing effort. We hope most Vietnamese teachers are willing to change, but we lack evidence.

Phương Lương Minh (PML): I can share some findings from our report on technology in education conducted for UNESCO. After COVID, there was actually a positive impact on teacher professional development. We have seen that there are now substantial open resources for teachers, even in remote areas there are online learning systems and open resource centers available to them. The teachers now can learn from all the lesson plans already uploaded into the network and shared. We have heard from teachers who think this is really amazing. Even with over 1 million teachers, many can access these platforms. Some of these platforms are controlled by the Ministry of Education, but some are also from private providers. Of course, if creators want official approval, they need to propose learning materials for verification by the Ministry.

TH: Are people in ethnic minority and rural areas aware of the competency-based curriculum change and the change in textbooks? Will it be easier to make this change in rural areas?

PML: I have not had the chance to see this from my own observations, but I have seen that in remote areas parents often are not close enough to see their children’s education or to know what they are learning or what textbooks they are using. For preschool and primary school, until grade 3, children attend satellite village schools and live at home. But after grade 3, they go to boarding schools located in larger communities, far from their home villages. In some villages that are big enough, they may have schools that go through 4th or 5th grade before children move to boarding schools. The boarding schools are usually far from the villages, in the commune center. The students stay there all week, and they only go home on the weekends so then the parents have no chance to know about the curriculum and the textbooks in the higher grades.

“in remote areas parents often are not close enough to see their children’s education or to know what they are learning or what textbooks they are using.”

LDD: Depending on the population and number of students in an area, there might be two or three primary schools. When students complete 3rd grade, they transfer to boarding schools that serve as centers for the higher grades. When students transition to secondary school, they may attend boarding schools at that level as well.When boarding schools start depends on the population density in the area. Some places have boarding schools from 4th grade onwards. Others may start at 6th grade or even later.Boarding schools could potentially start as late as 10th grade at the upper secondary level, but not all students continue to 10th grade.

TH: I wonder what you predict might happen as Vietnam rolls-out the shift to a competency-based curriculum and textbooks. In ethnic minority areas, do you think teachers might resist or parents might worry their children won’t succeed? Or might it actually be easier to make that shift in rural schools?

LDD: This is something that we hope to study, but I expect there will be varying levels of challenge in different areas. However, I think the willingness of the Vietnamese people to change is high. We really want to change because we that see that many students now don’t have the skills they need for higher education or for vocational education, so we hope the new competency-based curriculum will better prepare students. From 2022-2025 MOET will assign provinces to conduct research on implementation and outcomes. We are very interested in understanding local perspectives on coordination and real impacts, especially in rural and ethnic minority areas. The willingness for change gives me optimism, but we also need to closely study results on the ground.

Chau Doan/World Bank is licenced under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

PML: In our research with the RISE Programme we planned to explore how the new competency-based curriculum was implemented in schools, but because of COVID, the implementation of the new textbooks was delayed. However, in our earlier qualitative longitudinal study we looked at teachers’ and headmasters’ understanding and perspectives on competency-based teaching. The majority have a very clear understanding the objectives of the lessons and the knowledge and skills when asked about the competencies they don’t have a very clear distinction between skills and competencies. Actually, when we looked at in practice, some teachers were doing competency-based teaching in their classroom, but they did not realize it.

“when we looked at in practice, some teachers were doing competency-based teaching in their classroom, but they did not realize it.”

TH: Help me understand what that looks like. How could you tell they were already teaching competencies without realizing it?

PML: We collected video recordings of lessons along with the lesson plan and an interview with the teacher before the class and an interview afterward where they watch the recording and reflect afterwards. We ask them what were the competencies that they were teaching. The lesson plans they were designing were still based on the old knowledge-based textbooks not the new curriculum, and we recorded this and had the post-interview, and we could see the teachers were teaching some competencies like creativity and critical thinking in their teaching activities. They still followed the textbook but they changed the pedagogy. They designed the teaching by themselves.

TH: But what led them to change their pedagogy? Was it the professional development?

PML: It depends on the individual. Usually, the government’s training is common, but the pedagogy for each lesson depends on each teacher, and the teaching method of the teachers from the rural provinces is different from that of those in the central region so we have to see what are the reasons for these differences: Why can’t the teachers from the Northern provinces teach the competencies as well as those from the central region? From that maybe we can get back to the professional development training delivered by the government and whether that was different or not. Or whether the networking in one school or region is different.

LDD: These videos were collected before COVID around 2017, and the government has had strong, continuous professional development training every year, and they have had a focus on “active pedagogy” even before they began the comprehensive renovation of the curriculum. The Ministry of Education actually promoted active teaching methods since the 2000s when we conducted the previous education reform. A lot of the civil society organizations in Vietnam also supported the educators in all the provinces to promote active teaching methods. It is not new. It is not that we changed to the competency-based curriculum, and then we promoted active teaching. Active teaching existed in the previous education reform.

It is not that we changed to the competency-based curriculum, and then we promoted active teaching. Active teaching existed in the previous education reform.

Next steps?

TH: What do you see as the next step Vietnam needs to take to continue improving its education for all students?

PML: For me, the most important thing is still teachers. We cannot wait for support from the government or Ministry. What happens in the classroom still comes down to each teacher and child. Supporting training for teachers is critically important so that they enjoy their job and have the inspiration to improve their teaching. That’s why it’s good that we have open resources for them and now, with the Internet, they can easily learn and share with their colleagues from all corners of the country. I think we will be able to make changes very quickly if we can promote this online platform and provide open resources.

LDD: Along with teachers and human resources overall, I think in the coming years Vietnam has to deal with a number of economic issues so at the macro level we need to maintain enough investment in education. But we need to define the top priorities because we have limited resources, and we cannot do everything at once. In recent years, we have focused on changing the preschool. We have a plan, , and VNIES is charged with writing the new preschool curriculum, and it is going to be introduced next year, and we are going to have a pilot from 2025 to 2027. But, for me, for the next 10 years, I think higher education should be a priority. I don’t see many colleges or universities in Vietnam at a high rank.