What can be done to reduce some of the barriers that limit students’ post-high school opportunities? In the second part of this two-part series, RJ Wicks scans recent news and research from the US to survey some of the “micro-innovations” that may help to expand the pathways into college and productive careers. The first part of this scan reviewed the current conditions for students in the US as they try to find their way into college and the workforce.

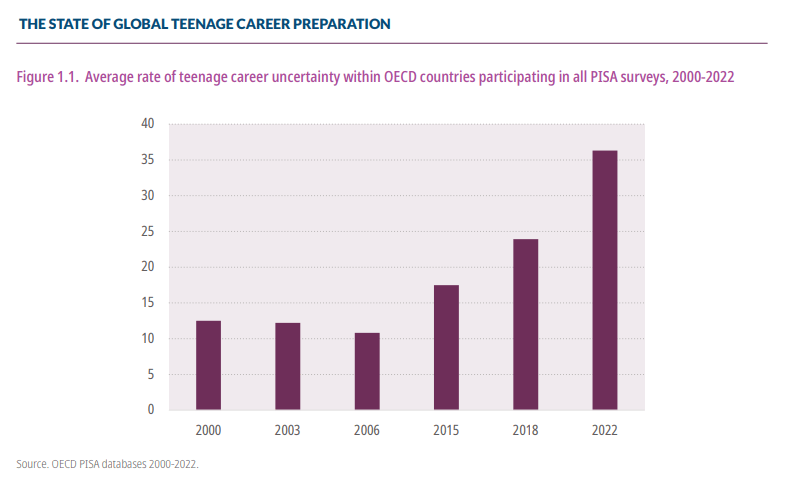

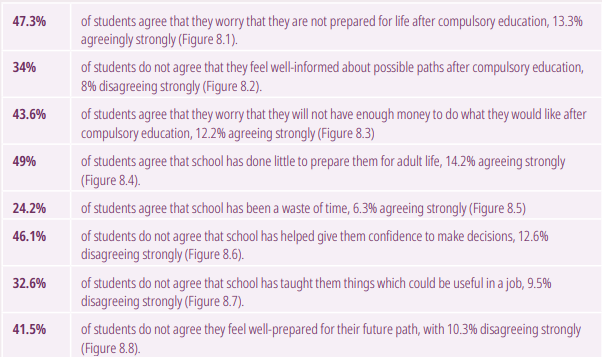

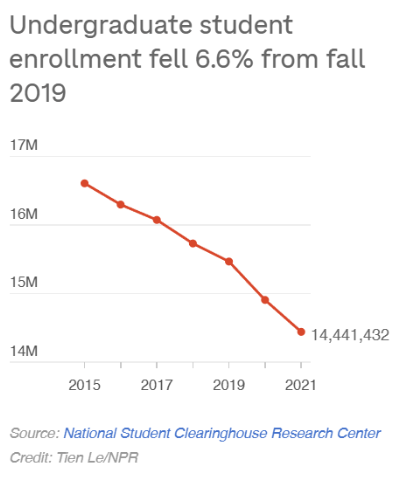

COVID-19 accelerated longstanding challenges: college enrollment dropped especially at community colleges; financial insecurity forced some students to pause or leave school; equity gaps widened; and reports continue to suggest that many students are unprepared for life after high school. Yet educators are also developing a host of innovative practices and programs that are helping to address these and other issues. Initiatives such as guaranteed admissions, promise programs, career and technical education (CTE), dual enrollment offerings, early college high schools, and work-based learning are demonstrating the potential to create new and smoother pathways into post-secondary academic and professional environments

Guaranteed Admissions Programs

Guaranteed admissions programs seek to make college admissions more automatic and less selective by reaching out to students who meet admissions criteria and offering them a place. For example, a number of higher education institutions in Michigan formed the Michigan Assured Admission Pact (MAAP), which provides guaranteed admission to students graduating from a Michigan high school if they have earned a cumulative high school grade point average of 3.0 or above. Related state programs include Admit Utah, Washington State’s Guaranteed Admissions Program, University of Texas Top 10% Rule, Direct Admission Minnesota, and SUNY’s Top 10% Promise.

Promise Programs

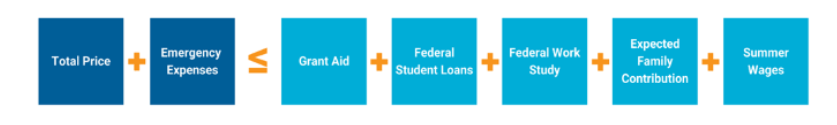

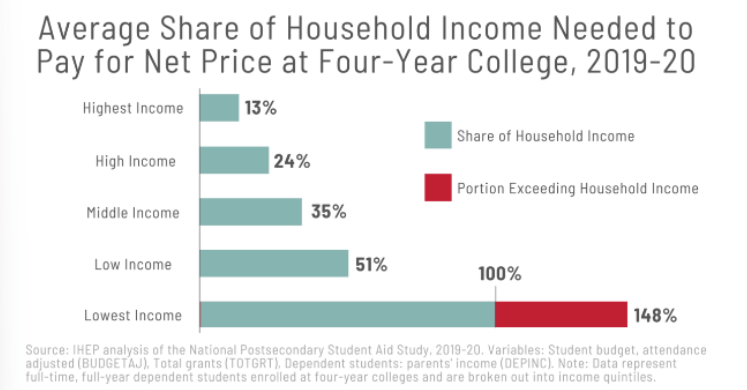

Promise programs are tuition-assistance initiatives designed to increase access to higher education, particularly for low-income and underrepresented students. These programs often eliminate financial barriers by covering remaining tuition costs after other financial aid has been applied, effectively making college more accessible and affordable. As of 2023, there are over 400 promise programs across the United States with research-to- date suggesting that the most effective offer free or reduced-cost college tuition along with structured advising, explicit communication and messaging, and outreach. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, all 50 states have at least one local or statewide program. Exhibiting a variety of different approaches, promise programs include “last-dollar” programs that fill in tuition gaps left after other aid has been used, as well as “first-dollar” programs that provide tuition support upfront. In some cases, in addition to covering tuition costs, some programs provide additional support for the many other expenses that can make completing college difficult.

A study of 33 public community college promise programs across the U.S. found that these initiatives significantly increased enrollment among first-time, full-time students, with the largest gains seen among Black, Hispanic, and female students. According to that same study, initial first-time enrollment rose by 47% for Black men and 51% for Black women, while enrollment for Hispanic men and women increased by 40% and 52%, respectively.

- Kalamazoo Promise is a first-dollar, place-based scholarship that covers up to 100% of tuition at any public—and select private—college or university in Michigan for students who graduate from Kalamazoo Public Schools. The program requires continuous enrollment in the district since at least ninth grade. Since its launch, it has led to a 14-percentage point increase in college enrollment overall and a 34-point increase for four-year college enrollment. Students in the program attempt more college credits—15% more in the first two years—and are more likely to complete a degree: six years after high school, credential attainment rose from 36% to 48%, driven largely by bachelor’s degrees. The program’s positive impacts were especially significant for low-income, nonwhite students, and women. Economically, the Promise has yielded an estimated 11% internal rate of return in lifetime earnings.

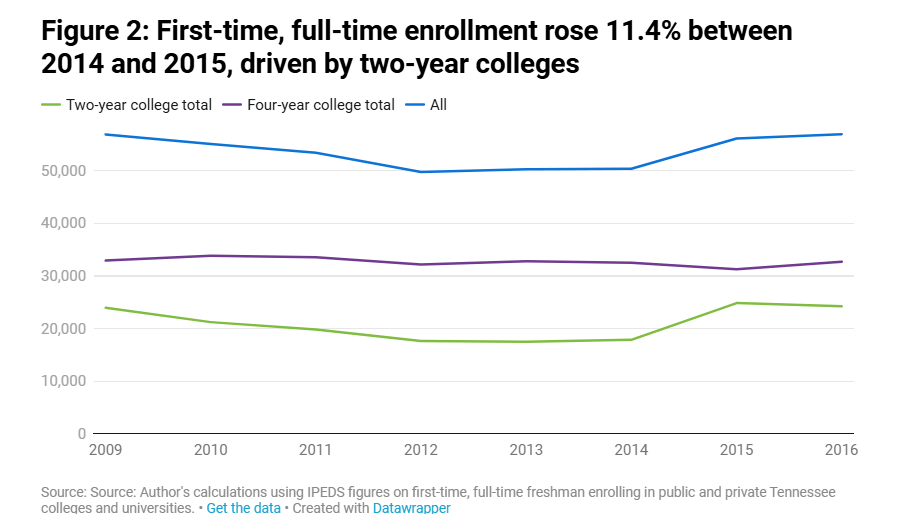

- Tennessee Promise offers last-dollar scholarships for community and technical colleges that covers remaining tuition costs after federal and state financial aid is applied. In addition, the program requires students to participate in mentoring initiatives to 1) help them with completion of financial aid forms (FAFSA); 2) guide them through the college application process; and 3) provide ongoing support once enrolled. To foster a culture of accountability and civic engagement, students must complete eight hours of community service each semester and maintain a minimum GPA of 2.0. The program contributed to a 11.4% increase in first-time freshmen enrollment at community colleges in Tennessee in its inaugural year. The program also helped increase retention rates and improve college completion. Over 125,000 students benefited from the program in its first decade.

- Milwaukee Area Technical College (MATC) Promise combines financial support with in-school FAFSA workshops and student-facing messaging that explicitly states “Free Tuition” to reduce confusion and anxiety about the affordability of college. MATC also offers last-dollar scholarships for students. With this approach, on-time FAFSA completion rates rose by 5 percentage points and college matriculation among low-income students increased by 6 to 7 percentage points.

- CUNY ASAP (Accelerated Study in Associate Programs) is a last-dollar program for NYC/ New York State residents that offers a full package of support: free tuition, textbook stipends, unlimited transit passes, dedicated academic advisors, and career counseling. In a 2015 study across three New York City community colleges, ASAP students earned on average 9 more credits, graduated at rates 18 percentage points higher than a control group, and were 8 percentage points more likely to transfer to a four-year institution. CUNY ASAP reports a three-year graduation rate of 53 percent – more than double that of comparable peers. ASAP’s success has inspired similar efforts in Ohio, West Virginia, and California, where adaptations like gas cards for rural students are helping extend the model’s impact.

Early College and Dual Enrollment Pathways

Dual enrollment and early college high school programs offer high school students unique opportunities to earn college credits, reducing the time and cost required to attain a degree. While both initiatives aim to improve access to higher education, they differ in structure and outcomes. Dual enrollment allows students to take college-level courses alongside their high school curriculum. In contrast, early college high schools are structured programs where students can earn both a high school diploma and up to two years of college credit, often on a college campus and with integrated support systems. A study by the American Institutes for Research found that 84% of early college students enrolled in college after high school graduation, compared to 77% of their peers. Additionally, 45% of early college students earned a college degree within six years, compared to 34% of the control group.

By getting students into college-level coursework before graduation, these programs aim to help students build momentum and save money. They also provide what can be called “stacked supports” across sectors. In the process, they intend to break down silos and align expectations across K-12, higher ed, and workforce systems. Some studies point to specific benefits for students in these programs, including increased college enrollment and completion rates, particularly among underrepresented groups.

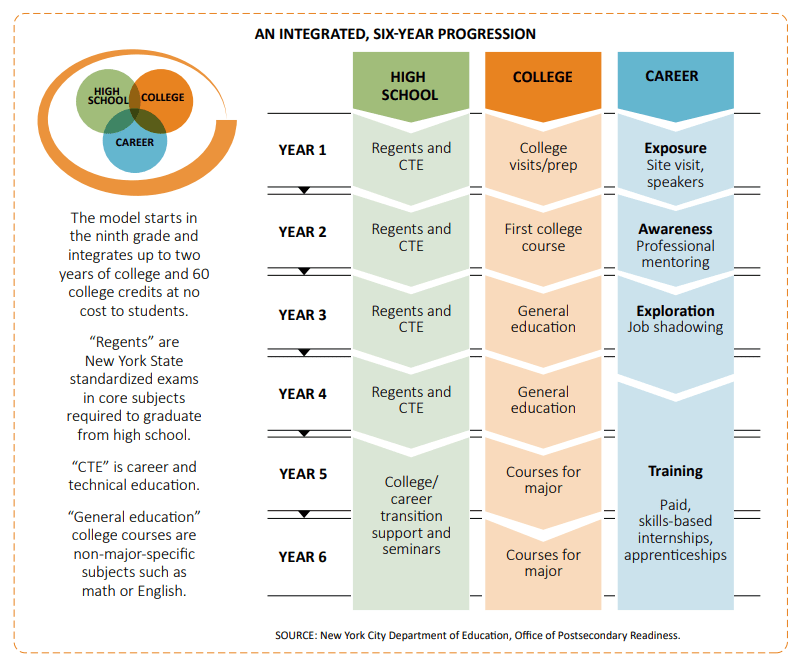

- P-TECH (Pathways in Technology Early College High School) provides a six-year program where students earn both a high school diploma and a no-cost associate degree, all while working in “real world” placements in partnerships with companies like IBM. Launched in 2011 in Brooklyn, New York, through a collaboration between IBM, the New York City Department of Education, and the City University of New York, P-TECH provides a single high school program where students can take college-level coursework and build technical skills and receive industry mentorship in industries such as health IT and energy technology at the same time. In 2023, one evaluation of the model found that, seven years after entering high school, students in New York City’s P-TECH 9-14 program were 5 percentage points more likely to earn an associate’s degree — results driven particularly by young men, 13% of whom completed a degree compared to just 3% of their peers in other NYC high schools. After a 2014 visit by the Australian Prime Minister, Australia opened two P-TECH schools and since then the P-TECH network has grown to include 300 schools in 26 countries.

- Boston Public Schools’ $38M Healthcare Career Training Expansion strives to build career pipelines in critical fields by embedding healthcare education directly into the high school experience. Students can begin focusing on a healthcare specialty as early as 10th grade and participate in hands-on training, job shadowing, and simulation labs. The initiative includes:

- Specialized vocational academies tailored to healthcare careers;

- Dual enrollment opportunities that allow students to earn college credit;

- Paid summer internships at leading hospital systems like Mass General Brigham.

- Boston’s program is part of a broader $250 million Bloomberg initiative across ten major U.S. cities.

Key Micro-innovations helping get students into and through college/career pathways

Although the promise programs and dual enrollment and early college programs often strive to provide comprehensive support, they also encompass some seemingly small but strategic design choices that can be implemented on their own or in concert with other innovations.

- Mandatory mentorship and coaching. A number of Promise Programs assign trained mentors or success coaches to ensure students receive personal guidance—not just information. For example, Detroit Promise pairs each student with a full-time Campus Success Coach who provides personalized support, connects them to campus resources, and helps them overcome common barriers to persistence. This human connection helps demystify systems and boosts retention.

- Just-in-time financial support. For many students, non-tuition costs – even a few hundred dollars – can serve as major barriers to completing courses and degrees. In anticipation of these financial burdens and to remove barriers before students hit a crisis point some promise programs, like CUNY ASAP, provide textbook and transport subsidies. Georgia State University’s Panther Retention Grants provides small amounts of financial support (“micro-grants”) to students with outstanding balances that would otherwise prevent them from registering for classes.

- Proactive communication and “nudges.” MATC’s FAFSA workshops and Admit Utah’s centralized digital tools make complex processes easier to understand, especially for first-gen or low-income students who may lack application support at home or school.

- Using technology to support the college application process. Admit Utah uses technology to close “guidance gaps,” recognizing many high school students may not have access to counselors or college guidance. To do so, Admit Utah provides a centralized online platform where students can explore college options, learn about scholarships and financial aid, and use AI-powered tools to navigate the application process.

- Contextualized career learning. Boston’s healthcare pathways and P-TECH embed industry-aligned experiences – job shadowing, internships, and certifications – within the high school curriculum, helping students see the relevance of their education and build employable skills early.

- Clear, student-friendly messaging. MATC’s “Free Tuition” campaign doesn’t just market affordability – it shapes perceptions and expectations about who belongs in college, often reaching students who wouldn’t have otherwise applied.

Acknowledging the challenges and continuing to expand the options

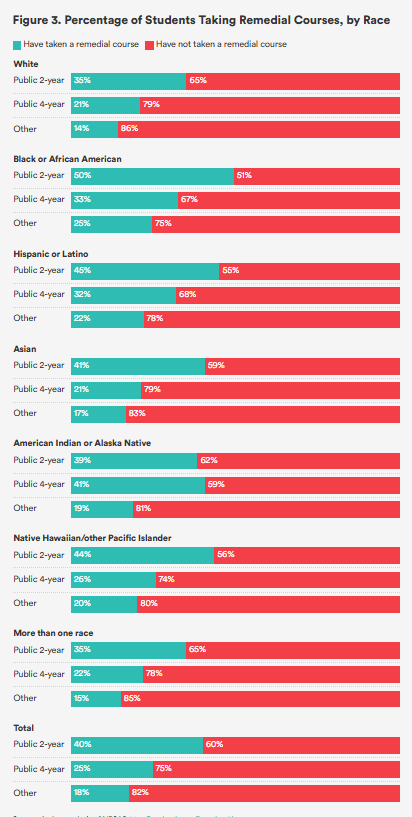

As momentum builds around some of these new pathways into post-secondary success, challenges remain. Despite its growing popularity, access to dual enrollment remains uneven. Black and Hispanic students, English learners, and students with disabilities are consistently underrepresented. Key barriers include lack of funding, which shifts costs like tuition and textbooks onto students; limited access in schools serving low-income communities; inadequate advising; and a shortage of qualified instructors—often due to strict credential requirements for teaching college-level courses in high schools. These gaps limit who benefits from dual enrollment and highlight the need for targeted support and structural investment.

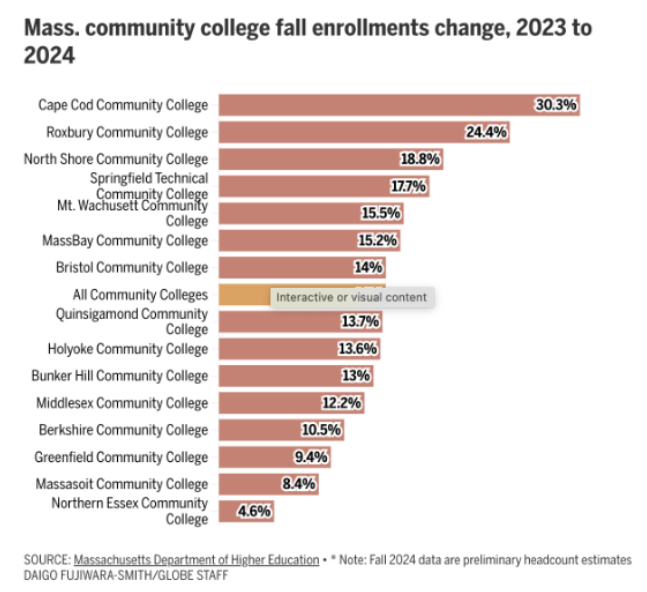

The popularity of free college programs can also quickly overwhelm campuses if they can’t keep up with the demands for more faculty, advisors, facilities, and other resources. MassEducate, for example, covers the full cost of tuition for eligible students at any of the state’s 15 community colleges and even provides allowances for some students who need help paying for books, supplies and other costs. Launched in the fall of 2024, the program already contributed to a 14% rise in community college enrollment, with some campuses reporting enrollment increases of almost a third in one year. Under these conditions, even program advocates are worried that students, particularly first generation college students, will drop out if hiring and support for faculty does not keep pace.

Furthermore, scaling does not always lead to success. For instance, Washington State’s efforts to replace high school exit exams with multiple graduation pathways encountered a number of implementation challenges. In 2023, after the changes were made, one in five seniors had no graduation pathway at all, and students in smaller or rural schools often lacked access to robust options. Some were funneled into lower-wage career tracks or military pathways by default, raising concerns about limited opportunity, inadequate guidance, and uneven access across schools and student populations. At the same time, despite the challenges, states are continuing to try to increase the options and scale them to as many students as possible. For instance, Colorado, Delaware, and Indiana are expanding career-focused high school experiences. Colorado’s 2021 Successful High School Transitions bill allows students in internships to count as full-time learners; Delaware’s Colonial School District fosters interdisciplinary collaboration through interconnected career pathways; and Indiana is redesigning its diploma to combine core academics with two years of pathway-specific learning and work-based experience. In North Carolina, Guilford County Schools’ Signature Career Academies are preparing students for rapidly growing fields like AI and biotechnology.

As these and other efforts to create new college and career pathways continue to grow, real progress will hinge on learning from what works, addressing persistent gaps, and ensuring every student has a structured path to postsecondary success.