This week, IEN reposts part 2 of a series of blog posts in which Larry Cuban reflects on the endurance of “two dominant patterns of organizing schools and teaching lessons” in the US: the age-graded school and “teacher-centered instruction.” In part 2, Cuban begins exploring whether the patterns he has seen in the US appear in other countries, in this case France. The original post appeared on Larry Cuban’s Blog on May 7th.

In Part 1, I asked the question whether or not the ways that U.S. schools have organized (i.e., the age-graded school) and the dominant ways that teachers teach in American classrooms (i.e., teacher-centered instruction) are unique to the U.S. So in a series of posts over the next few weeks, I will sample how different nations organize their systems of schooling and offer photos of classrooms and descriptions of lessons to see how actual students and teachers appear.

The organization of schools in other countries and photos of lessons suggest a strong similarity to the U.S.’s age-graded structures and classroom organization. While diagrams of a nation’s schools are helpful to readers in getting a sense of how each country organizes their public schools and while snapshots do convey how classroom furniture is arrayed, the importance of wall clocks, and national flags, neither charts nor photos tell viewers the ways these teachers teach multiple lessons thereby revealing patterns in teaching. Finally, snapshots fail to show student learning since they capture a mere instant of what a class is doing. So charts and photos can inform but they have definite limits.

Another shortcoming to relying upon photos is that I may have used non-representative samples of a nation’s classrooms, given that I pulled photos from the Internet. But those photos are all I have at the moment. I do invite readers to offer other photos and text that challenge the generalizations I make about school structures, given the limited evidence I offer.

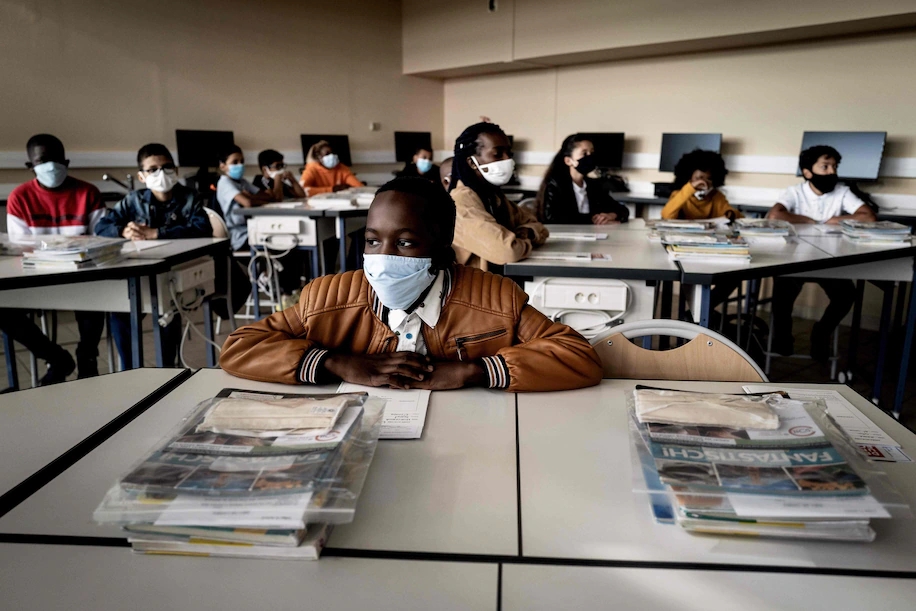

In this post, I will focus on one country–France–and offer photos of “typical” public school classrooms over the past few years including the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic.

France has a centralized system of schooling for its 13 million students. A Ministry of Education establishes the curriculum for all levels of schooling and allocates both staff and funds to the 31 regions or academies headed by a rectuerresponsible to the national Ministry of Education.

The historically high degree of uniformity in curriculum and instruction has lessened in recent years as the Ministry of Education has delegated to local regions, curricular discretion. Moreover, local variation in schooling and classroom lessons–Brittany in the northeast of France and Marseilles on the Mediterranean Sea–Inescapably exists.

In France, education is compulsory for children between the ages of three and 16 and consists of four levels:

- Preschool (écoles maternelles) – ages three to six

- Primary school (école élémentaire) – ages six to 11

- Middle school (collège) – ages 11 to 15

- High school (lycée) – ages 15 to 18

Students are required to attend school from age six to sixteen. All schooling between kindergarten and university is free except for private schools where parents pay fees. Seventeen percent of French children attend private schools.

Schools open in September and end in June with two weeks of vacation every few months. Also, most French schools are open Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday. Wednesdays are often a half-day. The school day usually runs from eight AM to four PM. French students usually have over an hour for lunch and many go home to eat.

Class sizes in public schools vary. For instance, in primary grades, one teacher and a teaching assistant typically will be in charge of 25 children; in secondary school, teachers commonly have 30 or more students.

Even with these similar features, there are differences in schooling across France (e.g., urban/rural, small/large schools, heavily immigrant/mostly middle and upper middle class, public/private). Thus, what some authorities call a “typical” lesson may simply be what they believe (or want to believe) is a common instance of classroom teaching. Readers should keep that in mind.

Here are a few photos of “typical” elementary and secondary classrooms in France.