In this week’s post, Jordan Corson shares some of the experiences and research with “youth on the move” that are captured in his latest book, Reconceptualizing Education for Newcomer Students (Teachers College Press, 2023). Corson is an assistant professor of education and affiliated faculty member of the M.A. in Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Stockton University. He is also a co-author with Thomas Hatch and Sarah Gerth van den Berg of The Education We Need for a Future We Can’t Predict (Corwin, 2021). Corson’s previous posts include: Who and What Counts in Education? A Conversation with Jordan Corson. A previous version of this post appeared on the Teachers College Press Blog.

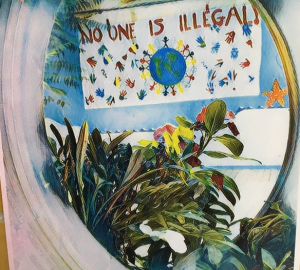

As schools tell it, the history of immigration and schooling in the U.S. is a story of two paths: exclusion or assimilation. From the 19th century and early 20th century to present day, schools have commonly operated as places of oppression for immigrant students. Success—or perhaps educational survival—here depends on a capacity to conform to inherently oppressive structures. In beautiful instances, though, schools can realize the dream of making public, democratic places that serve communities. That cherish students’ voices. That nurture and care, making schools a welcoming refuge. That provoke intellectual curiosity bound up in dynamic linguistic and cultural practices. Such places center students’ identities. Joy bursts from their walls. Here, language is not something to acquire but something to do. Even as students struggle, these schools find ways of better including youth and helping them succeed.

Schools can realize the dream of making public, democratic places that serve communities. That cherish students’ voices. That nurture and care, making schools a welcoming refuge. That provoke intellectual curiosity bound up in dynamic linguistic and cultural practices.

For youth “on the move” – a term that highlights the importance of rethinking migration, nationality, and the borders we researchers and policymakers place on immigrant youth — this kind of educational structure can be found in newcomer schools. Newcomer schools are a model of public school specifically designed to affirm the linguistic and cultural identities of youth on the move who have recently arrived to a new place. In recent years, researchers and educators have attended to and championed this school model as one of educational possibility.

This kind of cherished educational environment sits at the center of my book, Reconceptualizing Education for Newcomer Students: Valuing Learning Experiences Inside and Outside of School. Building on the work of scholars and educators like Monish Bajaj, Daniel Walsh, Lesley Bartlett, and Gabriela Martínez aims to champion affirmative forms of schooling and to show the powerful educational possibilities born of supporting youth on the move. At the same time, though, the questions I pose, wander from asking how schools might improve or how school systems might better include youth on the move to ask: Why are youth on the move considered educational “problems” in the first place? Why have policymakers and researchers historically framed kids, especially those from marginalized communities, as “problems” for schools to solve? Why has the solution been to make of school a rigidly bordered place where students “access” education? Along with these questions about youth on the move in schools, I also explore educational life beyond the boundaries of schooling.

Why are youth on the move considered educational “problems” in the first place? Why have policymakers and researchers historically framed kids, especially those from marginalized communities, as “problems” for schools to solve?

To explore these questions, I look at the history of immigration and schooling in New York City. Beyond the mountainous history of oppressive education, a history of including and “solving the problem” of educating youth on the move shows the way education systems have made sense of youth on the move and created different systems to include them with the “melting pot” or “kaleidoscope” of the United States. This history is also bundled up in critiquing how school has both come to be a place of borders and have a monopoly on education. I explore these histories from an institutional perspective, but histories of communities building schools, demanding policy changes, and challenging oppressive orders puncture a smooth, institutional narrative.

Along with this historical inquiry, I veer from school entirely by presenting an ethnographic study of education in everyday life with nine youth from a newcomer school in New York City. Even in culturally and linguistically affirmative schools, youth still become marginalized, labeled “at-risk” of dropping out, and their educational lives become defined by what happens in school. Of course, education is always happening. Learning, creating, and figuring out the world happen outside of school and often without school as a reference point. Therefore, I asked: What might happen if we moved with youth into everyday life, leaving behind the language and logics of school? Instead of thinking about something like academic outcomes, what if we studied within everyday educational practices themselves? What if the only understanding of learning was the pleasure experienced in the learning process?

What might happen if we moved with youth into everyday life, leaving behind the language and logics of school? Instead of thinking about something like academic outcomes, what if we studied within everyday educational practices themselves?

To that end, I spent a year with the youth who participated in this project, hanging out in school, clubs, and museums. We wandered New York City, riding subways, exploring parks, checking out summer basketball games, or chatting in cafes. Whether inside of school or outside of school, youth and I explored wondrous educations that were not concerned with school or dominant systems. They lost themselves in memory as they described learning photography in the Dominican Republic. Or, they navigated their own form of language education while creating plurilingual rap lyrics. Youth participants asked themselves and each other what kind of people they wanted to become and what they owed each other. Education is not, as they regularly demonstrated, something concerned with access or outcomes, but about living and changing the world.

I started research for this book in the middle of the Trump presidency. Even in the “sanctuary” of New York City, danger permeated every corner of everyday educational life. As much as this project was filled with laughter and play, the carceral systems that define the U.S. made it dangerous for youth participants to simply learn or express themselves in public places. A few years later, U.S. policy and xenophobic action entwine and continue along an infuriatingly predictable trajectory. The current “migrant crisis” is only the latest moment in a long history of a country that chooses to impose violent borders, think of people on the move as “problems,” and considers education through this same bordering logic.

Understanding these relentless issues, I hope to contribute to the kinds of work that center youth voices and challenge deficit narratives that overwhelm conversations about immigration and immigration. Moreover, I hope to does so in a way that does not bolster educational research or school systems but disrupts them at their very roots. Youth on the move should not have to prove that they deserve to belong to schools or any other institution in the U.S. As one participant told me, “I should get these things because I’m a human.” Instead, researchers and policymakers should question the borders we have made in schools and elsewhere.