This week, IEN continues its scan of news and research on tutoring as a “learning loss” recovery strategy. The second part of this three-part series focuses specifically on what’s being written about the challenges and opportunities for carrying out tutoring strategies effectively on a large scale. Part 1 of this series described some of the funding initiatives contributing to the emphasis on “high-dosage” tutoring as a “recovery” strategy, as well as some of the initiatives to expand access to tutoring being pursued in the US in particular. Part 3 will survey some of the specific new developments and “micro-innovations” that could make tutoring more effective in the future. This series is part of IEN’s ongoing coverage of what is and is not changing in schools and education following the school closures of the pandemic. For more from the series, see “What can change in schools after the pandemic?” and “We will now resume our regular programming.” For IEN’s previous coverage of news and research on tutoring, see Scanning the News on High Dosage Tutoring, Part 1: A Solution to Pandemic Learning Recovery, and Part 2: Initiatives and Implementation So Far. This post was written by Jonathan Beltran Alvarado and Thomas Hatch.

Although it will take years to judge the full effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on students, it’s already possible to track – and in some cases predict – the challenges that large-scale “recovery” initiatives like expanding access to tutoring are likely to encounter. Those analyses depend on the answers to several critical questions, including:

- To what extent do the goals of the initiative meet the needs of the people involved?

- To what extent do the capacity demands for funds, personnel, time, and other resources match the existing capabilities?

- To what extent do the values reflected in the initiatives mesh with the values of the people, organizations, and communities where those initiatives are supposed to take off?

Both the goals and values of many tutoring initiatives match what many policymakers, funders, educators, and families perceive as an urgent need for strategies that focus directly on improving students’ learning, particularly as measured by test scores (as detailed in the first post in this series “Tutoring takes off – Scanning the news on the emergence of tutoring programs as a strategy to combat “learning loss (Part 1).” However, even with a fit between goals, needs, and values, the extent to which different schools, districts, and communities have the capacity to pursue effective tutoring interventions on a large scale remains in question. In order to get a better sense of the capacity challenges that schools may be facing in pursuing tutoring initiatives, three issues are particularly relevant:

- What kind of tutoring are students getting?

- Who is actually getting tutoring support?

- What are the challenges of scaling up tutoring interventions?

What kind of tutoring are students getting?

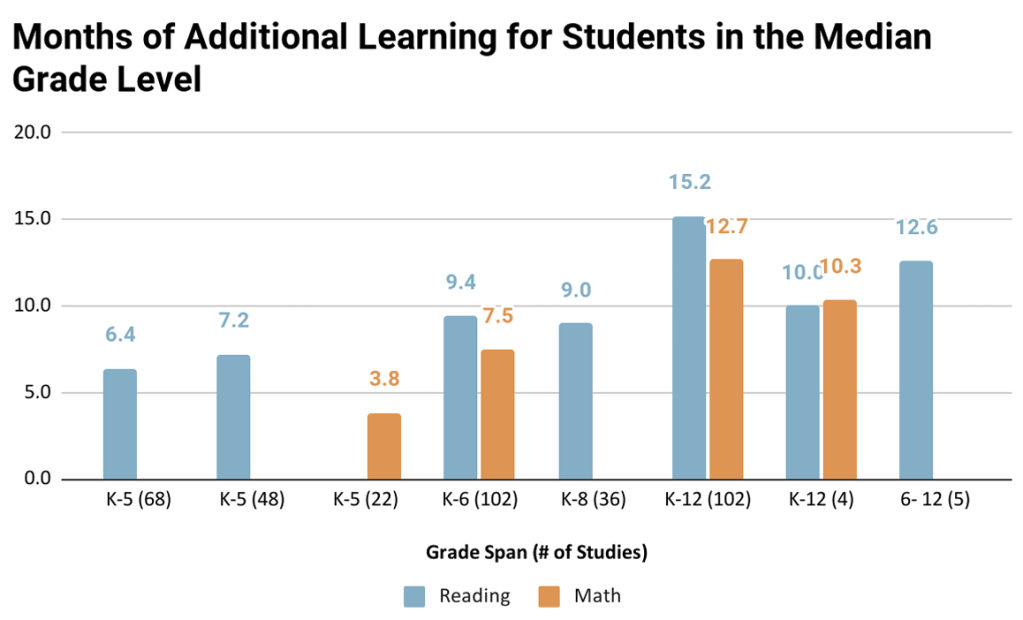

Research, including eight different meta-analyses, make clear that tutoring can have a significant positive effect on student learning. For example, a systematic review of 89 tutoring programs and related field experiments shows that “tutoring programs yield consistently substantial positive impacts on learning.” There is even evidence that, under some circumstances, online tutoring programs can be effective.

“Eight meta-analyses including over 150 studies consistently find that tutoring results in substantial additional learning for students,” High-Impact Tutoring: An Equitable, Proven Approach to Address Pandemic Learning Loss and Accelerate Learning, National Student Support Accelerator

However, tutoring interventions vary in key programmatic components, such as the type of tutor, their curriculum characteristics, their mode of delivery, and their frequency and duration, and a number of studies show that not all these variations are equally effective. As Tennessee Education Commissioner Penny Schwinn put it, “There is a general misunderstanding that you can just find a body, put them in a classroom, and anybody can tutor.”

“There is a general misunderstanding that you can just find a body, put them in a classroom, and anybody can tutor.” – Penny Schwinn, quoted in Despite Urgency, New National Tutoring Effort Could Take 6 Months to Ramp Up

Among the many options, high-impact or high-dosage tutoring is regarded as the most effective form of student support. As the US Department of Education sums it up, the key features of high-dosage tutoring include:

- Duration of at least 30 minutes

- Frequency of three or more times per week

- One-on-one or small group instruction

- Alignment with an evidence-based curriculum or program

- Providers who are educators or well-trained tutors

Consistent with this definition, research suggest that the most effective tutors are teachers and paraprofessionals who are invested in relationship-building and well-informed in the content rather than volunteers; tutors benefit from having high-quality materials aligned with the state’s standards, which should be easy to use by tutors and students; and the best results occur when high-impact tutoring is embedded in schools, preferably taking place during school or immediately before or after the school day, making it easier for students to attend.

Who is actually getting tutored?

Despite the considerable agreement about the impact of high-dosage tutoring, many students are not participating in it. For example, a survey by the EdWeek Research Center in 2021 found that 97% of US district leaders surveyed said they were or would be offering tutoring to about one-third of their students (equal to about 17 million of the 51 million K-12 students in the US). However, data from the Department of Education for the 2022-2023 school year shows that while 83% of schools reported offering some form of tutoring only 37% of schools provided high-dosage tutoring, and only 30% of their students received it.

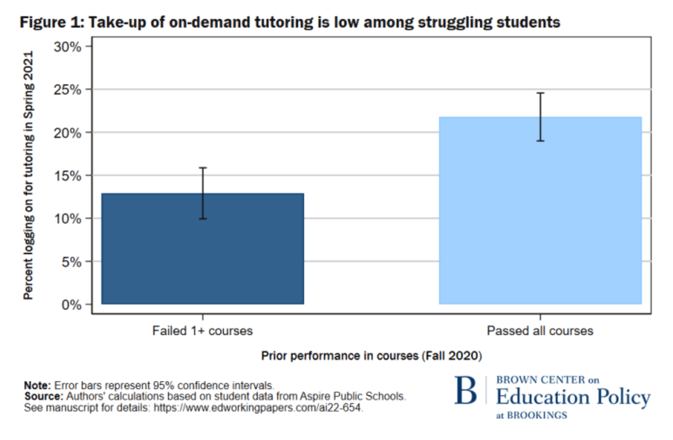

Evidence also suggests that many students are not even taking advantage of the “on-demand” tutoring programs that are supposed to be easier for them to access. For example, a study of an “on-demand” tutoring system implemented in a network of charter schools in the spring of 2021 showed that only 19% of students ever accessed the program, and struggling students were even less likely to opt in than their higher-achieving peers, with a take-up rate of 12% against 23% respectively. An intervention involving extensive communication via mail, email, and text messages with students and families increased participation substantially, but only about one-quarter of students ever logged on to the tutoring platform.

The good and bad of virtual on-demand tutoring, Brookings

As a result, the study’s authors concluded: “The availability of tutoring rarely translated into the use of tutoring. This open-access program is unlikely to have reduced—and may, in fact, have increased—inequalities in students’ academic experiences and outcomes.”

“The availability of tutoring rarely translated into the use of tutoring. This open-access program is unlikely to have reduced—and may, in fact, have increased—inequalities in students’ academic experiences and outcomes.” — Susanna Loeb & Carly D. Robinson, “The good and bad of virtual on-demand tutoring”

Evidence of fast-growing remote tutoring approaches developed by companies like Paper and Varsity Tutors are also having trouble getting students to opt-in to their services. Varsity Tutors, for example, markets its services as a newer, more scalable tutoring model in which schools pay a subscription fee for each student. That subscription gives students access to an online platform where they can post a problem and get connected to an available tutor. Without using the camera or the microphone, a designated tutor can solve the problem by sharing the screen, uploading photos and documents, or typing in a text box.

Despite the ease of use, the persistent low take-up rates have disappointed many school districts and altered the demand for opt-in remote tutoring. Santa Ana Unified, California, invested over $1.1 million to provide access to 41,000 students, but just 1,000 logged from December 2021 to May. In Columbus, Ohio, district data confirmed that only 7% of students received opt-in tutoring through Paper’s platform, which dissuaded them from renewing the $913,000 contract signed in 2022. Fairfax County, Virginia, recorded an even less impressive take-up rate of only 1.6 percent of students accessing the platform Tutor.com. What is worse, recent testimonies and investigations are shedding light on the frantic business dynamics of companies like Paper, which has a monetary incentive to make a tutor responsible for more students than it can meaningfully manage or teach subjects they don’t know well.

School leaders are facing this situation by changing the contract incentives and demanding more accountability from remote tutoring companies. In an interview with the Hechinger Report, Terry Grier, former superintendent of Houston, said it was “immoral” for schools to sign “blank contracts” without strings attached. He said he tried online tutoring, but it didn’t work well. “Kids wouldn’t use it,” Grier said.

“It is ‘immoral’ for schools to sign ‘blank contracts’ without strings attached.” — Terry Grier quoted in “Proof Points: Many schools are buying on-demand tutoring but a study finds that few students are using it”

To address these issues, some school districts have designed contracts that promote vendor accountability. Ector County, Texas, developed a pilot of outcomes-based tutoring contracts in 2020 before the pandemic. The school leaders scaled up the model over the summer of 2020, recognizing that academic recovery would require a significant investment. Their goal was to provide intensive virtual tutoring to 6,000 students under a contract, tying the vendor’s revenue to the rate of learning growth on the NWEA MAP assessment administered three times during the school year.

Still, districts are paying significant sums to on-demand tutoring programs that may not be as cost-effective as they look. A Hechinger Report article explains that Varsity Tutors charges a flat fee of $40 to $80 per student (depending on school district size). This price may look attractive compared to resource-intensive high-dosage tutoring programs that cost roughly $4,000 per student yearly. However, if a 10,000-student district buys a remote tutoring program for $800,000, an average take-up rate of 20% elevates the cost per student from $80 to $400. Furthermore, the students who participate in these programs tend to be high achieving students rather than the low achieving students for whom the program was intended.

What barriers to providing effective tutoring need to be addressed?

Along with the challenges of engaging students, high dosage tutoring is a resource-intensive strategy and costs and scalability remain big concerns. As a recent meta-analysis concluded, optimizing quality without increasing costs serves as a key challenge for policymakers. Furthermore, school districts across the US have been scrambling to find effective teachers – much less tutors – because of the difficult conditions and burnout endured by educators post-pandemic. The shortage of teachers means that some tutoring plans have had to scale back significantly, with one study of mid- to large-sized school districts across 10 states in 2021 showing that some districts that had planned to offer 90 tutoring sessions ended up offering 13 sessions throughout the year. The tight labor markets may also prevent some districts, particularly those with fewer resources available, from providing tutoring from the teachers who could be most effective. Not surprisingly, some districts have turned to cheaper substitutes, which partly explains the popularity of remote opt-in tutoring platforms.

Discrepancies in how the schools provide tutoring, low student and parental engagement, and lack of technological resources have also diminished the impact of online tutoring. Thus, when remote tutoring options are available, the youngest students face a steeper learning curve as they spend additional time learning how to navigate the interactive platform that connects tutors and students. On top of that, the need for high-speed internet means that students living in rural areas with low parental support or lacking Wi-Fi have additional barriers to receiving academic assistance. Consequently, even the most easily scalable remote tutoring options may not reach many of the students and districts who need the most support, reinforcing existing inequalities.

Next steps?

Tutoring alone cannot address the many issues that make it difficult to improve learning at scale for all students, and an overreliance on tutoring can take time and attention away from needed investments in support for student wellbeing and other aspects of their development. But, taken together, the latest news and research on high-dosage tutoring in the US both confirms that it is one of the most promising strategies for improving students’ academic performance in areas like reading and math and demonstrates that it is also very difficult to put into practice at scale.

[T]he latest news and research on high-dosage tutoring in the US both confirms that it is one of the most promising strategies for improving students’ academic performance in areas like reading and math and demonstrates that it is also very difficult to put into practice at scale.

As an Aspen Institute report puts it, tutoring may be one of the best ways “to teach anyone anything,” but scaling tutoring programs will continue to be challenging given limited money and a limited labor supply of tutors on top of the difficulties of modifying school’s “standard operating procedures” to find time in school schedules to incorporate tutoring and to get students to participate on a regular basis. Adding to the challenges, as federal COVID relief funding ends, many states, like Tennessee, Connecticut, and Texas, are scrambling to find new ways of financing their tutoring efforts. Under these conditions, it is easy to predict that the surge in popularity of tutoring programs will subside without some progress in addressing the high costs, significant demands and capacity problems that come along with high-dosage tutoring.

Still to come: “Promising innovations? Scanning the news on the emergence of tutoring programs after the school closures”.