In this 2-part interview, Hirokazu Yokota provides an inside look at a municipality-led educational reform effort in Japan. In the first part, he describes the background and key elements of the initiative from his perspective as deputy superintendent and director for education policy at the Toda City Board of Education. The second part of the interview will focus on what he’s learned from his experience with the initiative as he returns in April to his regular posting as a government officer at the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Mr. Yokota has previously written about his experiences as a parent and educator during the pandemic (A view from Japan: Hirokazu Yokota on school closures and the pandemic) and his work as a policymaker and government officer at Japan’s Digital Agency (A view from Japan (part 2): Hiro Yokota on parenting, education and the new Digital Agency in Japan). The graphics included in these posts are drawn from a slide show on Education Reform in Toda City. For further information on the Today City reforms see the slide show or contact Hiro via Linkedin.

IEN: At the time of your previous post, you were working at the newly established Digital Agency, government of Japan. What brought you to Toda City?

Hirokazu Yokota: As I mentioned in the first post, I am a government officer at the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. At a certain point in our career, most of the Ministry officers are delegated to local governments to better bridge policy and practice. The term usually varies from two to three years, and after returning to the Ministry they are supposed to further polish their policy making and implementation skills with more knowledge of what’s occurring at the ground. Although most of my colleagues have been delegated to prefectural BOEs, I’m currently serving as a deputy superintendent and director for education policy at Toda City BOE – a municipality in Saitama prefecture (20 minutes from the Tokyo metropolitan area by train, Toda City has 12 elementary and 6 junior high schools with some 12,000 students.

IEN: What’s the issue you have been working on?

Hirokazu Yokota: I’m basically trying to change the “grammar of schooling” – you can see what one of our schools is doing in the video “Creating Your Future @ STEAM Lab”. As we talked about in in your class on School Change and you address in your last book “The Education We Need for a Future We Can’t Predict,” it’s disappointingly difficult to transform the “technical core” – classroom instruction – of schooling, and most of the times micro-innovations, rather than reforms targeted at the entire school systems, take place in ecological “niches.” In Japan, one device per student was distributed with the subsidy from the Ministry to all the students in elementary and junior high schools during Covid-19. However, there is still too much pressure on one-way, teacher-led classroom instruction throughout this country, and I’m personally afraid this new and powerful ICT tool is not as utilized at schools as initially expected.

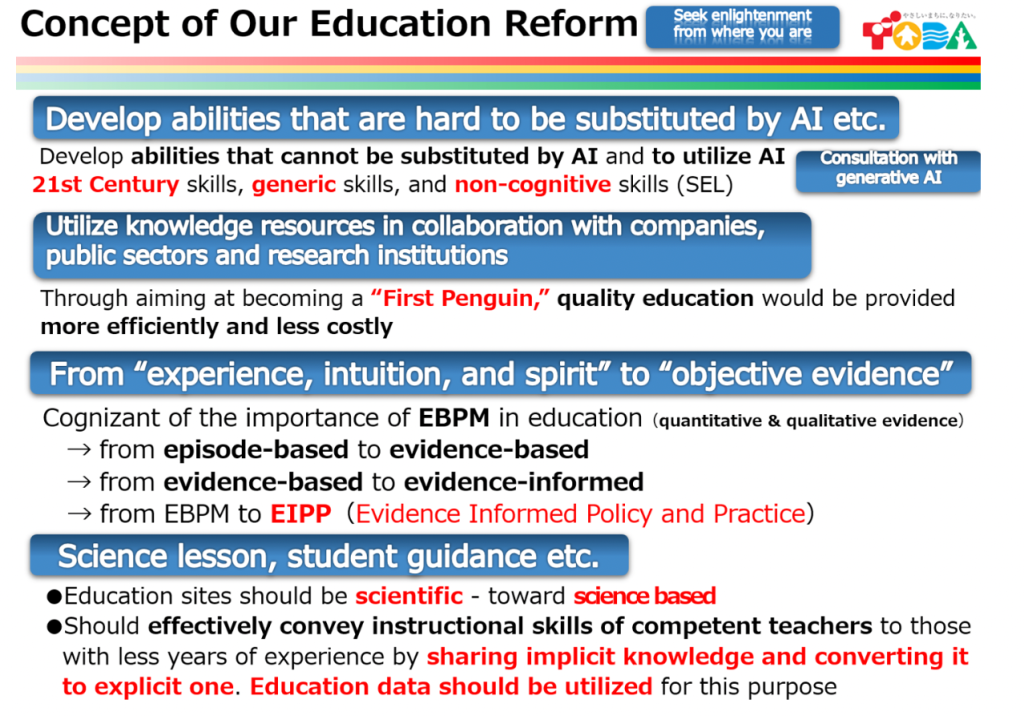

In this regard, Toda City is an exception as you can see from the STEAM video. The turning point was when Tsutomu Togasaki, a former school principal, assumed superintendency in 2015. Back then, he articulated four concepts of education reform; (1) develop abilities that are hard to be substituted by AI, (2) utilize knowledge resources in collaboration with companies, public sectors and research institutions, (3) get away from education that solely relies on“experience, intuition, and spirit” and focus on “objective evidence,” and (4) utilize educational data so that instruction/student guidance etc. will be based on evidence that is corroborated by research.

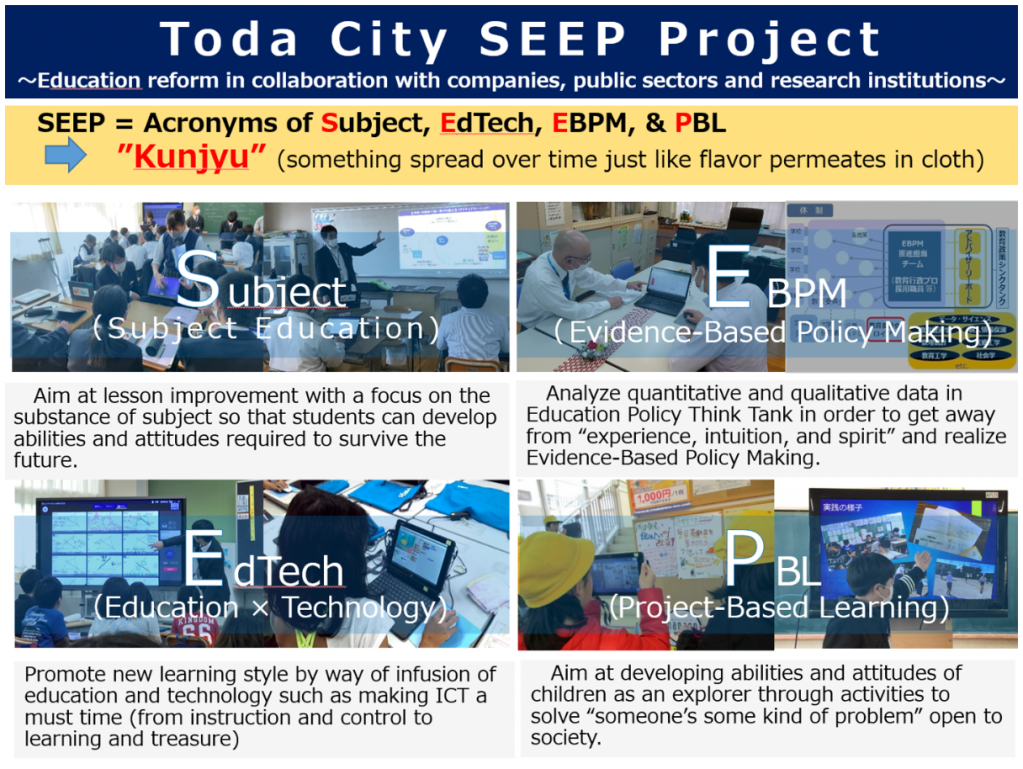

In order to realize this vision, we’ve implemented the Toda City SEEP Project composed of Subject (subject education), Edtech, EBPM (evidence-based policy making), and PBL (project-based learning). And it’s my primary responsibility now to move this ambitious reform into the next phase while narrowing the gap between policy and practice and building the capacity for educators.

IEN: What do you think are the root causes of this problem?

Hirokazu Yokota: Changing the status quo is always an uncomfortable step. In the context of Japan, which is a relatively high performer in PISA and TIMSS, some educators regard aggressive education reforms such as ours as something that may undermine their past success. At the outset of our reform in Toda City (8 years ago), the superintendent found that there was a lot of pushback from school principals and others. Even the city council members, who were generally pro-reform, had some resistance to what they saw as his “radical” vision.

Undeterred, Mr. Togasaki continued to say that “in order to bring the movement of the ever-changing society into the classroom, BOE prepares raw materials for a variety of learning and human resources. Schools are expected to make the most of them for lesson improvement, in-school PD, and workshops”. He even went on to say it is extremely insincere (for educators) not to try to understand the society where students will dive into after graduation from school, and we should make school a learning place where children can feel the future. “Avoiding risks is the greatest risk, “ he warned, and he welcomed an ambitious challenge (even if it is 60 points out of 100) rather than a mediocre practice (that is 90 points). These are the words now I can hear from principals and other school staff, which means the superintendent’s vision has permeated into the ground over the eight years.

“we should make school a learning place where children can feel the future. ‘Avoiding risks is the greatest risk,’ he warned, and he welcomed an ambitious challenge (even if it is 60 points out of 100) rather than a mediocre practice (that is 90 points).” – Tsutomu Togasaki, Superintendent of Toda City

There were two important policy levers that have supported this reform. The first is the ICT device distribution through the GIGA School Initiative. We had a clear intention to use this new tool for the purpose of transforming teacher-led instruction into student-centered learning. Additionally, in contrast with other municipalities that said “let young teachers use ICT first,” we started with veteran teachers, knowing that the use of ICT will spread throughout the school much faster once they see veteran teachers, with solid instructional design, use ICT effectively. This strategy worked out very well.

The second was unexpectedly COVID-19. It attacked our city exactly when we started to implement PBL. However, it did not slow down, and actually accelerated PBL. Since students could not do what they took for granted – from school excursion to learning face-to-face with classmates and teachers -, they, with a sense of urgency and ownership, started to engage in problem-solving by themselves. For example, since students could not go on a school trip, they made project mapping on the wall of the gymnasium at their school in order to experience a campfire (as if they were actually on a trip site). Additionally, in order to make PBL an authentic learning experience, ICT is an indispensable tool – from creating presentation slides together to conducting a questionnaire to getting feedback from outsiders online.

IEN: With these policy reforms already in place, what did you do first to tackle the problem?

Hirokazu Yokota: I started out by listening to educators here – visiting schools one by one and meeting principals, head teachers etc. where they are. Through these candid conversations, although I was building future policy directions – study (1) lesson, (2) student guidance, and (3) class/school management scientifically (which is directly related to my former task at the Digital Agency that I described in my last blog post, the Roadmap on the Utilization of Data in Education ), I had a feeling that educators on the ground are still in the stage of utilizing ICT and not necessarily ready for a next step of utilizing data from there.

For the first direction (study lesson scientifically), we sought to promote data-driven lesson study toward the realization of proactive, interactive, and deep learning, as is stipulated in the new national curriculum standard (Courses of Study). Therefore, as a common language to transform teacher-led instruction into student-centered instruction, we shared with schools the Toda City Version SAMR model.

Although all the schools were in the Substitution or Augmentation Phase back then, the timing and specific tools of students using ICT was still controlled by the teacher. By letting go of control and giving students the handle of learning, we can move onto the Modification Phase, which is the first step of changing the “grammar of schooling.” Whenever I visited classrooms, I used this model as something like the Danielson Rubric for classroom instruction, not to evaluate teachers but to have an understanding of where we are and clarify room for lesson improvement.

IEN: What challenges did you encounter?

Hirokazu Yokota: Regarding the aforementioned three future policy directions, there were few policies in place for the second (study student guidance scientifically) and third (study class/school management scientifically). And actually, I noticed that teachers have a fear of being evaluated when we implement the first direction (make lessons etc. evidence-based). On the other hand, I noticed that because absenteeism, especially for elementary school students, has been increasing rapidly, detecting early signs of absenteeism by data utilization is actually in greater need for educators (second direction). Moreover, although school leadership is indispensable for these policy reforms, we did not have a common language – lenses or perspectives – to reflect on school management (third direction). So there was definitely a great deal of policy need in these two directions, which urged me to create new reforms in order to realize “an education where nobody will be left behind.”

IEN: What changes did you make?

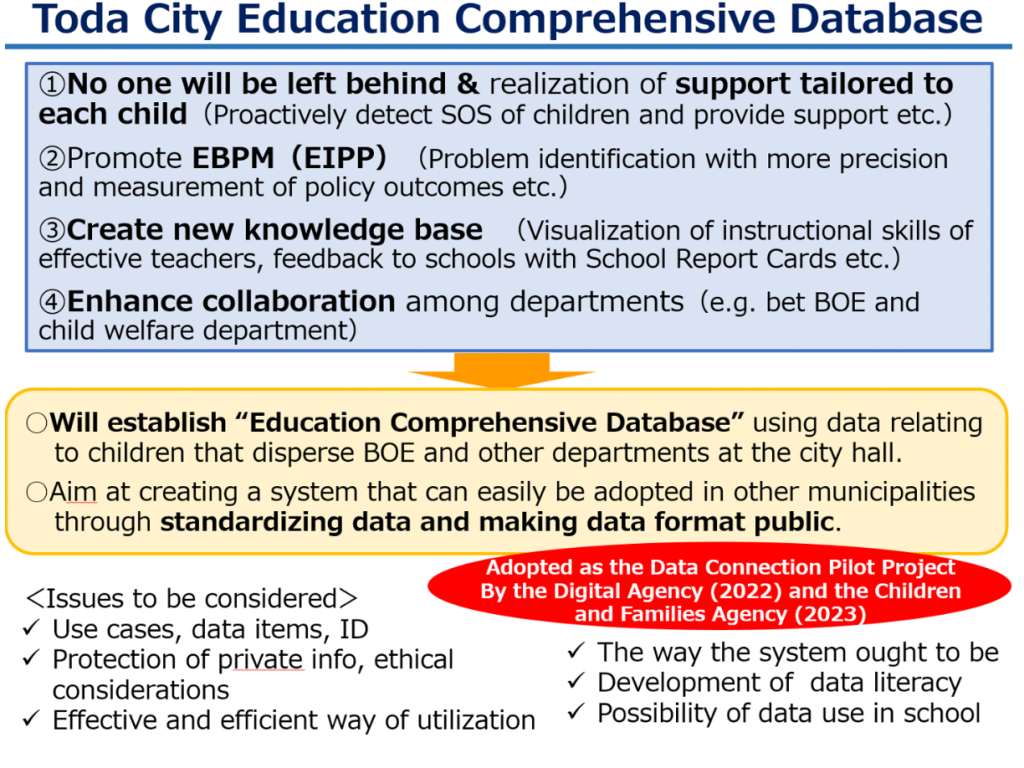

Hirokazu Yokota: For the second direction of studying student guidance scientifically, I started a new initiative to establish the Education Comprehensive Database that will consolidate data related to children from the BOE and other departments at the city hall. Essentially, we are asking are there any signs of absenteeism, bullying etc. that appear in advance, that we could address? Our main hypothesis here is that, if we connect and analyze a variety of data relating to children, we might be able to detect early indicators of absenteeism and provide support accordingly. The number of absentees has been increasing nationally for ten years in a row, and just hit a record high of some 299,048 (22.1% increase from the previous year). This upward trend is similar in our city, with the number of absentees in elementary school increasing rapidly, but our hope is that this database will serve as something like the Early Warning Indicator Systems in US schools.

Establishing such a database is very laborious, including deciding on which data to use, arranging ID’s for all the data, considering ways to collect and store the data (including digitization of paper information), and devising protective measures for private information, access control, and ethical guidelines. In collaboration with private companies, we are now coming close to completion and moving into the phase of actually using this database with schools.

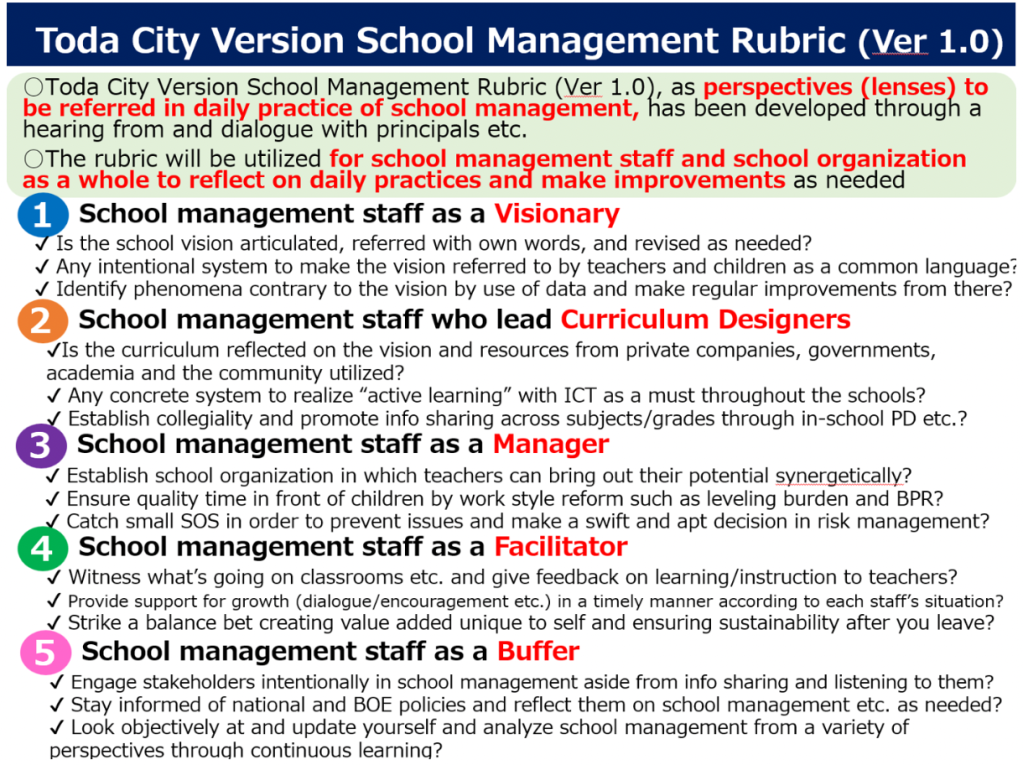

For the third direction of studying class/school management scientifically, based on the discussion with principals, head teachers and others over some 40 hours, I drafted the Toda City Version School Management Rubric. I believe that our city is the first in Japan to publish such a rubric. Our basic concept here is to provide feedback on school management just like providing feedback on classroom instruction for continuous improvement. As you can see from the slide below, each element of this rubric is verbalized as “a challenging goal” – to be accomplished if and only if school management staff make concerted and intentional efforts over the time. For example, although most of the schools articulate their school visions, there are few schools that have intentional systems to make the vision referred to by teachers and children a common language (No.1 – school management staff as a visionary). Additionally, there are some teachers who engage in transformational practices in every school, but spreading this “good practice” throughout the school is extremely difficult (No.2 – school management staff who lead curriculum designers). With this rubric, the BOE and school management staff have common ground to talk about where we are, what we are doing and what we are not, and what we can do together for further improvement.

To be continued in “Hiro Yokota on aggressive education reforms to change the ‘grammar of schooling’ in Toda City (part 2)

Pingback: Hirokazu Yokota on aggressive education reforms to change the “grammar of schooling” in Toda City (part 2) | International Education News

Pingback: Hirokazu Yokota on aggressive education reforms to change the “grammar of schooling” in Toda City (part 2) - Education