In the second part of this 2-part interview, Hirokazu Yokota shares what he’s learned from his experience working on a municipality-led educational reform effort in Japan. In the first part of the interview, Yokota describes the background and key elements of the reform effort from his perspective as deputy superintendent and director for education policy at the Toda City Board of Education. In April, Yokota will return to his regular posting as a government officer at the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Yokota has previously written about his experiences as a parent and educator during the pandemic (A view from Japan: Hirokazu Yokota on school closures and the pandemic) and his work as a policymaker and government officer at Japan’s Digital Agency (A view from Japan (part 2): Hiro Yokota on parenting, education and the new Digital Agency in Japan). The graphics included in these posts are drawn from a slide show on Education Reform in Toda City. For further information on the Today City reforms see the slide show or contact Hiro via Linkedin.

IEN: In the first part of our interview, you talked about the goals and key elements of the Toda City education reforms, but can you tell us a bit about what you learned in the process?

Hirokazu Yokota: Through dialogues with educators in Toda City, I learned that they have a mixed feeling toward this aggressive education reform. Although change is necessary, some might regard it as the negation of their past – sometimes successful – practices. That reminds me of the PISA shock around 2003; when Japan’s ranking substantially fell in the midst of the implementation of a child-centered learning reform, and the addition of a significant amount of learning content with the revision of the Courses of Study (national curriculum standard). Rather than throwing away past things altogether, we should not forget the spirit of “continue past things and pioneer the future while developing them.”

For example, whether it’s ICT education or generative AI or anything new, teachers will not change their practices no matter how many times they are told by Boards of Educations or principals until they understand it’s necessary and beneficial to them. Therefore, we put so much effort into letting teachers actually use ICT in professional development opportunities and experience the merit of it. Then, they became strong promoters.

Whether it’s ICT education or generative AI or anything new, teachers will not change their practices no matter how many times they are told by BOEs or principals until they understand it’s necessary and beneficial to them.

Another important thing was that because there are more and more young teachers who tend to lack a common foundation for teaching and learning, we were faced with the need to re-emphasize the Subject Education (“S” of our SEEP Project). That’s why we created the Plan for Strengthening Subject Education in May 2023. The key concept here is that student learning is analogous to teacher learning. So, in order to realize individually optimized and collaborative learning for students, we, through professional development and other means, need to provide these learning opportunities for teachers.

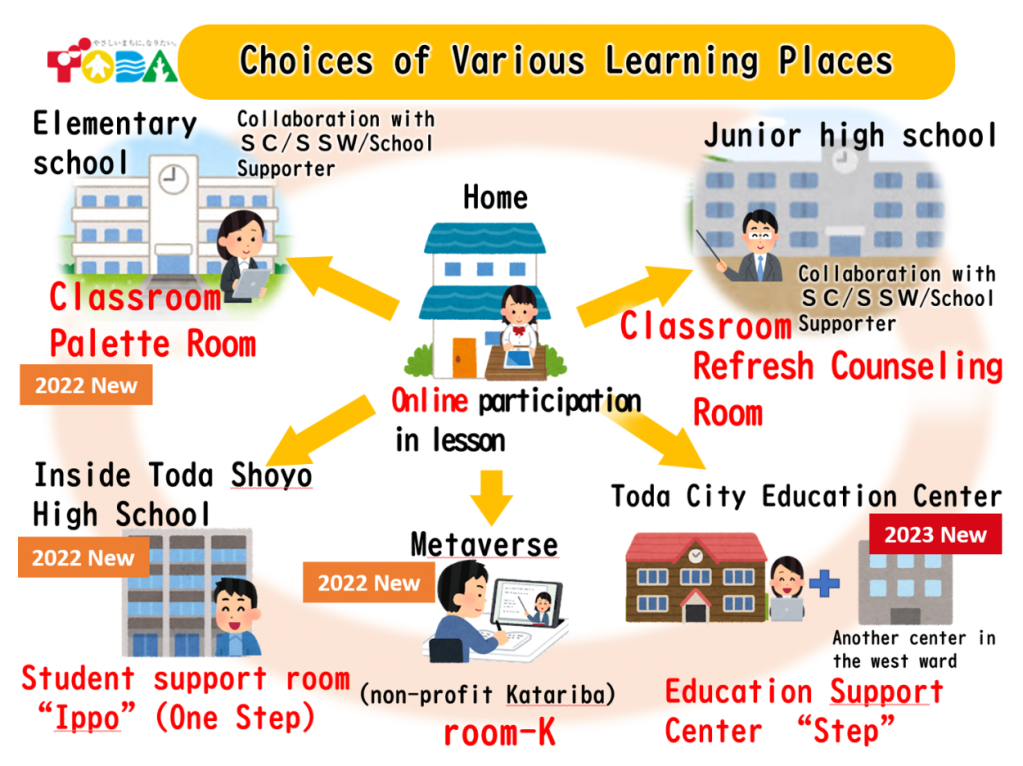

The last big issue is absenteeism. The figures released last October show we hit a record high of 299,048 – with a remarkable increase of 22.1% from the previous year. In order to tackle this problem, in March 2022, we published the Toda-Version Alternative Plan, which aims at an education where nobody will be left behind. What we’re essentially doing is to prepare choices of various learning places. In the last fiscal year, because the number of absentees at the elementary level has been rapidly increasing, we set up in-school support rooms (“Palette Room”) in all the 12 elementary schools for students who are experiencing challenges in the classroom. Depending on their situation, they can choose to participate in classroom lessons virtually from the Palette Room or physically during the day. Also, when some students cannot stay in their classroom due to their developmental issues, they can visit the Palette Room to cool themselves down before returning to their classroom. I also saw an immigrant student, who cannot understand Japanese well, spend some time at the Palette Room to receive one-on-one instruction for a few months, and after then they can keep up with classroom lessons and stop using the Palette Room. In short, students, in consultation with teachers, have the freedom to use this room whenever it fits for them.

Additionally, we expanded our education center and established a student support room that accommodates junior high school students in a high school. Furthermore, with the help of a non-profit, we also set up an online education center in the metaverse for children who mostly stay at home and cannot go outside. Our policy measures are unparalleled to any municipal BOE in Japan, and have gotten a lot of attention from the media (including in Forbes, NHK News Web, and the MEXT website).

IEN: What advice do you have for others who might want to pursue a similar approach, whether in Japan or other parts of the world?

Hirokazu Yokota: I understand that it is very, very difficult to change others. In order to make transformational change in education for students, we should be mindful that change must start with us adults. The typical relationship between the BOE and schools is resistant to these changes, with the board urging schools to make visible changes while educators in schools are fed up with new things imposed from above. We as a BOE wanted to change this image. Thus, the BOE changed first by going outside of the education circle and bringing new movements of the society into our office. This is because in order to implement our SEEP project (as is mentioned in the last post), there is no way but to collaborate with private companies, public sectors and research institutions. At the beginning, BOE officers stopped trying to provide all the contents by themselves, collected raw materials in collaboration with outsiders, “cooked” with these, and then, in a sense, provided schools with the “cuisine” (e.g. BOE reached out to private companies that have contents of programming education, created a curriculum in collaboration with them, and implement it in schools). Gradually, as principals understood that they can do these new things without being threatened, schools became cooks themselves with raw materials provided by the BOE (e.g. schools adjusted their annual curriculum plan so that they can provide programming education in a more coherent way). In this way, principals gradually began to see the benefits and started to change themselves, then this change also spread out to teachers and finally classrooms. Although one teacher can change his or her practice, when it comes to systemic change, I don’t think the transformation comes from the right to the left. It should happen the other way around – BOEs should change first. Additionally, I’m sometimes surprised by the fact that schools, in addition to being cooks, even prepare raw materials by themselves (e.g. some schools reach out to outside experts on programming education without BOE’s involvement, and invite them to their in-school professional development session) . Because there are so many “cooks” in the education governance, which means each stakeholder tries to intervene in school reform in an incoherent way, our approach of giving autonomy to schools while providing support is indispensable.

In addition, what makes education policy complicated is its governance system. Also in Japan, there are many reformists who say “Our schools are broken. Let’s fix it.” However, as there are more and more cooks in the kitchen, making coherent and sustainable policies becomes more challenging. That’s why we as a BOE have so much respect for school principals and give them considerable autonomy so that they, with the deepest understanding of individual students, can be engaged in school reform themselves. I believe that school can be reformed only from within and truly important education reforms should happen from schools, not from MOE or BOEs. In order to realize that, management by BOE should shift from “one-size-fits-all control” to “individual support” and BOEs should be institutions that accompany schools and support their self-propulsion.

School can be reformed only from within, and truly important education reforms should happen from schools, not from MOE or BOEs. In order to realize that, management by BOE should shift from “one-size-fits-all control” to “individual support,” and BOEs should be institutions that accompany schools and support their self-propulsion.

IEN: What’s next? What are you working on or hoping to work on now?

Hirokazu Yokota: When I had looked at this Toda City before I joined as a deputy superintendent, I had the impression that it’s essentially a top-down reform with strong leadership from the superintendent. However, after being assigned by the Education Ministry to work here, I realized that I was mistaken. Although the BOE was running alone at the beginning of this reform (Stage 1), we’re now in Stage 2 (accompaniment) – many people within the BOE and schools have the same reform vision as the superintendent, and the BOE accompanies schools so that they can do cooking with raw materials provided by the BOE. Now, I have a feeling that we’re stepping into Stage 3 (self-propulsion) in which schools can prepare raw materials from scratch. What strikes me is that all the 18 schools in our jurisdiction are becoming leading schools that welcome visits from outsiders, as opposed to only a few leading schools and many other old-fashioned ones.

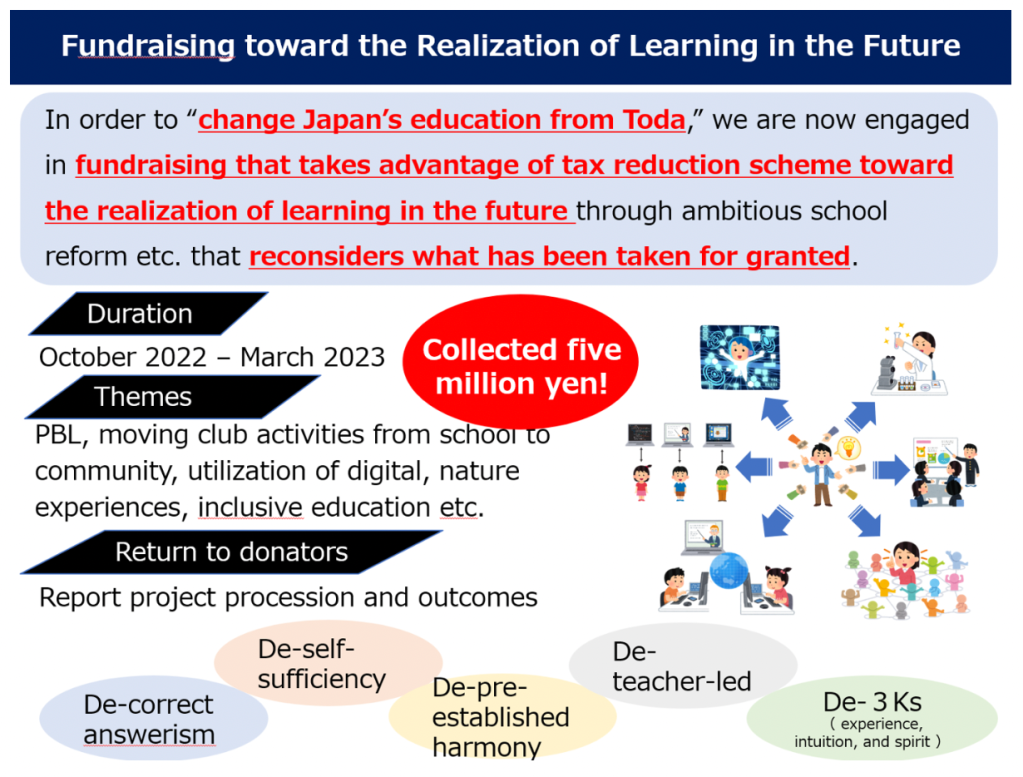

Through a dialogue with schools, I noticed that there are many things that schools want to do if and only if they have more money. Actually, my division’s budget accounts for only 4% of the total education budget of Toda City. With this budget constraint, what I came up with is essentially fundraising by the BOE. We ask our schools to submit ambitious reform proposals, and rather than expecting individual schools to do all the fundraising for their initiatives, we as a BOE collect money for them. We collected 5 million yen in the last fiscal year, and we distributed it to each school to implement. Although an exception for now, I believe this approach will also spread gradually, as the financial condition of governments has become even more challenging recently, and it will continue to be challenging in the future.