This week, Mohammad Shefatul Islam discusses the development and roll-out of online education platforms in Bangladesh. In the first part of this two-part interview, Islam talks about how he first got involved in edtech as a tutor and then describes how his work leading the development of several edtech platforms evolved during the school closures of the COVID-19 pandemic. The second part of the interview will explore the recent roll-out of a platform to support the implementation of a new competency-based assessment system this year. Islam is a civil service official within the Ministry of Education, with primary responsibilities as a Lecturer in Economics in government colleges. For the past few years, he has been on assignment at the Ministry of ICT and Telecommunication working on a program known as a2i, a collaboration between the Ministry of ICT and the Ministry of Education to help shape the future of education in Bangladesh.

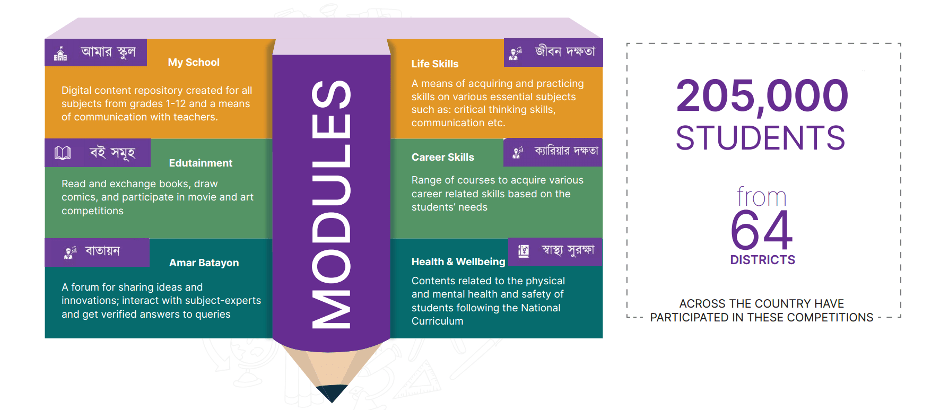

Islam has been a leading architect of the development of three different education platforms in Bangladesh: The Teachers Portal was established in 2013 to support blended learning and the development of teachers’ digital skills. Teachers can share presentations and teaching materials on the platform and access an online repository of multimedia materials. With over 600,000 registered, 60% of teachers from around the country have joined the Portal. Following the development of the Teachers Portal, Muktopaath was founded as an e-learning platform for educators and other professionals including doctors, police, and government administrators. In 2018, attention shifted to students and Konnect was founded as an “edutainment platform” to support the development of youth (13 – 18) through access to a safe digital environment that connects them to online and offline activities, educational materials, mentoring, advice, games and competitions. (K stands for Kishore, youth in Bengali.) All three platforms are featured in HundrED’s Global Collection of Innovations. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Thomas Hatch (TH): Can you first tell us a how you got involved in education?

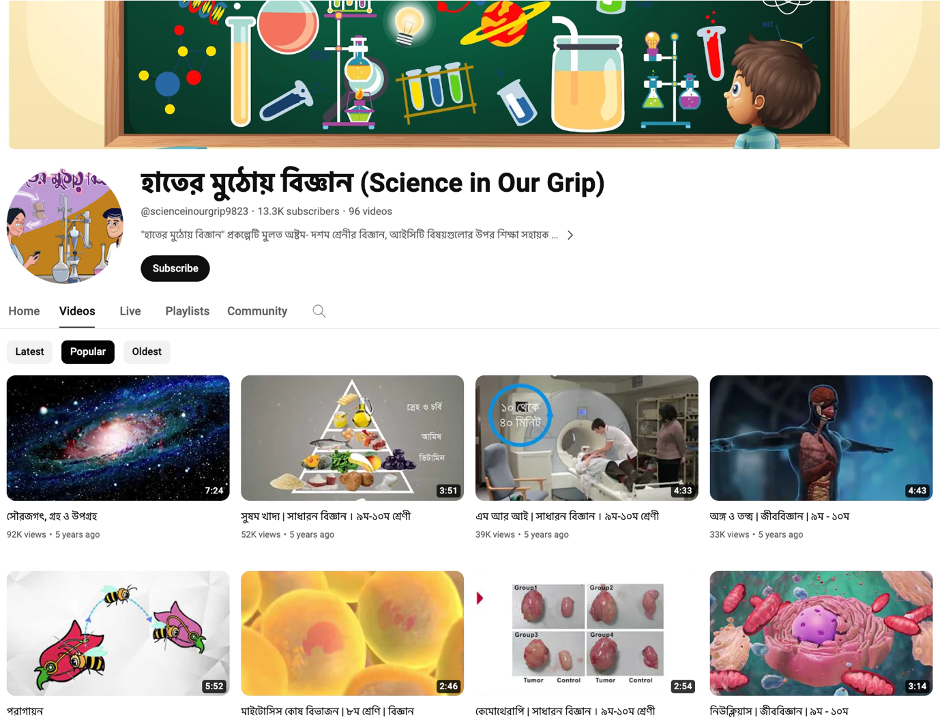

Shefatul Islam (SI): I started my education career when I was an economics student at university. At the time, I was tutoring high school students in subjects like biology, chemistry and physics to help them prepare for their national exams. In some cases, the students had trouble understanding the material because they hadn’t had any experience with it, and they didn’t have the lab facilities to explore it. For example, it was hard for many students to imagine what’s happening inside our bodies – what happens to the pancreas when it’s infected? These concepts were really abstract for the students, and they would often ask me if there were more visual ways to explain the topics. I used to go to YouTube to look up some of these things, so then I thought, “why not develop these videos in our own language?” So I reached out to some of my friends and some of my professors who were working with creative technologies and multimedia, and I started creating my own audio-visual educational content and my own YouTube channel, “Science in our grip.” I’m not managing it anymore, but the content is still very relevant because I made it like “micro-content,” not so much following the curriculum, but focusing on basic ideas from different subjects like “how do our organs work?” and “how do x-rays work?” It got quite popular and then I got an offer from the Prime Minister’s Office to submit a proposal and get some funds to expand my work. They gave me a grant for about $20,000 (USD) so I was able to develop content for all of Bangladesh. That really started my passion for education.

After I graduated with my Masters in Economics, I joined the civil service. In the civil service, there are several career options, such as administration, police, taxation. There are also four technical fields: doctors, teachers, agriculturalists, and civil engineers. Initially, I worked at a degree college for nine months. Then I was appointed as attached officer at the a2i programme, which is a flagship program for digitalization under Prime Minister’s Office. Then, at a very early stage of my career, I joined the Prime Minister’s Office. Usually that takes about twelve years or a certain level of seniority, but they already knew my work, so I was able to overcome a lot of things. I was given the instruction “you have no protocol to follow, you are licensed to innovate.” This is how everything happened from there.

Right now, I am on assignment at the Ministry of ICT and Telecommunication, where I have joined a2i (Aspire to Innovate). a2i started in about 2008 as a program within the Prime Minister’s Office, but it grew as part of the development of the “Digital Bangladesh Campaign” which began in 2009. Over the next ten years, there have been several campaigns like this that have contributed to the development of a lot of the components for the ICT infrastructure, but they were developed in isolation and weren’t really connected.

TH: You’ve been involved in the development of several major online education platforms, what were they?

SI: First, we developed the Teachers Portal, and then we worked on another product called Muktopath – it’s a capacity development and e-learning platform for teachers. We started it after gathering teacher input on their professional development needs. Then we saw the need for a student platform with academic and entertainment content, and we created Konnect. Now, we’ve tried to integrate everything into an ecosystem where each platform supports the others.

My current team is called “The Future of Education” at a2i in Bangladesh. From this team, we support the Ministry of Education in curriculum development and the development of various educational platforms and tools like manuals, and other resources.

Recently, we have developed a blended education master plan for the whole government, including 13 ministries that support the Ministry of Education in learning, training, and capacity development. After COVID hit, we started collaborating with each ministry, leveraging their support for the education system, and this is how we are operating as a catalyst within the government.

TH: Can you talk about how your work evolved during the COVID school closures?

SI: Even before the onset of COVID-19, we were developing a Business Continuation Plan (BCP) for Bangladesh. We recognized the potential risks when COVID-19 initially emerged in China and began spreading rapidly. Before it reached Bangladesh, government leaders, including the Prime Minister, [Sheikh Hasina] and her ICT affairs advisor [Sajeeb Wazed Joy] urged the Ministry of ICT to create a business continuity plan in case everything shut down. We were in the process of developing that plan and creating some kind of support system so that students and teachers could communicate, but we were never able to complete that plan before COVID struck Bangladesh. We only had about a week after the school shutdown to take action, so we developed television class content and broadcast it through the National Parliament’s television “Sangsad” TV channel.

We converted three schools in Dhaka into television studios including Dhaka Residential Model College, Cambrian School and College, and the Mohammadpur campus. These schools provided all the classrooms, the screens, and other necessary facilities. They also provided food since there was no food available in the restaurants. All of them were shutdown. There was no outside support at all. It was like fighting a war. Every day, we recorded content and then in the night we edited it for the television. And in the morning we would take the tape by bike to the national broadcasting center and just put in the cassette – it wasn’t even digital – and it would be live at 9 AM. The struggle was tremendous, but the commitment from the teachers was unprecedented. And the Minister of Education said, “Do whatever you need to do. I don’t care what it takes. The system should run.”

It was like fighting a war. Every day, we recorded content and then in the night we edited it for the television. And in the morning we would take the tape by bike to the national broadcasting center and just put in the cassette – it wasn’t even digital – and it would be live at 9 AM.

TH: How many teachers were involved in producing the televised lessons?

SH: From primary to secondary, about 200 teachers were involved in taping the lessons for different subjects, and, on any given day, we had studios set-up at three schools where we were simultaneously recording educational content in different rooms. We recorded about 50 events a day, because, within each school, we were recording in different rooms. For example, we started at 8:00 AM, for every two hours, one class was recorded. Teachers were so fluent that they never needed any scripts. The just stood before the camera and started the class with the interactive smart board. It was very easy after two or three days because they became used to it. What inspired them most was recording the classes and they’d be very tired at the end of the day, but then they’d see themselves on television the next morning, and they became superstars in the country. After that we didn’t have to ask them again, they just kept coming. We also got a lot of requests from teachers who said “I can do this too!”

For example, one of our very influential teachers who had just retired shared her experience with me after she conducted a live session. She had lived in Dhaka her entire life and she’d taught thousands of students. She realized after appearing in the taped sessions that tens of thousands of students were joining her from different parts of the country. They were saying “Ma’am show me this,” “Ma’am tell me this,” and she was crying when she was telling me “I’ve never felt this kind of respect before. I didn’t realize I could be so influential.” It was very emotional.

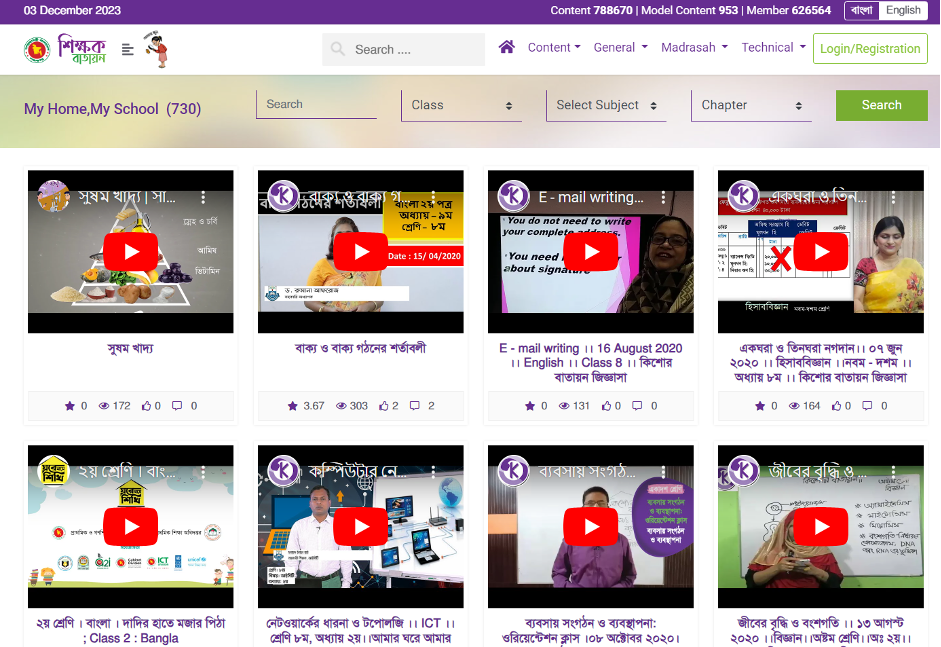

TH: What happened after you got the televised classes up and running?

SH: Then we had all this recorded content, but the television station couldn’t store it, so we started putting it online. Konnect was our key platform and we repurposed it to make it a repository. After the broadcast, if a student had missed they could just watch it from the platform. During the broadcast, in the newsline, at the bottom of the screen, we would include the information showing how to find the class on the Konnect platform. There was a big challenge at the time, with huge traffic from the all around the country, and our platform shut down for a few days, it was ready for all. We overcame that challenge, but that’s another story.

Then we thought of another plan to convert all our physical schools into online schools. To do that, we developed a framework for creating a school page that could be operated by teachers so every school could have its own page with its own name on Facebook. This way the teachers could offer live classes within structured times, and students could be seated at home and could join their different subject classes online. Teachers could then take these recorded classes and connect it to the Teachers Portal network so if any schools failed to provide live classes, their students could access the online classes from other teachers.

Konnectt’s facebook page served as the central hub where we shared the daily class schedules for all subjects. Within this framework, we instructed schools on how to proceed, recognizing that we couldn’t reach everyone through a single page. Each school had its own set of students, teachers, and parents, along with established communication networks. So, we advised all schools to create their own parent communication channels and encourage them to share our classes. Alternatively, schools that were ready could conduct their own live classes on their pages. After about a month, most schools had set up their own pages, and they were using various platforms to communicate with their students. Not only Facebook, but they used Zoom, they used WhatsApp. They used Google Meet and lots of platforms to leverage the time during the school closures.

But not all teachers were ready. Not all of them had the necessary data, phones, or expertise, and after a couple of months, we saw that many students still remained untouched and unsupported. So we went through a blended process from online to also offline and we provided some assignments from the National Curriculum Textbook Board (NCTB). NCTB shortened the curriculum for that time to focus on essential skills and competencies for each subject. We developed some problems and assignments and broadcast those again on television and social media; we also sent messages to parents by SMS; and some teachers wore suits and masks to go door-to-door to find students who weren’t engaged in online activities. We did a lot of online training using our Teachers Portal platform. For that, the faculty from the Teacher Training Colleges (TTCs) in Bangladesh were our key partners. There are fourteen of these TTCs in different parts of Bangladesh. They are very respected in their communities plus high school teachers generally go to them for training, so these faculty have influence over schools and teachers in their region. We distributed responsibility to the training colleges to train teachers in their own regions on what we called “online pedagogy” for the COVID-19 pandemic.

First, we instructed the faculty because most of them were not ready either. Every night we discussed, “what processes could work?” and “what innovations were being done around the world or anywhere in the country?” After a short time, we developed a small synchronous online course and around 500 people joined from around the country. We also opened up what we were doing in the central office. People were watching what we were doing on Konnect and Facebook and they were asking “How are you managing these things?” It was never written anywhere, but we shared our experience, like “you can position your camera this way,” “don’t talk too much,” and “you should have someone assist you.”

We had three different strategies. The first was high-tech using the internet and television. The second was low-tech using radio and SMS messaging. Third was no tech, sharing the assignments and instructions for students to do on their own.

In the end, we had three different strategies. The first was high-tech using the internet and television. The second was low-tech using radio and SMS messaging. Third was no tech, sharing the assignments and instructions for students to do on their own. But it wasn’t just about rote memorization, it was about: what is happening around you? How is your family’s wellbeing? What can be done in the future? We used their context, their wellbeing, and their imagination as their assignment. Not “read chapter 1.” The context was very important to the assignments, following the standards and the competencies of each grade.

Next Week: “Supporting a shift to competency-based learning Bangladesh“