Vietnam demonstrates that schooling can improve at a large scale, even in a country with a developing economy and over 15 million students. The majority of the Vietnamese population (nearly 86%) are from the Kinh ethnic group, but there 53 other ethnic groups. Some of these ethnic groups have long had high levels of literacy and education, but the Vietnamese government has also made a concerted effort to support the education of students from ethnic minority groups who live in rural areas and mountainous & remote regions and who experience higher levels of poverty. These efforts have contributed to near universal access to education at a relatively high level of quality. To learn more about how Vietnam’s education system has achieved this success, I visited Hanoi last year and talked to a variety of Vietnamese educators, policymakers and researchers. My conversation with Phương Lương Minh and Lân Đỗ Đứcat the Vietnam National Institute of Educational Sciences (VNIES) was especially instructive in providing insights into how schooling in Vietnam has improved in rural areas with ethnic minority students. The first part of this conversation centers on the efforts to improve education over the past thirty years, particularly in these ethnic minority areas. The second part looks ahead and discusses what might happen in the future as Vietnam rolls out a new competency-based curriculum and related textbooks. For related posts, see the Lead the Change Interview with Phương Minh Lương and A Conversation with Chi Hieu Nguyen about Vietnam’s responses to the COVID-19 school closures.

Lân Đỗ Đức is Vice Director of the Department of Scientific Management, Training, and International Cooperation at the Vietnam National Institute of Educational Sciences. Dr. Phương Lương Minh is a lecturer and coordinator of the Master Program of Global Leadership, Vietnam Japan University (Vietnam National University), and a collaborating researcher at the Vietnam National Institute of Educational Sciences. I am indebted to President Mai Lan and colleagues at VinUniversity for making this trip to Hanoi possible and to Dr. Le Anh Vinh, Director General of the Vietnam Institute of Educational Sciences (VNIES) and his colleagues for their support.

– Thomas Hatch

Policies for supporting access and quality of education in Vietnam

Thomas Hatch (TH): How has Vietnam managed to develop an education system that has almost universal access to education at a relatively high level of quality in a developing country of almost 100 million people?

Lân Đỗ Đức (LDD): After the war, the Vietnamese government realized education should be the key to changing human resources and economy, and we tried to maintain almost 20% of national expenditure on education. We also have policies supporting the general education sector, and then we have policies supporting minority education through financial aid. That can include support in some remote areas for secondary students to go to boarding schools. In the remote areas, especially in mountainous areas where ethnic minority communities live, beside the funding from local authorities, one key thing is support from village heads. They are not under the power of the local authorities, but they work with local authorities to support bringing students to school. The provincial and district authorities also provide instructions to lower levels, including villages, to work closely with the education agencies. Under the coordination of the People’s Committee, there is also close cooperation between government authorities and education agencies across provincial, district, and village levels.

TH: I understand that to support quality education in ethnic minority areas, the Vietnamese government is also trying to encourage students from those areas to train to be teachers. What steps have they taken to create a pathway into teaching for these students?

LDD: When there are not enough young teachers willing to go to rural areas, another key strategy is paying higher salaries as an incentive, with the allowance 50%, 70% , sometimes even two times higher. People also highly respect teachers and education. They understand the benefits for children and ethnic minorities. That’s why they strongly support initiatives to encourage and mobilize children to attend school. But one barrier is that teachers from outside areas often cannot speak the local ethnic minority languages when they come to work in rural or mountainous villages so it’s very important to train local minority people to become teachers. We have some policies that can make it a bit easier for minority students to enter teacher training programs. Usually, some ethnic minority students are nominated by their provinces to pursue teaching careers, called “cử tuyển”, and they receive some advantages like lower entrance requirements and financial aid from their provinces. In college, they also receive a lot of support. For example, when I was studying math education at the National University, there was one section of a math class that specifically trained in-service math teachers from ethnic minority areas. But after graduation, the students who receive funding from their provinces must return to work in local schools after graduation. For other students, it is different; they must find schools and jobs themselves after graduating.

TH: Do the provinces provide incentives and support for ethnic minority students wanting to study other fields besides teaching?

Phương Minh Lương (PML): Yes, there is support for ethnic minority students in other areas such as agriculture, medicine, economics, and tourism besides just education.To get into college, local authorities can nominate students to apply to university without entrance exams. We call this “Cử tuyển” – “sending to school” – local authorities select the students based on certain criteria, and, normally, students in this program are offered jobs by local authorities after graduating.But in practice, this is often not true. Not all students receive jobs from local authorities after graduating. So then a lot of the parents from ethnic minority groups see that there is no guarantee for their children to receive a job even though there was a commitment.

The power of the collective and social networks in education improvement

TH: In the US, we only hear about the “miracles,” but in Singapore it took 30-40 years to build an effective education system. In Vietnam, what was successful in the early days in the 1990’s? How were you able to reach people in rural areas and then get them into school and get them learning?

PML: That is the power of the collective that can be known as “power with.” There’s close coordination between authorities at grassroots levels and schools, with monthly meetings between the village or what we call the commune authorities and school leadership and educators. These include school officials like headmaster and representatives of mass organizations like the Women’s Union, Youth Union, and Study Promotion Associations at village level. These meetings are organized by the commune authorities, and they discuss all the problems related to the life of the local people in the village and in the school. Then if there is a problem, like there are children who have dropped out, then the authorities can support the school in that area and they can come to see why these children dropped out and whether there are any solutions to get these children back to school.

That is the power of the collective that can be known as “power with.” There’s close coordination between authorities at grassroots levels and schools, with monthly meetings between the village or what we call the commune authorities and school leadership and educators.

TH: But does that coordination really happen at an individual level – where they meet in a village and say, “These 5 children dropped out, let’s go find out why and get them back in school”?

PML: Yes, the head of the village head works closely with the teachers to find those children. It’s not always easy for teachers to find the children because sometimes the children may be far away in the rice fields or the forests for days helping their families to complete the harvest. But the village head knows how to communicate with those families to discuss the situation. He can mobilize the engagement of police, women’s union, youth’s union and youth in village in this effort. As such, they can quickly find these dropout children and their parents.

TH: Do you have an example or story of a specific student where this happened and a child dropped out and they brought him to school?

PML: In Lao Cai and Ha Giang provinces where I worked, the Hmong have some of the lowest school attendance compared to other ethnic groups. The children of the Hmong group may drop out if there is a marriage festival or another village event. The children also often drop out during the tourist season in the summer because foreign visitors come and the children drop out to act as tour guides so they can earn money. To deal with this, there are two things the school headmaster can propose to the Bureau of Education and Training at the district level. First, if it is a festival for the Hmong people, the authorities can allow the school to close for a few days. In some areas, 100% of the students might be from the Hmong group, so in that case all of the children might stay home. So closing the school is the first option.

Second, when children drop out to earn money, teachers have to work closely with parents and the village head to advocate for the children to attend school rather than earn money. The parents may support education, but some are too poor, or one parent may have died, and there is only one parent to earn money, so in that case, it’s really hard for the children to come to school. But the government of Vietnam actually provides some financial support for children in disadvantaged areas so they can receive nearly $1,000,000 Vietnamese Dong (roughly $40 USD) per month if they attend school. The money is for the children, but the teachers distribute it to the parents according to the regulations. Apart from money, they can receive rice as well.

TH: One of the arguments I’ve made is that one the strengths of the Singaporean and the Finnish systems is that they are both highly connected and socially networked, both formally and also informally. Even though people are spread out in Vietnam, particularly in rural areas, it sounds like people are still relatively well-connected?

PML: Related to communication and connections, I’ll tell you a story from my experience. In 2011, I did fieldwork for my dissertation in Ha Giang province. It is an area with a high proportion of ethnic minorities – over 70% in some villages and 100% ethnic minorities in others. There was a non-governmental organization (namely ActionAid Vietnam that had a medical care program for children, and one day, my colleague went to a school with a doctor to do some health examinations of the primary and lower secondary school students. The doctor found some children that had teeth that needed to be pulled, otherwise, they’d become infected. Unfortunately, a terrible rumor started that the teacher pulled the children’s teeth to sell to the Chinese people for 15 million Vietnamese Dong per tooth! And the next day all the children were gone, and none of them came to school. Of course, this created a real headache for the local authorities, who had to figure out how to convince the children to come back.

We all thought it was strange that all these parents had the same information though they lived very far from each other. The Hmong people are very spread out, with several households on each mountain. That was in 2011 and the Internet connection did not work well yet and mobile phones also weren’t common there. But the Hmong people had an informal channel to communicate and share that information so the next day, no children went to school. The local authorities at the district and commune levels and the headmaster and the healthcare center director had to come to each village and convince the parents the rumor wasn’t true and get them to bring the children back. The village head who is from the Hmong people has a good reputation, so he can gather all the Hmong households and get the teachers and the doctors to explain what happened.

The Hmong people had an informal channel to communicate and share that information so the next day, no children went to school. The local authorities at the district and commune levels and the headmaster and the healthcare center director had to come to the village and convince the parents the rumor wasn’t true and get them to bring the children back.

Community engagement and educational improvement

TH: It seems like you could argue that Vietnam lacked the educational infrastructure and the money that some other systems have had, but it has had the social and cultural infrastructure that connects communities and maybe we have lost some of those connections in many communities in the US. Do you have some other examples of parent or community engagement in schools?

PML: I can talk about another example of parent engagement in ethnic minority areas. In one of my chapters, I wrote about inequities for ethnic minority children in getting access to school. In first grade in primary schools, they have to learn the Vietnamese language, but without good language preparation, and this challenges the enactment of their rights under Article 5 in the Vietnamese Constitution to learn in their mother tongue from an early age – Article 5 of Vietnam’s Constitution states: “Every ethnic group has the right to use its own language and system of writing, to preserve its national identity, to promote its fine customs, habits, traditions and culture.” So we mobilized the ethnic minority parents who are good at the Vietnamese language to come to the school to help the teachers. Most teachers are Kinh people, and they can’t speak the local languages, but the parents can act as translators between children and teachers in those first months until the children understand the teacher and the teacher can understand the Hmong children. That’s a great initiative for bridging education and removing language barriers. Additionally, parents are also willing to contribute their labor to cook for children when schools lack the money to pay for support staff, so these are some good community engagement practices.

Article 5 of Vietnam’s Constitution states: “Every ethnic group has the right to use its own language and system of writing, to preserve its national identity, to promote its fine customs, habits, traditions and culture.” So we mobilized the ethnic minority parents who are good at the Vietnamese language to come to the school to help the teachers.

TH: You used the phrase “we mobilized parents,” but what does that mean? How did you do that?

PML: Most parents are aware that, when children have access to education, they can have better lives and for that they need to know Vietnamese. But as I said, ethnic minority groups often live far from the commune centers, so we sometimes establish satellite schools in the villages. Then the parents can see that when the children come to school, they are having a lot of fun. They can see the children singing and reading stories in Vietnamese, and they can see the children’s happiness. It’s that simple – if children enjoy the class, parents will come to support them.

However, it is not easy for the parents to get access to the classrooms without approval from the school. That’s the reason why this model of parent engagement functions with the support of the NGO’s. The NGO’s see the need to engage the parents to help the teachers. It is not that the community people want to come to the school, and they are warmly welcomed by the school. It is the NGO that says to the school it would be good if you have the support of the parents. Recognition is very important here. When the school recognizes the contribution from the parents, then it works. Otherwise without any recognition, there is no chance for the parent to get involved in the school system, yeah. The same for the NGO as well. If they don’t request that the school recognize the contribution from the parents, then it doesn’t work.

The aims of education and the right to mother tongue education

TH: the education system is focused on improving economic opportunity, getting students into higher education and the workforce. But as you have pointed out in some of your research, this comes at a cost if attention is not paid to local culture and history. Does the government understand this problem, or is it more focused on strengthening the overall economy and education system?

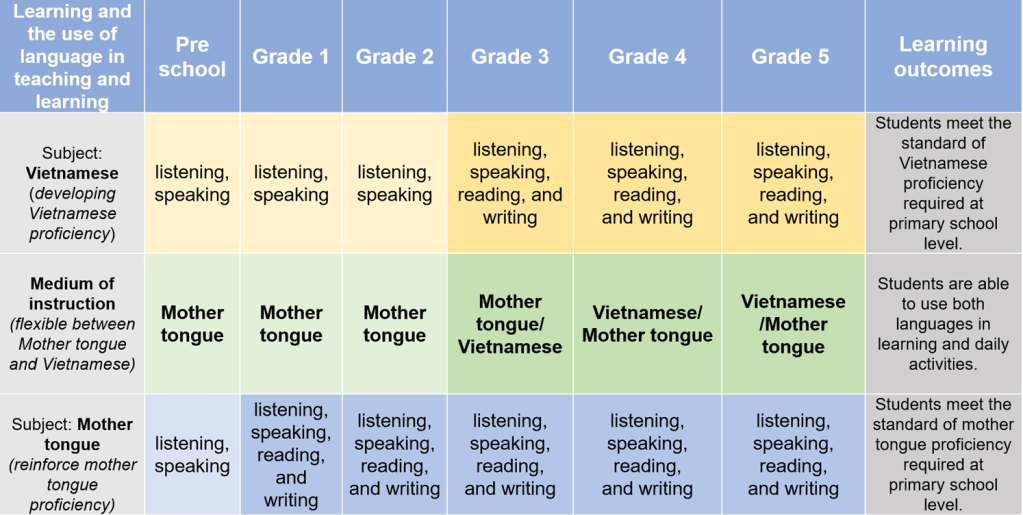

LDD: The government wants to preserve the local culture, and that’s why we also developed the bilingual teaching program funded by UNICEF. It ran for almost 10 years from about 2006 to 2015. Several million dollars were provided to develop learning and teaching materials in minority languages, and the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) and VNIES are continuing to work to support teacher training and learning materials for bilingual education and mother tongue instruction in some provinces. But some of these languages don’t have a written form so it is not easy.

PML: It is regulated very beautifully in the policies that all ethnic groups have a right to education in their own language. But in practice, even though the government wants to support them, it is not feasible to do so because of limited resources. For example, without a writing system, we cannot preserve the languages; if we don’t have teachers who are able to teach in the languages and we don’t have the curriculum and textbooks to teach them, it doesn’t work. Right now, there are only three languages that UNICEF has funded for textbooks (including Mong, J’rai and Cham). So we try to promote and implement Article Five in our Constitution, but it depends on the available conditions

“It is regulated very beautifully in the policies that all ethnic groups have a right to education in their own language, but in practice, even though the government wants to support them, it is not feasible to do so because of limited resources”

Next in this series: Looking toward the future and the implementation of a new competency-based curriculum in Vietnam: A Conversation about the evolution of the Vietnamese school system with Phương Lương Minh and Lân Đỗ Đức (Part 2)