Nearing the end of 2024, it’s an opportune time for Looking Back to Look Forward. In this case, that means looking back on the standards-based education reforms of the 1990’s through a reflection and report from Mike Kirst. As Dick Jung describes in his book and blog series about Kirst’s career and impact, Kirst is an “uncommon academic;” at the same time that Kirst has been a professor of education at Stanford University he has also been an influential public servant. Kirst has been a trusted advisor to California’s former Governor Jerry Brown, and Kirst served four terms as President of the California State Board of Education. This week, IEN highlights Kirst’s continuing influence by sharing a quote from a blog post Kirst wrote for Policy Analysis for California Education along with excerpts from the latest installment of the “Uncommon academic” blog series. Both the blog post and the 21st installment discuss the Kirst’s latest report for the Learning Policy Institute on some the standards based reforms in which he has been intimately involved. (For a previous post on Mike Kirst’s career see Making public policy work for education: Reflections on the career of Mike Kirst)

“After ending my fourth term as president of the California State Board of Education in 2019, I have begun to reflect, in my sixth decade of education policy, about what I did right and what I should have done differently. In my time on the board, we organized many policies around and integrated them with the state standards in English Language Arts, Mathematics, and Science. California made significant progress toward creating coherent and aligned state policies aimed at helping local districts implement the Common Core State Standards. We coupled these policies with a new, more equitable funding system—the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF)—and a multiple measures accountability system.

Looking back, it was naïve to believe that these policy reforms alone would be enough to achieve the desired impact. We successfully corrected for some of the failures of prior attempts to generate educational improvement by over-focusing on accountability (embodied by policies like No Child Left Behind). I failed, however, to realize the extent to which accountability-focused approaches of the past had underinvested in building the system capacity necessary to support educators in developing the knowledge and skills that would enable them to teach successfully in the new ways that the new standards demanded. Our policies did not do enough to overcome this deficit.”

— Mike Kirst, Looking Back, Moving Forward: A Vision for Instructional Capacity in California

A Clarion Call for Reform from an ‘Uncommon Academic’ Excerpts from the 21st installment of the Mike Kirst Biography Project produced by Richard Jung

This installment of the Mike Kirst Biography Project features Mike himself, speaking of his rationale and intentions as he toiled, in his eighties, over the lessons from decades of research and policymaking. This installment allows you to see and hear, through video and audio clips, Mike’s sense of what is most important for policymakers to know and do toward lifting local education practices to meet high standards (standards-based reform).

He elaborates—in his own words, often with captivating metaphors—the answers to three questions:

- Why has he spent the first five years in his eighties researching and writing this Report?

- Why have many K-12 education reform efforts, including his own, fallen short?

- What should be done differently going forward?

So, let’s take a more personalized plunge into the education policy approach of standards-based K-12 education reform, enhanced by recent interviews with Mike.

Mike’s “More-Focused Heart” Years

In the report’s first sentence, Mike writes that its genesis was when he turned 80. His longtime Stanford colleague, walking partner, and hand-selected successor as California’s State Board of President, Linda Darling-Hammond, then President of Learning Policy Institute (LPI), and he had “discussions.” He agreed with her and others that “[a]after almost 60 years of working full-time in education and doing research, I thought it was a good time for me to reflect on” that previous work in federal and state education reform efforts “and to synthesize the research focusing on the impact of standards-based reforms.”3

As Mike turned 80, he reviewed the current research literature. He saw that there was a much deeper understanding of how difficult it is to change classroom instruction and that California had no master plan or strategy based on that research, particularly for math instruction.

Mike persisted for the next three years, through his early 80s, to gather and reflect on this research at a time when, as he writes in this “Preface,” “the COVID-19 pandemic was the overwhelming focus of education policy.” A series of LPI editors worked with him to refine and polish the Report. And now, some five years after those initial discussions with Linda Darling-Hammond, Mike believes “public attention” might be “more receptive to classroom instruction issues and the core subject matter curricula of k-12 schools.”4

Professionally, Mike’s septuagenarian years had hardly been “serene,” unlike those of suffragist Scott-Maxwell noted above. During his stint leading the state board of education and working hand-in-hand with then-Governor Jerry Brown from 2011 through 2019, Mike had led the charge with others to pass and then start to implement one of the country’s most successful school finance and governance reforms, the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) which enhanced both quality and equity in the state’s distribution of funds and accountability for their use.5

With others, he began working quietly—perhaps less quietly recently—behind the scenes to stir up enthusiasm about the standards-based reform ideas embedded in the LCFF, e.g., that standards-based reform involves setting standards and aligning curriculum, instruction, and assessment practices to those standards to ensure that all students have the opportunity to meet high expectations, thereby enhancing both quality and equity.

By the time he was almost 82, in July 2021, like writer and activist Scott-Maxwell, Mike was becoming “more intense” as he aged. He began publicly to “let the cat out of the bag” about his sense of the critical next steps toward fully implementing standards-based reforms when he delivered his acceptance remarks as he received the prestigious James Bryant Conant Award from the Education Commission of the States.

In his acceptance speech (this clip below), he begins, as is his wont, with a sports analogy—of “being in the fourth inning of a nine-inning ballgame when we got rained out by Covid”—to summarize California’s complex education policy situation as implementation of the reforms in the LCFF were to roll out. He had already highlighted that “local capacity building” is the place to start and emphasized that again. There’s a lot to unpack from this two-minute clip. Let’s first listen in:

Even amid the COVID-19 shut-down of schools across California and most of the country in 2021, Mike looked into the future and beyond when K-12 schools would be fully operational. He drew upon his decades of education policy research and policymaker experience to note, “States… can’t mandate—we can’t even incentivize very well what teachers and principals and school people do together.” Further, “when the teacher closes the classroom door, she or he has the impact, in effect, of a pocket veto, over whether state policies are implemented or not.”

As a politics of education expert, the pocket-veto power of teachers once the teacher closes the classroom door is a metaphor that Mike has often used to depict that state, federal, or even local policymakers cannot merely “mandate” or require classroom practices to improve instruction.

As you can hear in this clip, Mike had been looking in the U.S. and other countries for ways to build the “massive infrastructure” needed to effect reforms in California. He cites Ontario, Canada, Singapore, Australia, Finland, and some states in America, several of which were sites for his early policy work.6 He offers this tease: “I can’t describe all of this to you now, but you’ll be hearing more from me about …”big thinking, big infrastructure, big capacity building, and state-wide scale-up… in the next months and years.”

Now, three years later, Mike has found a more apt metaphor for the complexity of improving classroom instruction; it’s an analogy he picked up from Harvard University’s Richard Elmore.7 Mike now observes that “education policy, particularly at the federal and state level, is like a shell of a turtle. The shell’s important for the turtle, but moving and important, complex parts are underneath. Mike believes that “at this time in my career, my focus is on the operating parts of the turtle rather than on the ‘shell’ of finance and governance.”8

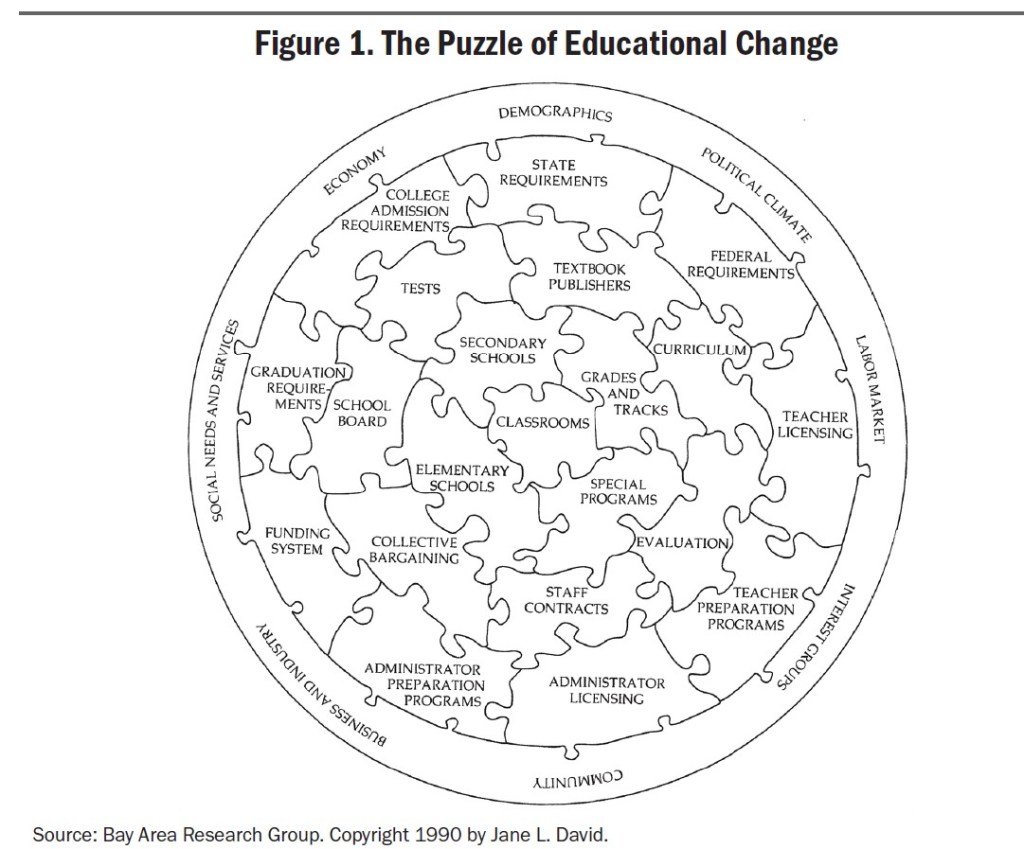

To illustrate this portrayal of education policy by drawing on the Elmore turtle analogy, he borrows an image from his research colleague Jane David, who calls it “the puzzle of educational change.” Mike explains in the Report, “David’s diagram is daunting in its complexity and helps illustrate why it has taken years of effort even to begin to align the supports for standards-based reform, long after support for the concept itself took hold.” In other words it’s one thing to create strong standards. It’s quite another for “those standards” to make “their way into instruction” inside the classroom.9

Massive Infrastructure Needed for Scale-Up

The publication of Looking Back to Look Forward is evidence of Mike’s focus since his Conant Award acceptance speech three years ago. He had been deliberating on the nature of and the necessity for a “massive” post-COVID standards-based reform of California’s K-12 education system. The word “massive” appears in the Report nine times.

In his “long paper,” he states that all states, “even those…in the midst of piecemeal improvements to instructional capacity-building…would benefit from broader thinking and planning. The objective should be to create a lasting education infrastructure similar to the federal interstate highway system of the 1950s.”10 Mike’s point with this analogy to the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act is that it took 15 years to pour all the concrete to complete our country’s interstate highway system. With COVID hitting only a few years after the standards reform legislation in California was enacted, much of the “concrete” in terms of essential “capacity-building” for improving instruction had only begun to be “poured” or put in place.

“The key word is ‘capacity-building’ of local educators.”

Recall that in the Conant acceptance speech, he told the audience that “the keyword is ‘capacity building” at the local level, that “this capacity building has many aspects,” and that education reformers in other countries had told him, “we build this capacity building into the districts” and “we build it into every day” and “into the professional work of teachers through expanded professional development.” Mike details this local capacity effort in other countries and states, including Massachusetts and Louisiana, on pages 69 through 76 of Looking Back to Look Forward.

Mike Notes Two Caveats about the LPI Monograph

Mike’s thinking evolved in several significant ways as the publication of this paper “percolated.” Most notably, he, with other colleagues, now more fully admits “how hard it is to scale up PD [professional development]…to statewide implementation.”11 He also recently reflected on two caveats about the paper, especially its conclusions. Click on the link below to hear more from Mike about the first of these:

Mike Kirst: A limitation of the LPI monograph: “The paper ends very vaguely…” (audio, 35 seconds)

Mike is delighted that the monograph is now out but laments that it “essentially ends with a plea for a detailed plan with very little detail.” He continues, “I’ve learned now more than I had in the paper about how hard it is.”12 after recently working with several groups–including the California Collaboration on District Reform and the California Math Roundtable, which he refers to jointly as the “collaborative” in this interview excerpt. Voicing some frustration, Mike concludes, “There is no detailed strategic plan in this paper because nobody has ever done one.”

He asks rhetorically specifically for math, “So what’s your strategic plan for teachers to teach the math curriculum in California when the students are all over the map in math? You have so much diversity, particularly in that subject, even within middle-class and upper-class classrooms. And so that’s why it’s not there.”13

The second limitation Mike now sees in his Report is that he failed to more forcefully note that educational policy has been imbalanced too frequently, failing to emphasize capacity-building as much as accountability. Click on the link below to listen to how he explains this limitation in his own words:

Referring to Harvard’s famed education policy researcher, Richard Elmore—what Mike calls “Elmore’s Law—Kirst notes that for too many years, policymakers have put too much emphasis on accountability up front rather than understanding that successful implementation requires more initial investments in capacity building.14 Using a scale of justice metaphor, he notes that even a recent California education funding initiative had still made this mistake when it had “ratcheted up accountability but with no real systematic capacity” and that it’s “a common mistake” among policymakers to “lead with accountability and never get around to capacity building.”

Still Living His Mantra

Before LPI published Mike’s “long paper,” Kirst was cautious in what he said publicly about his behind-the-scenes efforts to advance his standards-based reform project, which is close to his heart. That didn’t stop others from wanting to hear more about Mike’s education reform ideas. Earlier this year, for example, Dr. Lisa Andrew, President and CEO of Silicon Valley Education Foundation, hosted for Forbes Books a two-part series offering what she summarized as “a unique bird’s eye perspective on education’s challenges and opportunities,” with the impatient foot-tapping title of “They are Waiting For Us”, perhaps unwittingly reflecting Mike’s wanting for the past several years to get out the ideas now appearing in this LPI paper.

Mike begins this Report with more than a hint of that impatience, noting that the COVID-19 pandemic became “the overwhelming focus of education policy for three years.” So, he and LPI leadership decided to “wait until public attention was more receptive to classroom instruction issues and the core subject matter curriculum of K-12 schools ” to release the monograph.15 With the publication of this Report early in the 2024-25 school year, Mike boldly exhorts, “Now is not the time to give up on state standards.” Instead, he insists, “There is no better time than now to proceed.”16

We note, however, that Mike’s “now” is tempered in his “long paper’s” closing observation that “providing sufficient capacity-building for teachers in making major instructional shifts is more realistically implemented over a decade or more rather than in… a few years”—cautioning policymakers once again to adhere to his time-proven policy reform mantra of: “patience, persistence, humility, and continuous improvement.” reiterated in the Report’s concluding sentence.”17

See 21st Installment: A Clarion Call for Reform from an ‘Uncommon Academic’ for the complete post, notes, and citations.