Can real changes be made in a system dominated by exams and academic pressure? Thomas Hatch explores this question in the second post in a series drawing from his conversations with Chinese educators and visits to schools and universities in major urban areas like Beijing, Nanjing, Shenzen, Shanghai and Suzhou. The first post in this series described how some innovative schools in China are putting in place more student-centered learning experiences. Future posts will discuss the use of AI in an experimental primary school; increasing concerns about students’ mental health; and the technological and societal developments that may allow for the emergence of a more balanced education system.

For previous posts on education and educational change in China see “Boundless Learning in an Early Childhood Center in Shenzen, China;” ”Supporting healthy development of rural children in China: The Sunshine Kindergartens of the Beijing Western Sunshine Rural Development Foundation;” The Recent Development of Innovative Schools in China – An Interview with Zhe Zhang (Part 1& Part 2);” “The Desire for Innovation is Always There: A Conversation with Yong Zhao on the Evolution of the Chinese Education System (Part 1& Part 2);” “Beyond Fear: Yinuo Li On What It Takes To Create New Schools (Part 1);” “Everyone is a volcano: Yinuo Li On What It Takes To Create A New School (Part 2);” “Surprise, Controversy, and the “Double Reduction Policy” in China;” ”Launching a New School in China: An Interview with Wen Chen from Moonshot Academy;” and ”New Gaokao in Zhejiang China: Carrying on with Challenges.”

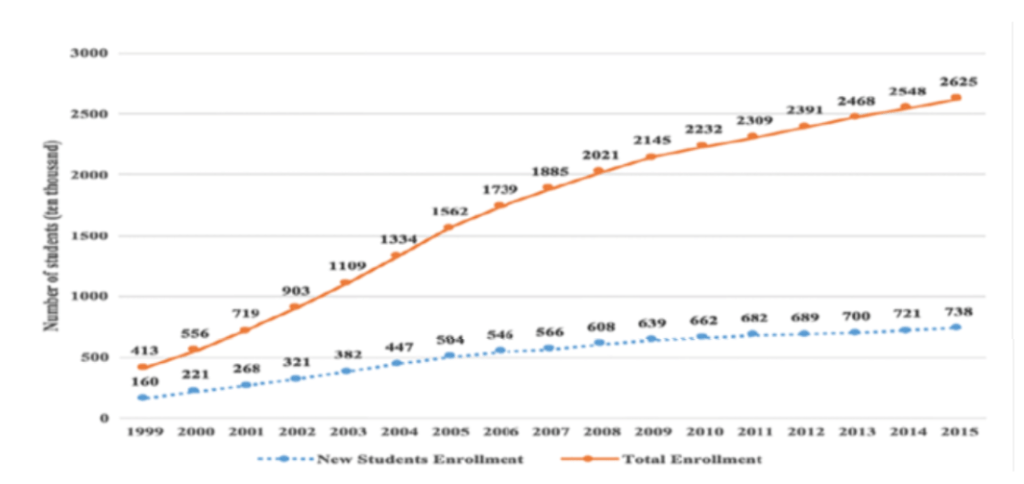

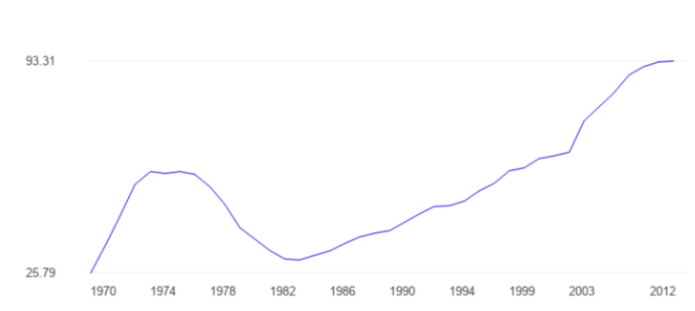

I’ve always heard that Chinese schools – in the grip of the Gaokao, the college entrance exams that drive so much of the academic pressure in China – are unlikely to change. But during my visits to schools and universities there over the past two years, it was clear that education in China has changed, in numerous ways, both in the last 40 years and just in the last few years as well. Those changes include the achievement of near universal enrollment through lower secondary school and dramatic increases in the number of students enrolling in college – including a five-fold increase in the decade between 1999-2009. Enrollments in kindergartens have also risen over 25% since 2012, with more than 90% of preschool-age children enrolled in kindergarten by 2023.

Along with those dramatic developments, China has made significant changes in educational policies that have helped to create the conditions – and “niches of possibility” – that can support more student-centered and innovative educational experiences at all levels of schooling. In fact, since 2001, the Guidelines for Pre-school Education have emphasized development of child-centered play. In addition, a new national pre-school law that took effect in 2025 specifically prohibits the introduction of an elementary school curriculum into kindergartens and pre-schools. For older students, changes in the Gaokao and in the regulations governing private schooling that created some flexibility to develop more innovative schools and learning experiences. At the same time, these kinds of changes in policies reflect somewhat conflicting purposes that have also contributed to the academic pressure and competition that continues to reinforce a focus on conventional academics.

“[C]hanges in policies reflect somewhat conflicting purposes that have also contributed to the academic pressure and competition that continues to reinforce a focus on conventional academics.”

Changes in the Gaokao

Although many of us in the US think of China as a centralized government that exercises tight control across the whole country, provincial and municipal governments also have considerable discretion, particularly when it comes to education. The regional differences in policies and policy enforcement may allow for the development of alternative educational approaches in some places rather than others. For example, the kinds of micro-schools that have emerged in the US since the pandemic, began to appear in some parts of China even before the school closures. Dali, described as China’s “hippie capital” or “Dalifornia,” became a popular destination for remote workers during the pandemic and others looking to get away from everyday pressures. It’s also a place where new, small educational programs, many unsanctioned, have sprouted for students who have dropped out or want to get away from the academic pressure.

Micro schools aim to make a major impact, China Daily

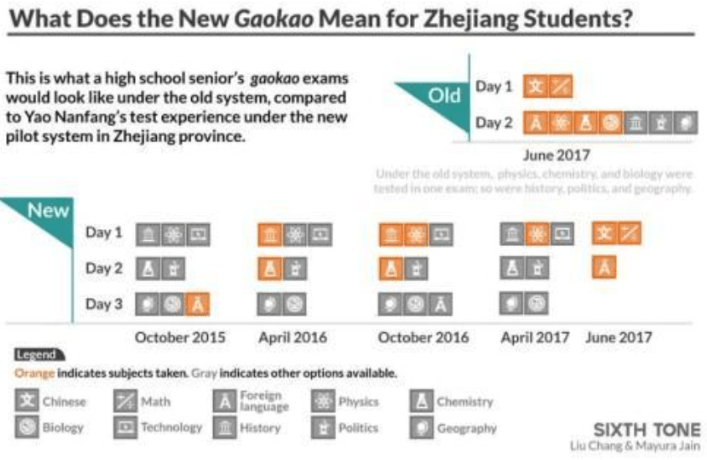

Among the most significant differences in educational regulations, local governments can even produce different versions of the Gaokao with different questions and cut-off scores. That means that any central attempts to change the Gaokao have to be coordinated across regions. For example, in 2014 to help reduce some of the academic pressure, the central Chinese government launched initiatives to provide students with more flexibility and choice in the exams. As Aidi Bian reported in “New Gaokao in Zhejiang China: Carrying on with challenges,” an Education Ministry document guiding the Gaokao reform specified that provinces were to adapt the reform based on local context. In Zhejiang, one of the first provinces to undertake the reforms, key changes included requiring only three compulsory exams – Chinese, mathematics, and English – and allowing students more choices in the three elective exams, which include subjects like chemistry, biology, geography, politics, history, and technology. In addition, instead of having to take all the tests once in June, students were allowed to take the elective subject tests starting in the second year of high school (in October and March). They can also take each elective subject test and English twice and use the highest grade for their admissions application.

The changes did not always achieve their aims, however, as some have tried to “game the system” by choosing subjects that top students are less likely to take. In addition, taking some electives earlier may help some students but it also prolongs the Gaokao schedule and it means that the test pressure is distributed throughout the high school years. Furthermore, reflecting the regional variations, only 8 of the 18 provinces that were originally scheduled to undertake the reform had started the new policy by 2018.

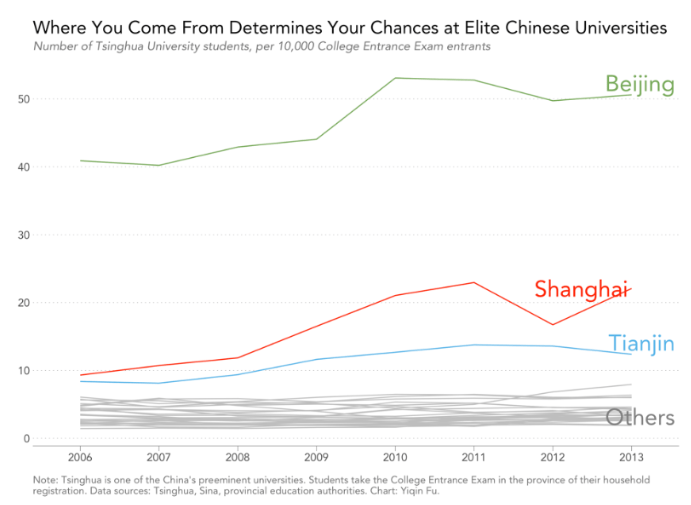

Complicating matters further, over the years, different regions and municipalities have set different cut-off scores and created “extra-point” schemes to increase access to higher education for certain groups. Although the government has placed more restrictions on these schemes in recent years, historically, “bonus” points have been awarded to members of some minority ethnic groups to support their assimilation into society, to the children of Chinese who return from overseas, and to children of Taiwanese residents. Some provinces have also awarded points to those who demonstrate “ideological and political correctness” or have “significant social influence” including children of Revolutionary Martyrs, and some categories ex-servicemen Many of those I spoke to also explained to me that students in some of the larger cities have a better chance to get into China’s top universities than their peers from around the country. That’s because Tsinghua University, Peking University, and other top institutions have admissions quotas that explicitly admit more students from urban centers like Beijing and Shanghai.

These kinds of policies have been part of the expansion of higher education that has benefited those in all economic classes, but that has also fueled rising inequality and a growing rural-urban divide. Given these problems, the central government has advocated for the elimination of the Gaokao bonus schemes that contribute to these inequalities. However, these advantages are part and parcel of a paradoxical system that embraces exams and competition as the fairest and most transparent way to identify academic potential but can also allow for some special privileges and where some may try to “game the system.” The recognition of special privileges is reflected in the use of another term I frequently heard, guanxi, which refers to the importance of networks of trusted friends and families that can provide access to power and social and economic advantages. Although as an outsider I find it hard to understand how both the tradition of national entrance exams and guanxi can coexist, both are deeply rooted in Chinese history and culture, developing a thousand years ago in imperial China where the rule of law was not well-established and where many people had to rely on trusted family and friends for support and protection.

Changes in policies related to private schooling

At the same time that there have been contradictory efforts to change the Gaokao, changes in education policies gradually allowed the development of private schools and encouraged foreign investment in the education sector. In concert with the changes in regulations that opened up the economy after 1977, school options for students expanded significantly, including the development of private primary and secondary schools that prepared students for admissions to universities in the UK, the US, and elsewhere. Those developments contributed to the establishment of 61,200 private schools by 2003, serving over 11 million students; but by 2020, that number had increased to almost 180,000 private schools enrolling more than 55 million students. Those numbers amounted to almost one third of all primary and secondary schools in China and almost one fifth of all students.

In recent years, however, new regulations governing private education have reversed the expansion of private primary and secondary school options. In 2021, for example, a new “Law on Private Education” went into effect. The 68 articles of the new law restrict how education can be monetized; establish stronger oversight of private and non-profit operators of schools; and require the curriculum of private schools to align more closely with those of public schools with adherence to the national curriculum more strongly enforced. In addition, foreign entities are prevented from having ownership stakes in Chinese private schools and foreign textbooks have been banned. Regulations promoting “patriotic education” in all schools have also been established.

“The 68 articles of the new law restrict how education can be monetized; establish stronger oversight of private and non-profit operators of schools; and require the curriculum of private schools to align more closely with those of public schools”

Within this changing policy context, the economic downturn, a declining population, and the COVID pandemic, the rush to open new private and international schools has been followed by a wave of school closures. To avoid closing, other private primary and secondary schools have tried to attract more students by diversifying their offerings. Those changes include offering programs that lead to entrance to Chinese universities in addition to their programs leading to other university qualifications. As one account of the changing landscape of international schools put it, “Whether it is a newly built international school or an old international school, “domestic college entrance examination courses + AP/A Level courses” and ‘domestic further study + overseas study’ have become high-frequency hot words in the enrollment brochures.” Ironically, these efforts to diversify their offerings contribute to the challenges that private schools face in trying to create a more balanced educational experience that distinguishes themselves from government subsidized schools.

Changes in tutoring and academic demands?

At the same time that the Chinese government put more limits on private schools, they also enacted the “Double reduction policy” which sought to address the increasing pressure on students and curb the explosive growth of the private tutoring sector. The policy, Opinions on Further Reducing the Burden of Homework and Off-Campus Training for Compulsory Education Students, both limited the amount of time students in primary school could spend on homework and banned most private tutoring (reflecting the “double” in double reduction).

Following the initial implementation, some surveys reported that many Chinese parents agreed with the double reduction policies and felt their concerns about their children’s education had eased. At the same time, the restrictions mean that many teachers have had to take on more responsibilities, more work, and more pressure. One study, published after the policy went into effect found that over 75% of Chinese teachers experienced “moderate to severe anxiety” with almost 35% of primary teachers and over 25% of middle school teachers at high risk of suffering depression. Chinese policymakers have even acknowledged that teachers are “teachers are more tired” and “teachers’ anxiety has obviously increased compared to before.”

“[Many Chinese parents agreed with the double reduction policies and felt their concerns about their children’s education had eased. At the same time, the restrictions mean that many teachers have had to take on more responsibilities, more work, and more pressure.”

At the same time, the policy had an immediate impact in reducing the availability of private tutoring and other supplemental education programs, that, ironically, may have contributed to the stress and concern of the many students and parents who felt they needed extra support to compete in the exam-based system. Just seven months after the implementation of the policy, the Ministry of Education reported the closure of over 110,000 companies, almost 90% of the companies focused on in-person or online tutoring in primary and middle schools. Those changes in turn contributed to stock prices of many tutoring-related companies to drop by 90% or more. According to some accounts, one of the tutoring CEO’s, on his own, lost over 10 billion dollars because of the policy. With a corresponding loss of over 100 billion dollars in China’s education market, the closures contributed to dramatic reductions in the availability of related educations jobs in China and layoffs of hundreds of thousands of workers. A once growing market for English-speakers to tutor Chinese students online also dried-up almost overnight.

Under these conditions, those tutoring-related companies that found ways to continue operating often did so with higher fees that can contribute to greater inequities. Correspondingly, some parents reported that the costs of private tuition have doubled for them, “Our burden has not been reduced at all,” one parent lamented, and described the situation using a common expression that likened the continuing competition for entrance into the top universities to “thousands of troops and horses pushing and shoving to cross a single-plank bridge.”

“Our burden has not been reduced at all,” one parent lamented, adding that the continued competition for entrance into the top universities is like “thousands of troops and horses pushing and shoving to cross a single-plank bridge.”

In the latest set of complexities and contradictions, additional policy changes, particularly a decision to reduce the number of middle school students who can enter academically-oriented high schools have also increased the competition for high scores on the Zhongkao, China’s high school entrance exam. Implemented at least in part to address labor market shortages, the earlier policies on national vocational education development require that approximately 50% of high school students attend vocational high schools. But that reduction in the percentage of students who can attend the academic high schools, have led some to conclude that the Zhongkao is the new Gaokao, generating even more academic pressure on students and parents at an even earlier age.

Later this month: Could concerns about academic pressure lead to real changes in conventional schooling?