In the second part of this conversation, Alma Harris and Carol Campbell talk with IEN Editor Thomas Hatch about what has (and has not) happened since the release of their report “All Learners in Scotland Matter- National Discussion on Education,” from the National Discussion on Scottish Education almost one year ago. They also share lessons for those who might want to pursue a similar large-scale public engagement and explore how this kind of dialogue could offer a new process to support educational change in the future. In part 1, Harris and Campbell discuss their initial steps and the procedure they pursued as facilitators of the dialogue. The interview was edited by Sarah Etzel & Thomas Hatch.

TH: Can you give us a quick sense of some of those things that you felt you had to put in the report to make sure that children’s concerns were honored?

CC: We had a large volume of responses, but we wanted to make sure that we honored the children’s voices by ensuring that their views, including the challenges they were experiencing as well as their hopes for the future, were included in the report. Plus, Alma and I were personally involved in lots of events and communications where we either heard children and young people’s voices directly or through adults speaking on their behalf, so there were stories that we carried with us, and they had an impact that we wanted to make sure were included. For example, a major issue is additional support needs. Scotland has a way of identifying additional support needs which is quite encompassing; it includes but extends beyond a medical diagnosis or a specific identification of a special educational need. At the time of the report, over 1/3 of school-aged children in Scotland had an additional support need. That’s increased since then. I was in a school where over 50% of the pupils had an additional support need. This has been brought up in previous reviews but the issue is getting more and more complex. Obviously the COVID-19 recovery has exacerbated some things and resources are not there to fully support all learners. For me, that was one issue we had to be clear about. When it’s almost half of your demographic, it’s no longer an additional support need; it’s the need of pupils in Scotland. We had quite a lot to say about that.

“When it’s almost half of your demographic, it’s no longer an additional support need; it’s the need of pupils in Scotland.”

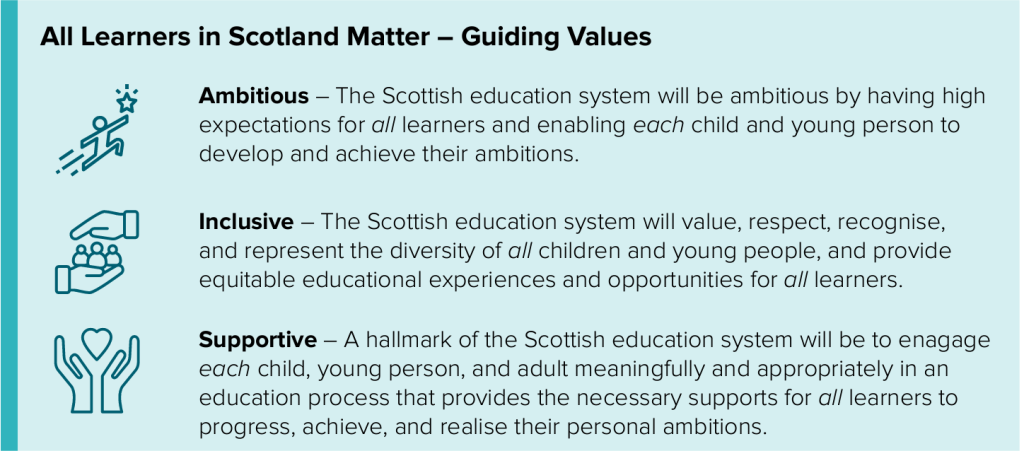

AH: We gave feedback to the Scottish Government that their core guiding principle of ‘excellence and equity’ was just not being fulfilled on the ground. There are a whole range of complex reasons for that, of course, and responsibility does not just reside within education as inequity is multi-faceted. When talking to parents and those who look after children and young people, one thing was crystal clear, that the ravages of poverty on educational progress and attainment were tangible and were getting worse. The issue of social justice runs right through the National Discussion report. The effect of poverty on the lives and life chances of existing and future generations in Scotland, like so many other countries, is the real issue to be tackled.

In many ways, the whole National Discussion was about inequities in the system, not by design but by default. Most of the anger and frustration we heard, from many groups including teachers and other educational professionals, could be attributed to some sort of injustice or inequity emanating, most usually, from a lack of resource. It was clear that everyone we spoke to wanted to do their level best for children and young people in Scotland. There was a great deal of praise for the Scottish Education system but also a real sense that more could be done. In many ways the National Discussion held a mirror up to the daily reality facing children and young people and the adults that care for and support them. There were many positive things we heard from learners, things they liked, great things about teachers and an excitement about learning. In the report, we talk about the joy of learning and the way in which teachers enthuse and encourage all learners at all levels within the system. In many ways, Scotland is a good education system aiming to be better but to make this jump, as we heard time and time again, some change needs to happen.

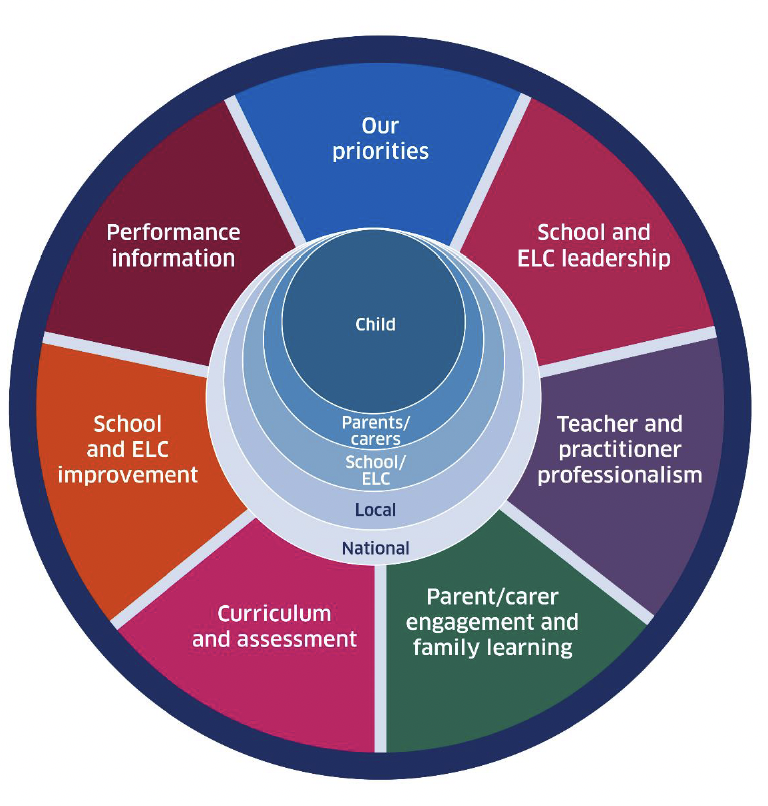

CC: Also, the title of the report is, “All Learners in Scotland Matter,” and we were asked to develop a vision. The vision is about all learners in Scotland, which sounds glib, but given what we had heard, to actually realize in practice that all learners in Scotland matter was crucial. So, Scotland’s main education priority is closing the poverty related attainment gap, which is very important. As Alma has indicated, poverty is a serious issue and children’s poverty is a very serious issue, but not all the needs we heard were about this. Some were more about physical disability, some were about mental health, some were about racial or sexual discrimination. Now these intersect, but we were saying you need to look at the full range of inequities and differential treatment.

AH: The thing that struck me most was the fact that there were so many different groups associated with a wide range of issues in education that it was almost impossible to decide who was standing for which specific issue. It was a very crowded landscape. We had the privilege, however, to go beneath the surface, and I think we have a more informed picture of Scottish education because we listened to so many diverse positions and viewpoints.

TH: This does raise the next question, which is, it’s one thing to say truth to power, but then what happens next? Are there ways in which the government has listened and is responding?

CC: The report with the vision, values, and call to action, which gets a bit more into the details of the different things that are being suggested, was released at the end of May last year. There was a parliamentary debate about the report led by the Cabinet Secretary for Education and Skills. All political parties in the Scottish Government have accepted and endorsed the National Discussion and have officially supported it. This is unusual because education is a very political priority in Scotland, so to have all party support was unusual and to have a full parliamentary debate was one way of bringing the report into the public eye. The vision from the report from the National Discussion has been accepted by the Scottish Government and now informs the “National Improvement Framework.”, which is the annual framework for educational improvement in Scotland. The calls to action are intended to inform government decisions and actions moving forward as they align strongly with priorities for attention and implementation.

One positive aspect that I find noteworthy is that the groups we’ve engaged with have embraced certain topics from the National Discussion to advance their own advocacy agendas. Professional organizations, for instance, are highlighting issues such as valuing and developing the profession, while parents are also echoing concerns we’ve addressed, such as support for early learners. This reflects the alignment with the broader national discourse, wherein groups are leveraging specific statements or discussions to push for action. Local authorities, akin to school districts, have integrated elements from the National Discussion into their strategic plans and work.

While progress has been made, it’s fair to say that we would like to see further explicit action and rapid implementation linked to the National Discussion calls to action. The challenge lies in seamlessly integrating these discussions into existing frameworks and plans. This can be particularly frustrating for parents, as they inquire about the fate of their input. We will be asked directly what happened to something a parent or other person told us directly during the National Discussion. While the calls to action are being integrated into governmental work stream, this is not a satisfactory response for people who want explicit and visible responses to their input.

AH: A couple of reflections on the follow-up. I think responding to a large and complex report based on a huge public engagement exercise is inevitably challenging. Looking at the report, you might think “where to start and what to privilege when everything is so important?“ In reality, also everything costs money. Hence it is perfectly possible that there are just too many things that need attending to in the ‘Call to Action’ section of the National Discussion Report. We accept this but we represented what we heard, faithfully and accurately.

Possibly there is a sense of disappointment that the National Discussion did not point to any one definitive thing that needed to be introduced or changed. If this had been the outcome it would have certainly been neat but also fundamentally unrepresentative of what we heard. On reflection, this public engagement approach to education reform is worthy of consideration by other education systems, primarily because it offers an alternative to the top-down processes that tend to dominate policy formation and so often fail to deliver.

As a recent Times Educational Supplement article about the National Discussion noted: “This is a model that could be built on and replicated in future reform. It is crucial that the potential here is not lost-the future of Scottish Education depends on it.”

“’This is a model that could be built on and replicated in future reform. It is crucial that the potential here is not lost-the future of Scottish Education depends on it.’”

CC: To build on that, over 38,000 people are engaged now. Yes, the scale of data was overwhelming. The range of possibilities is overwhelming. But as Alma said, our advice would be to choose one thing, choose three things. There are clearly some things that need attention. Another generation is going through our education system and there’s an argument about the system being overstretched and not wanting to make wrong decisions on reform, but we can’t leave the status quo either, we heard about urgent and needed changes. For example, workload, violence, equity, all of these things are issues which requires some change.

What came through to me was that people wanted to be heard, and they wanted to make a difference. It wasn’t a case of “please don’t change everything, we’re tired, please go away.” They actually were willing when they were asked. But that quickly turns into frustration and cynicism if you’ve taken your time and effort to engage and you don’t feel appropriate follow through has happened. While we did try to do this differently, it is one of many reviews of Scottish education. Now, the other ones are more specific about curriculum or assessment. But for some people and groups, they’ve now given their advice many times. That’s kind of a tipping point. The government needs to listen and use the evidence to inform decisions.

“People wanted to be heard, and they wanted to make a difference…. The government needs to listen use the evidence to inform decisions .”

One of the calls to action is called “Human-centered Educational Improvement”. We’re thinking about this as a new way of making educational changes. A lot of the previous reviews have ended up being very structural in terms of recommendations – abolishing organizations, introducing new qualifications. These all matter, but what we actually heard was people wanted to focus on the people: the children, the young people, the carers, the educators. For them, that was the guiding purpose. The other stuff was important, but they didn’t want another set of structural reforms. They wanted to get the focus back to people and relationships in education.

TH: Let’s delve into that further. If you had the opportunity to do this again or were advising others looking to engage in a similar process, how would you approach it differently? What additional steps would you take to steer it in the direction of being a novel process and form of support for educational change?

CC: There’s interest in Scotland in making sure this is not a one-off event, but we’ve also had international interest. There’s a team in Germany who would like to do something similar, so we’ve been talking about it. I do think the team that’s involved is crucial because it’s a huge amount of work, involving logistics, strategy, research, analysis, and communication. The individuals leading it, whether independent facilitators, senior government figures or some form of ambassadorial role, set the tone, and that matters. It’s important to encourage people from various backgrounds and experiences to lead their own discussions, aligning with our vision that these conversations would take place across different settings, with participants then submitting their insights. Having a clear and compelling question or purpose is essential; otherwise, people may struggle to understand the initiative’s intent. It’s crucial not to overwhelm with too many questions.

In hindsight, I think perhaps we asked too many questions. Don’t try to be too clever about the questions. What do you want? Why? Because people were struggling with any question that seemed complex or abstract. We were asking them to look 20 years into the future, but people were talking about what happened yesterday or what was happening on Monday. I think some of that future thinking is just difficult for people when they’re dealing with their day-to-day.

“We were asking them to look 20 years into the future, but people were talking about what happened yesterday or what was happening on Monday. I think some of that future thinking is just difficult for people when they’re dealing with their day-to-day.”

People were much more comfortable expressing challenges and concerns but articulated less suggestions for practical alternatives. So, perhaps after these large public engagements, you need a slightly different approach to reaching the next steps. As we were working on our final report, we revisited the key groups and tested out the vision and values. This involved another round of iteration to ensure that the wording and content resonated and connected with participants. Mostly, we received positive feedback, but there were some suggestions for improvement. I also think if you say you’re going to listen, you need to genuinely listen.

As independent facilitators, there’s also an expectation that we remain independent, facilitate the discussion, and present the report. But for some countries or systems, I think we should have considered advocacy and action more thoroughly – moving from presenting the report to instigating change. It’s essential to encourage people not to rely solely on the government for all changes. Some require government action, but others relate to cultural shifts within the education system or how people interact with each other. The calls to action from the National Discussion are for everyone involved in Scottish education.

“The calls to action from the National Discussion are for everyone involved in Scottish education.”

AH: In terms of additional steps, three things come to mind. The first is starting with the end in mind. I think being clearer about exactly what the end point should look like, in terms of action, would have been helpful. In other words, a deep commitment to some change that would follow the National Discussion. The second thing is about policy churn. Inevitably, things change quickly in politics and often policy attention moves on simply because that is just the way that policy works, not because it is a reflection on the nature or importance of the work undertaken.

The third thing I’d say is that the National Discussion remains a good example of flipping the system, shifting power relationships so that ideas flow from a broader base to inform policy making and shape the discourse of education reform. The National Discussion succeeded in providing a broad range of views, in that sense it was an achievement as a genuine broad-based listening exercise. It is important to see the National Discussion therefore not as an event but as on ongoing process of dialogue within the system.

“The National Discussion is a good example of flipping the system, shifting power relationships so that ideas flow from a broader base that inform policy making and shape the discourse of education reform… It is important to see the National Discussion therefore not as an event but as on ongoing process of dialogue within the system.”

TH: To me, it sounds almost like you’ve described a new and powerful process for engaging many people in sharing their concerns and hopes. But it seems like the mechanisms and routines for continuing that conversation and engaging in advocacy and decision-making at a local and national level have not been fully established yet. Can you imagine some mechanisms or routines that you would like to see put in place to help sustain the conversation and support responses that would address the priorities that surfaced?

CC: There’s a current fear, if we’re honest, in doing anything that might be unpopular or destabilizing. But the National Discussion includes the voices of a lot of people. If I were the political leader or an educational leader, there’s material there to support bringing about changes. It’s not just an idea from the government or from the civil service or from one particular interest group; there’s evidence and voices from thousands of people. The National Discussion needed resources, as we’ve discussed, but an ongoing conversation in Scotland doesn’t. Social media continues, parents’ groups continue to meet, teachers continue to meet, educational organizations continue to advocate.

To pursue transformation, some of the challenges lie in the existing established practices for example linked to the improvement framework and data requirements. However, we would encourage school and system leaders to have the courage to recognize that the status quo needs changes. While they can’t change everything, they can make a difference in their own spheres, whether it’s their classroom, organization, or local authority. I will say that there are some local authorities and schools that have embraced this mindset. It’s about instilling a cultural shift. It doesn’t mean changing everything, but it should mean changing something.

AH: My hope is that the National Discussion shows that an alternative, inclusive approach to educational change and reform is perfectly possible. Very few countries have undertaken such a discussion on education on such a large scale, so in many ways Scotland is ahead of the game. My hope is that this model of change will be embraced by other countries and that in Scotland the National Discussion continues, as a process, in some way.

TH: Is there anything else you want to add that you haven’t mentioned or anything that you learned from the process that you wanted to share at this point?

AH: I have been working in the field of educational change for over three decades and my observation is that I don’t think much has changed in terms of our approaches to reform at scale. I think we know that top-down approaches don’t always work yet there is still an over-reliance on approaches to educational change that are tightly controlled and not creative. Without question, the National Discussion was a creative approach to educational change that generated a great deal of buy-in. I think it offers an alternative approach to reform at scale but only if concrete, meaningful and informed change follows from it. If change does not happen, it is quite simply, a lost opportunity.

CC: It’s of course extremely important to engage and listen with all the formal representative groups in education, teachers, school leaders, etcetera. But by doing this in a broader sense, and we aimed our best to be inclusive and to listen, we heard different things, and we heard important things. Sometimes we hear about student voices or parent engagement, but we heard things I don’t think would have come through the same way. So, I think there are times when a genuinely public engagement matters. I wouldn’t say for something that’s very technical or specific, but this was about what we want for the future of Scottish education. I think that matters. I think that inevitably, and rightly, much of the conversation right now is about digital and artificial intelligence, but we kept hearing about people and relationships, so let’s not lose the priority importance of human-centered educational improvements as we have these other conversations.

“There are times when a genuinely public engagement matters. I wouldn’t say for something that’s very technical or specific, but this was about what we want for the future of Scottish education.”