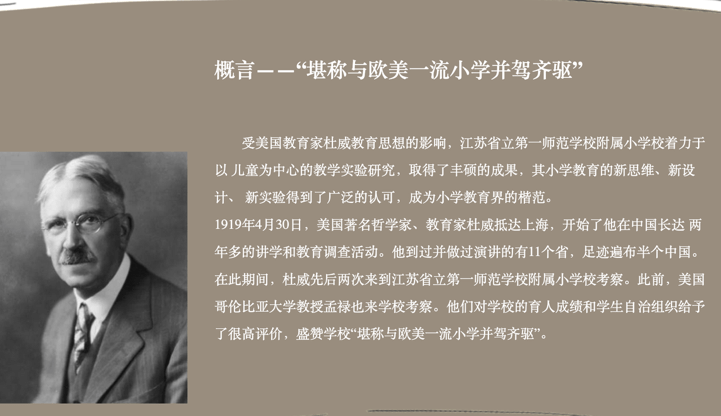

What challenges and opportunities can AI create for creating a more balanced education system? In the third post in this five-part series of reflections on his visits to innovative schools in China, Thomas Hatch describes what he learned from a visit to the Suzhou Experimental Primary School in December of 2025. This post summarizes what he took away from a forum where a group of teachers described the different ways they are using AI and the critical questions that it raises for them. The Suzhou Experimental Primary School is recognized as one of the best primary schools in China. In addition to famous graduates that include the architect I. M. Pei, that recognition builds on a long history that includes two visits from John Dewey during his visit to China that began in 1919. At the time, Dewey described the school as “the equal of first-class elementary schools in Europe and America” (“堪称与欧美一流小学并驾齐驱”). This post draws on an AI-generated transcription and translation of the conversation and benefitted from the comments of Zhenyang Yu and the support of Jianhua Ze and colleagues from the World Association for Creativity (WAFC) who arranged the visit.

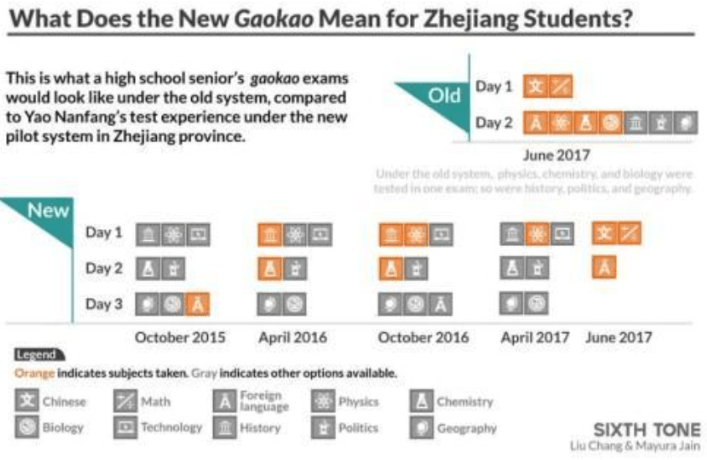

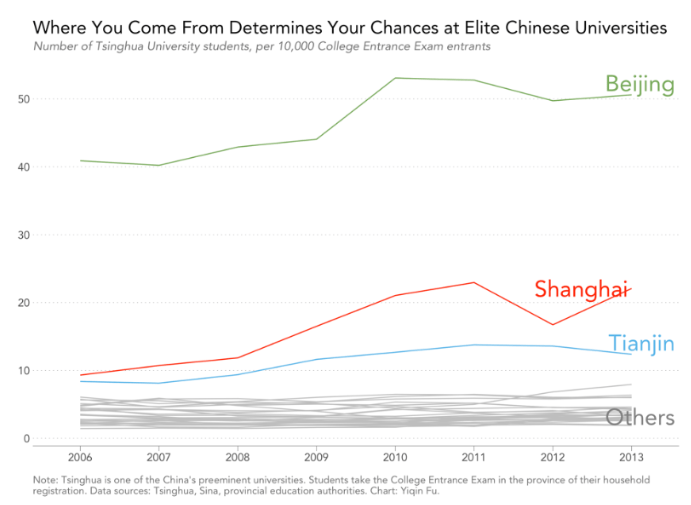

The first post in this series described how some innovative schools in China are creating the time and space for more student-centered learning experiences, and the second post discussed how the Chinese education system has changed over the past 30 years. Future posts will discuss the growth of academic pressure as well as the technological and societal developments that may allow for the emergence of a more balanced education system. For previous IEN posts on educational change in China see “Boundless Learning in an Early Childhood Center in Shenzen, China;” ”Supporting healthy development of rural children in China: The Sunshine Kindergartens of the Beijing Western Sunshine Rural Development Foundation;” The Recent Development of Innovative Schools in China – An Interview with Zhe Zhang (Part 1& Part 2);” “The Desire for Innovation is Always There: A Conversation with Yong Zhao on the Evolution of the Chinese Education System (Part 1& Part 2);” “Beyond Fear: Yinuo Li On What It Takes To Create New Schools (Part 1);” “Everyone is a volcano: Yinuo Li On What It Takes To Create A New School (Part 2);” “Surprise, Controversy, and the “Double Reduction Policy” in China;” ”Launching a New School in China: An Interview with Wen Chen from Moonshot Academy;” and ”New Gaokao in Zhejiang China: Carrying on with Challenges.”

A warm welcome and an unexpected surprise awaited around every corner of my school visits in China. This past December, those surprises revealed what seemed to be a sudden explosion in the uses and discussions of AI in education. There was an elaborate AI lab at the Shanghai Shangde Experimental School (along with a drone arena and a robotics track); a showcase of sophisticated “kits” for incorporating AI into hands-on activities at the Nanjing PD Center; and a series of presentations at a conference on hands-on learning organized by the World Association for Creativity that highlighted the importance of the teachers’ role in AI.

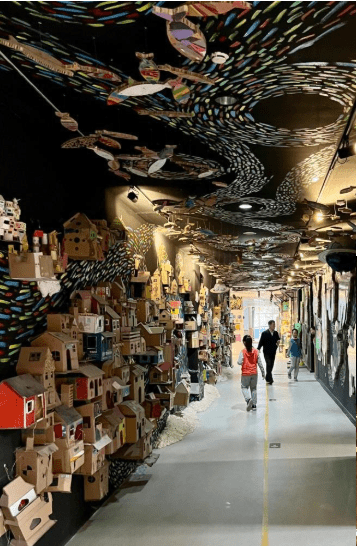

At the Suzhou Experimental Primary School, I was not thinking about AI at all when the leader from the school, Ge Daidan, and several English teachers, Zhao Hong, and Ye Qiujiao, took me on a tour of the school and led me through the school’s own museum. The many rooms and exhibitions of that museum chronicled John Dewey’s visits to the school in 1919 as well as the school’s growth and development since that time. But the surprise came when I went up the stairs and turned a corner, only to discover a small crowd of about thirty people waiting for me in a well-appointed meeting room. As soon as I was seated at the head of a conference table, six teachers, arranged in a semi-circle in front of a giant screen, launched into a set of carefully prepared and thought-provoking presentations about how they were working with and reflecting on their uses of AI throughout the school. Those presentations offered specific examples of how AI can already be put to work in a wide range of classes – including kindergarten, Chinese, English, Math, and Art – to help create more powerful, interactive, and student-centered learning opportunities in China and around the world. Yet at the same time, the teachers raised fundamental questions about the role of AI in education in general, the specific role of teachers in mediating AI use, and what distinguishes human contributions from those of AI.

Questions and Issues for AI in schools

The moderator, Huang Fei, began the forum by asking a question from a paper by Professor Wu Kangning of Nanjing Normal University – “What challenges does AI bring to education?” Faced with the waves of new developments, she asked “Should we embrace AI or wait and see? Should we lead or follow? How will the role of teachers, the form of the classroom, and the ecology of education be reshaped?”

“Should we embrace AI or wait and see? Should we lead or follow? How will the role of teachers, the form of classroom and the ecology of education be reshaped?”

Although it was impossible to capture all the issues that were raised throughout the rest of the forum, key questions included:

- Is it too early to be trying to incorporate AI into our work with students?

- Will AI provide assistance or will it become a crutch?

- How can AI save time, foster creativity, and support innovation, and strengthen teachers’ relationships with their students rather than weaken them?

- Will AI help students and teachers to extend and develop their capacities rather than undermine them?

- How can AI foster students and teacher’s creativity rather than stifle it?

- How can AI enhance teachers and students’ motivation rather than diminish it?

- What is the teachers’ role when AI is being used?

- Will AI lead to a focus on precision and efficiency that may interfere with the spiritual growth of students?

- How can we use AI to ignite the mind and heart?

- How can future education balance AI data-driven insights with humanistic judgment?

As the moderator noted, these questions illustrate that “challenges and opportunities are often two sides of the same coin,” tensions that are unlikely to have a simple resolution, but that will require regular reflection.

[T]hese questions illustrate that challenges and opportunities are often two sides of the same coin, tensions that are unlikely to have a simple resolution, but that will require regular reflection

AI across subjects and classrooms

Following the opening remarks, the other five panelists offered a series of specific examples that demonstrated how the school is attempting to find a balance that enables students and teachers to use AI to extend their abilities without increasing the incentives and creating the conditions that discourage them from deepening their learning and exercising their agency and creativity.

Kindergarten, Ms. Sheng:

AI acts as a “good helper” in kindergarten by generating a growth record for each child, based on the teachers’ observations and other data. In turn, AI can use this data to generate lesson plans and personalize growth plans which can save teachers time and enable them to focus on developing their relationships with their students.

As one example, they are using commercially produced software to help record students’ read-alouds,” and to use AI to track students’ growth in fluency, integrity, and accuracy. (For comparison to uses of AI in the US see “AI Tutors Are Now Common in Early Reading Instruction. Do They Actually Work?). When they identify students who are hesitant and reluctant in reading and speaking aloud, they can also use AI to create interactive picture books that match each child’s interests and skill level. By reducing the demands of the interactive dialogues on pronunciation, ideally, they can increase a child’s willingness to speak and express themselves.

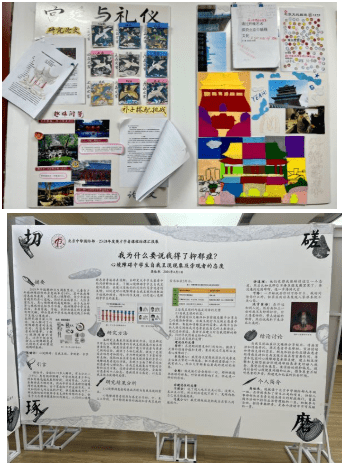

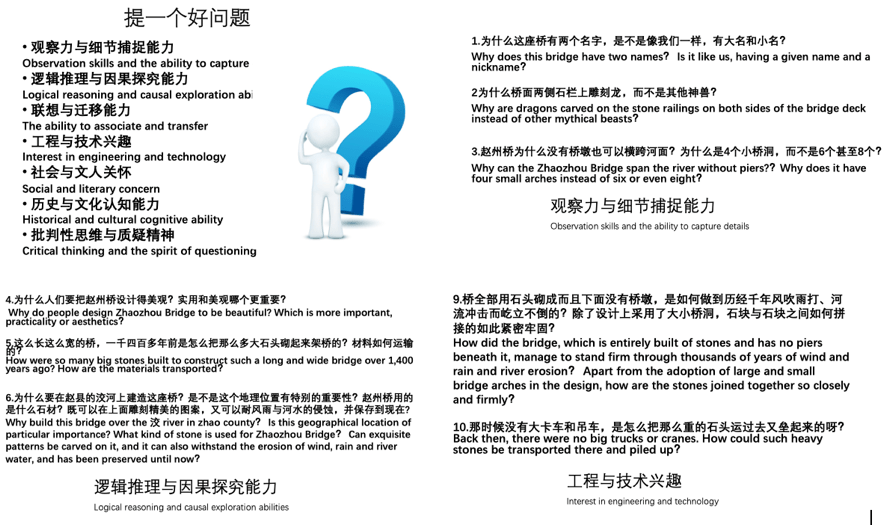

Chinese, Ms. Huang:

AI has helped teachers shift from answering questions to generating them. In the past, teachers assessed comprehension by asking students to answer questions about what they read about in historical, scientific and cultural texts. But now, they have shifted to inviting students to share their own questions, and teachers then use AI to analyze the students’ questions and to build their curriculum around them. As Ms. Huang put it: “Every good question is a seed of creation” and a window into the students’ interests, their observational abilities, and their logical reasoning. Reading a text about achievements in science, technology, and engineering, like the Zhaozhou Bridge, can lead to questions that help make visible the “germination of scientific thinking.”

“Every good question Is a seed of creation.”

Art, Ms. Wang:

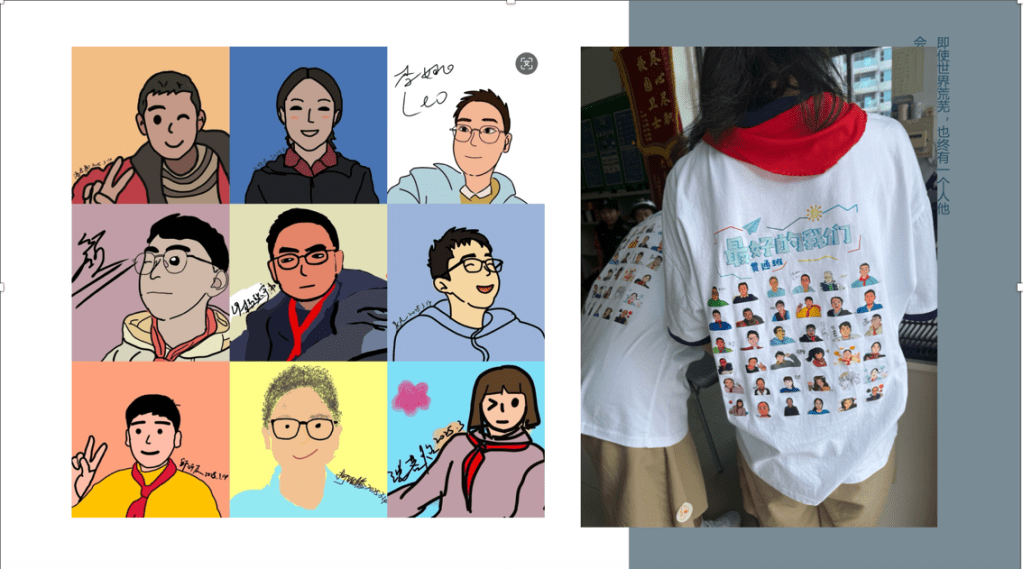

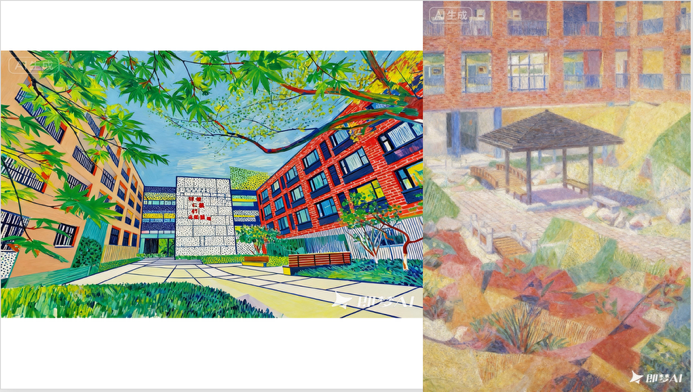

AI has “injected a new vitality into our primary school art class,” Ms. Wang explained as she chronicled how the teachers are helping students to use AI to expand their artworks and designs in a variety of ways, including:

- Making drawings on tablets that can then be printed on graduation t-shirts or turned into stop-motion animation.

- Using AI to explore what paintings of objects like their school campus might look like if they were painted by different artists or in different artistic periods as a way to develop students’ understanding of different artistic styles.

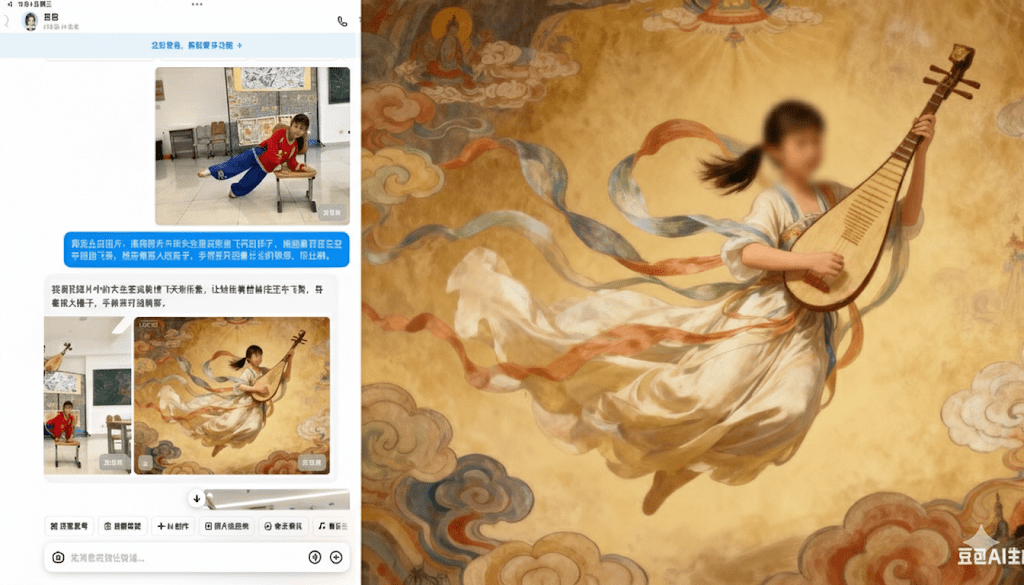

- Giving students opportunities to place themselves in ancient paintings to enhance their historical and cultural understanding of art forms like Dunhuang Feitian dance.

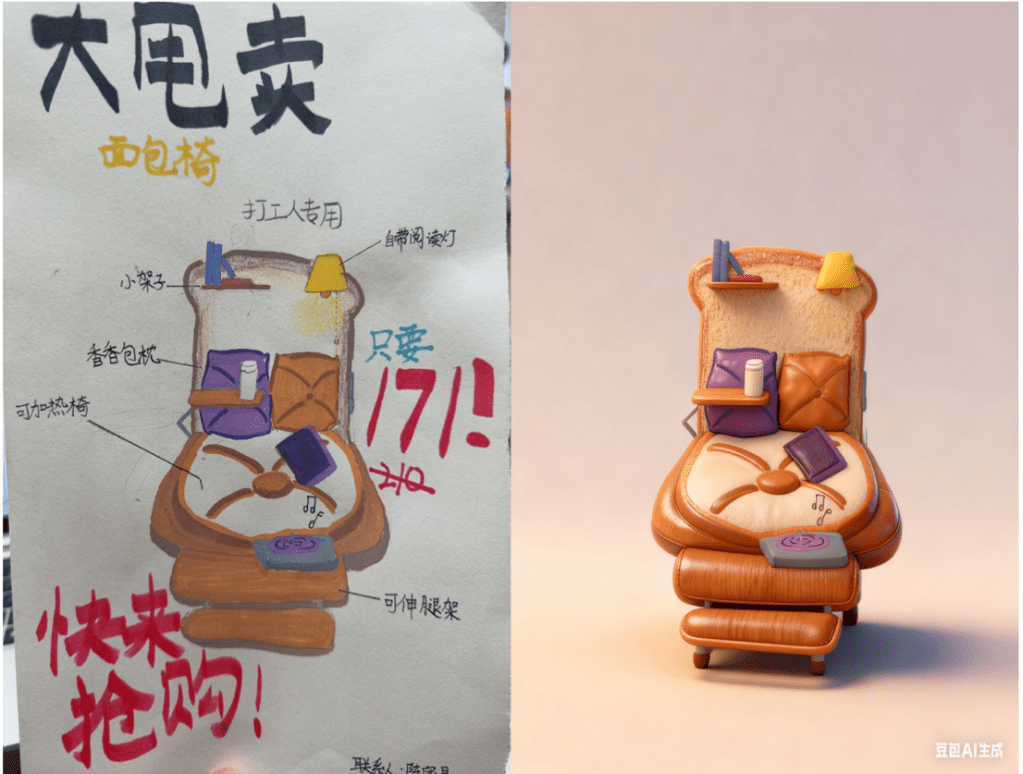

- Developing students’ designs and design abilities by using AI as an assistant to render their drawings in 3-D, enabling them to envision whether their design for an object like a chair would support someone’s weight or collapse to the ground.

- Building a virtual exhibition hall where the students can display their paintings and sculptures, and parents and friends can view and comment on them.

Yet, at the same time that Ms. Wang highlighted these artistic possibilities, she wondered: with the ease of generating finished products, will students become lazy? She concluded with a metaphor of hope: “I have always thought that AI is a museum that helps us find inspiration, not a print shop that gives you finished products directly.”

Math, Ms. Xu:

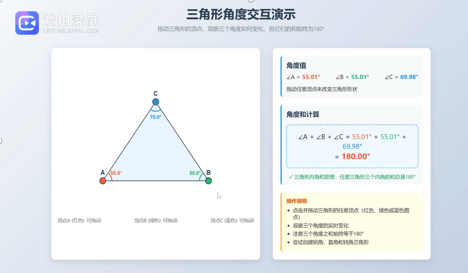

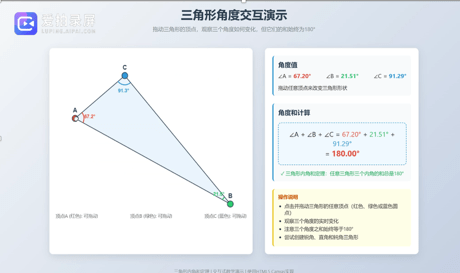

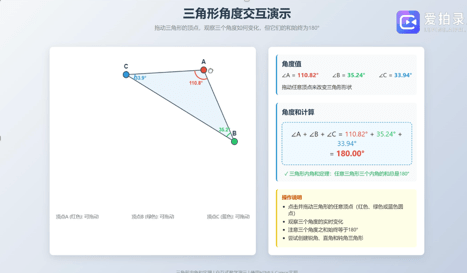

Teachers are using AI to help them create interactive and collaborative activities. For instance, to help students understand that the sum of the interior angles of a triangle is always 180 degrees – a fundamental geometric principle – the teachers are usingAI to produce a series of interactive demonstrations. Groups of students can manipulate the vertices of triangles of different shapes, discuss the results, and make comparisons. AI can record the conversations and help teachers identify key words and misconceptions that can inform their subsequent instruction.

They envision as well using AI to increase the precision and effectiveness of their teaching. They can imagine assigning students exercises to complete on digital devices and developing AI agents that can identify mistakes and then link to corresponding explanation videos and examples to work on.

Data-use, Ms. Hu:

In addition to using different AI applications to collect subject-specific data within particular classes, the school also uses AI to help them look for trends and patterns in data across the school. These analyses make it possible for them to quickly visualize growth trends and patterns in in five different areas including physical fitness, effort, ethics, and academics.

Teachers can also use AI to help them adjust their instruction to meet the needs of different classes. For instance, teachers can compare students’ English homework to see that one class may be struggling with pronunciation while another may be more be particularly advanced in vocabulary, leading a teacher to emphasize activities for sound discrimination for the first class and to introduce new content to the second. Ms. Hu concluded by noting that “AI can give us a clear diagnostic map. But a prescription…is our teacher’s duty and wisdom.”

Hope and concerns for the future

Across these examples, I was particularly struck by the way teachers addressed the common concern that AI could transform teachers’ roles and the effect it might have on the teacher-student relationship. As Ms. Sheng articulated it, will the use of AI help to deepen teachers’ expertise and help to strengthen the relationships between teachers and students? Or will it interfere with teacher-child interactions and violate the essence of their child-centered educational approach?

“[W]ill the use of AI help to deepen teachers’ expertise and enable them strengthen their relationships with their students, or will it interfere with teacher-child interactions and violate the essence of child-centered educational approach?”

In response, the teachers emphasized that AI can’t replace the emotional links between people, and that teachers need to be able to pay attention to the more emotional aspects of children lives that may not be captured in the notes, observations, and other data that AI relies on. “AI can create beautiful paintings,” Ms. Wang, the art teacher noted, “but it can’t read the crooked little happiness in the sun painted by children. AI can’t replace the teacher who squats down to ask the child ‘Why are the clouds painted pink today?’”

The presentations concluded with each teacher sharing, with hope and confidence, that they could find a balance that takes advantage of the potential of AI while enhancing the opportunities for teachers to draw on their emotional experience and humanity. As one put it, “I think as a teacher, the real wisdom lies in using the computing power of AI to liberate the teacher’s mind.”

The moderator added, that by following the development of the students and constantly adjusting teachers’ practice and cognition of teaching, “we will be able to gradually adapt to this educational change… It is really good to let AI be good at its skills and let the teacher keep his heart. Cultivate each child’s unique light with educational wisdom. Let’s guard the children’s unique light together.”

“It is really good to let AI be good at its skills and let the teacher keep his heart. Cultivate each child’s unique light with educational wisdom. Let’s guard the children’s unique light together.”

What does education demand of AI and its developers?

I don’t have any idea how many other educators in China are using AI in these ways, but I have no doubt that these are the kinds of questions we should all be asking: How can we find a balance that takes advantage of AI without succumbing to it? How can we enable students and teachers to use AI to extend their abilities without discouraging the from exercising their agency, deepening their learning, and developing their creativity?

As Dewey suggested, education is not preparation for life; it is life itself. And in that spirit, we need to go beyond arguments about whether and how to stop children from using AI to ask, as these teachers are doing, how we can use AI powerfully, ethically, equitably?

At the same time, even if we embrace Dewey’s philosophy and strive to engage students in real world activities, we do so with care and guidance. We can encourage students to explore the world beyond their classrooms, venture into the forest or cultivate a garden, but that does not mean that we leave them to play in a patch of poison ivy. Reflecting the concerns about the potential harms of AI use in schools, the Chinese government has already developed guidelines designed to support ethical and appropriate uses of generative AI and to address potential harms. According to these guidelines, “primary school students are not allowed to independently use open-ended AI content generators, which could allow them to use AI to do their assignments for them. Middle school students may explore the logical structure of AI-generated content, while high school students are permitted to engage in inquiry-based learning that involves understanding AI’s technical principles.” At the end of 2025, the Chinese Cyberspace Administration also released draft regulations that would restrict AI chatbots from influencing human emotions in ways to could contribute to self-harm. (In contrast, as Max Tegmark, MIT physicist and founder of the Future of Life Institute, points out that the US government has more regulations on sandwiches and food safety than on a technology that could sell AI girlfriends to 11-years olds and might develop a “superintelligence” capable of overthrowing the government itself.)

Like the teachers at the Suzhou Experimental Primary School, we have to keep in mind both the possibilities for learning and the dangers that AI brings. It can analyze huge amounts of data and identify patterns on a large scale. It can provide greater precision and efficiency in some tasks, but it can also be addictive, misleading, and biased. It works, in a sense, on the past, on the data that has been generated and made accessible, but lacks – for now at least – as the teachers pointed out, human emotion and imagination. That means that the greatest benefits of AI may come when educators are a crucial part of children’s relationships with AI and other technologies; when we equip teachers with the tools of AI rather than relying on the ghost in the machine; when we use AI to help us imagine new and more equitable educational arrangements, new opportunities for learning and teaching that are not trapped in our past experience. As Cornelia Walther expressed it: “We must double down on the human element. The better we become at being human, at communicating, at reasoning, and at envisioning, the more the mirror of AI will reflect back greatness.”

The examples these teachers shared point to some of the many ways that AI and other technologies may open the doors to more interactive, student-centered activities in China and other parts of the world. But will they? In the end, I came back to the moderator’s initial questions that launched the entire forum: What is the role of teachers, students, and schools in artificial intelligence? Should we lead, or should we follow? These presentations taught me that teachers and students should be leading the way. To make that possible, rather than asking “what challenges does AI bring to education?” We need to bring the challenges of education to AI and demand a thoughtful and ethical response.

“These presentations taught me that teachers and students should be leading the way. To make that possible, rather than asking “what challenges does AI bring to education?” We need to bring the challenges of education to AI.”

Teachers and students should bring their questions and ideas to artificial intelligence. We need to tell the AI designers and developers what education demands; what schools, educators and students need, and what problems they face. By truly challenging the designers and artificial intelligence itself, perhaps we can make AI a tool that expands our educational imagination.

Next Week: Could concerns about the academic pressure on students in China lead to real changes in conventional schooling? Stability & change in the education system in China (Part 4)