In this month’s Lead the Change (LtC) interview Nicole Patterson shares her experiences as a principal working to create equitable opportunities and sustain educational change for her students. Patterson recently completed her Doctoral degree in Educational Leadership at Saint Joseph’s University. She has worked as a teacher, instructional coach, assistant principal, and is currently a principal — all within inner-city communities.The LtC series is produced by Alex Lamb and colleagues from the Educational Change Special Interest Group of the American Educational Research Association. A pdf of the fully formatted interview is available on the LtC website.

Lead the Change (LtC): The 2024 AERA theme is “Dismantling Racial Injustice and Constructing Educational Possibilities: A Call to Action.” This theme charges researchers and practitioners with confronting racial injustice directly while imagining new possibilities for liberation. The call urges scholars to look critically at our global past and look with hope and radicalism towards the future of education. What specific responsibility do educational change scholars have in this space? What steps are you taking to heed this call?

Nicole Patterson: Educational change scholars have a responsibility to ensure they operate with a sense of urgency as they advocate for sustainable change for those entrusted in our care. In short, this looks like educational scholars staying updated on the latest research on racial injustices, applying these findings to their everyday work, committing to the feeling of discomfort, and understanding change is often on the other side of this feeling.

Nicole Patterson

My latest research titled, Taking a Knee (Patterson, 2022) is connected to the 2024 AERA theme of “Dismantling Racial Injustice and Constructing Educational Possibilities: A Call to Action” by examining the level of cultural competence and awareness of structural inequities educators used in their daily teaching practice of Black and Brown students.

“Taking a Knee” is a phrase with various meanings. To some, taking a knee was perceived as a disrespectful act to the flag of the United States of America. To some, taking a knee was a stand against an American history of oppression and injustice. Forothers, the phrase represents the lack of regard for human life evidenced by the Minneapolis police officer’s murder of George Floyd. The difference between these aforementioned perspectivesis that oftentimes when Black and Brown people take a stand to uplift and overcome the plight and oppression that they’ve experienced for over 400 years by promoting their natural given birth right to live without oppression and within a life full of joy, opportunities, and advancement, the intent is misconstrued. Individuals without awareness of the plight of Black and Brown people, in turn, can intentionally or unintentionally use the same behavior of continuous oppression to crucify the dreams and ambitions of Black and Brown people, and this process can be defined as cognitive dissonance.

“Overt and covert acts of violence and disservice represent the need for increased levels of cultural competence for all educators.”

For me “Taking a Knee” represents the consistent murder of Black and Brown people through police brutality and how such events mirror the treatment of Black and Brown children in the United States’ educational system. We are currently amid two global pandemics, the COVID-19 pandemic and the pandemic of Social Injustice. The pandemic of Social Injustice in America begins in 1619 when chains were worn instead of masks and the only viable vaccine was the risk of traveling the underground railroad with Harriet Tubman. We see evidence of this pandemic in the field of education when educators unintentionally and intentionally “kneel” on the necks of Black and Brown students, sucking the breath of air, knowledge, passion, and opportunity from Black and Brown youth. These overt and covert acts of violence and disservice represent the need for increased levels of cultural competence for all educators including educators who mean well but show levels of cognitive dissonance by participating in actions they previously stated they would not. Educators need to engage in reflectionand engage in the process of unlearning and relearning or dismantling and constructing a system full of possibilities.

LtC: As a principal and scholar, you bridge research and practice through your work in both spheres. What are some of the major lessons the field of Educational Change can learn from your work and experience?

NP: It is truly a blessing to serve in the capacity as school principal and scholar. I truly did not understand the blessing until I was within my dissertation work. I felt such liberation in the access to relevant information to inform my practice as an educator. Lessons I have acquired along the way are:

● Power of relationships

● Advocacy

● Consistent Action

Relationships have been the greatest lesson in this sphere. Meeting like-minded individuals and others that challenge perspectives has been an asset to my overall paradigm in education. These relationships have afforded me the privilege to get into the spaces and places of those who came before me. These relationships have also allowed me to lift those up that come after me to bring them into the same spaces and places as I was. I often say, “relationships are worth more than money.” The power of a relationship can take you so much further than any dollar amount. My professional and personal relationships have allowed me to develop into the scholar- practitioner that I am today. I will continue to reach back and support those as was done for me.

“Each day as scholar-practitioners we are either moving closer to a more equitable system or further away.”

As a scholar-practitioner I have found my voice as an advocate in my field. Understanding and having the level of discernment on when and what to advocate for is paramount. This season and growth in advocacy that did not occur until I realized the power and privilege I have as a Black female educator. In other words, although I have intersections of race and gender, I still have a privilege regarding access to educational advancement and financial means to attain schooling. Understanding this, I use my education to empower and educate others. On a daily basis, the power of advocacy is a lesson learned and utilized to ensure I continue to pave the way for the students and families that are so deserving of an educational and life experience that is oftentimes not equitable.

Last, consistent action! One of my favorite quotes is, “What you do every day matters more than what you do every once in a while.” This quote applies to all areas of life, and while I typically reference this regarding my health and fitness journey, these words hold true in service in the educational field. Each day as scholar-practitioners we are either moving closer to a more equitable system or further away; I do not believe that anything stays the same. With this mindset, I am committed to ensuring consistency in all that I do for educational advancement. I am also cognizant of those who are constantly watching what I do and say. I need to model leadership to empower those in my care.

“Each day as scholar- practitioners we are either moving closer to a more equitable system or further away.”

LtC: In some of your recent work, you investigate how teachers and administrators lead for learning and cultural proficiency during times of disruption. How might your findings help inform our understanding of professional development, educational justice, and educational change more broadly?

NP: My research allowed the space for educators to evaluate their sense of cultural competency on a pre-existing Cultural Competence Self-Assessment for Teachers (Adapted from Lindsey, Robins & Terrell [2009] Cultural Proficiency: A Manual for School Leaders). This survey paired teacher voices to the interpretation of their score to their daily instructional pedagogy. Once the teacher was provided their numerical cultural competence score, the teacher was able to answer a series of questions to bring life to that number. Their responses were able to transition a number to words and experience of current teaching practice based upon their belief systems and lived experiences. The findings and lived experiences display that there is a clear need for educators to be aware of their level of cultural competence and differences with those they interact with. My recent work reviewed cultural competence in the context of three structural inequities: healthcare, housing, and education and all three of these structural inequities show the need for cultural competence of educators and individuals.

The implications for practice of school leaders and classroom teachers are as follows:

- use cultural competence as an umbrella for the development of teachers,

- provide consistent relationship building opportunities,

- fund programs focused on financial literacy and entrepreneurship to reach diverse populations of post-secondary student interest

- use embedded/required instructional materials that reflect student cultures and address current/future structural inequities that will mutate from current ones

- stay up to date on the digital world and provide students with needed resources

- mentor teachers in the field to address and develop understanding of their bias/feelings,

- codify a process to continue the work of educators self-assessing their cultural competence and awareness of structural inequities.

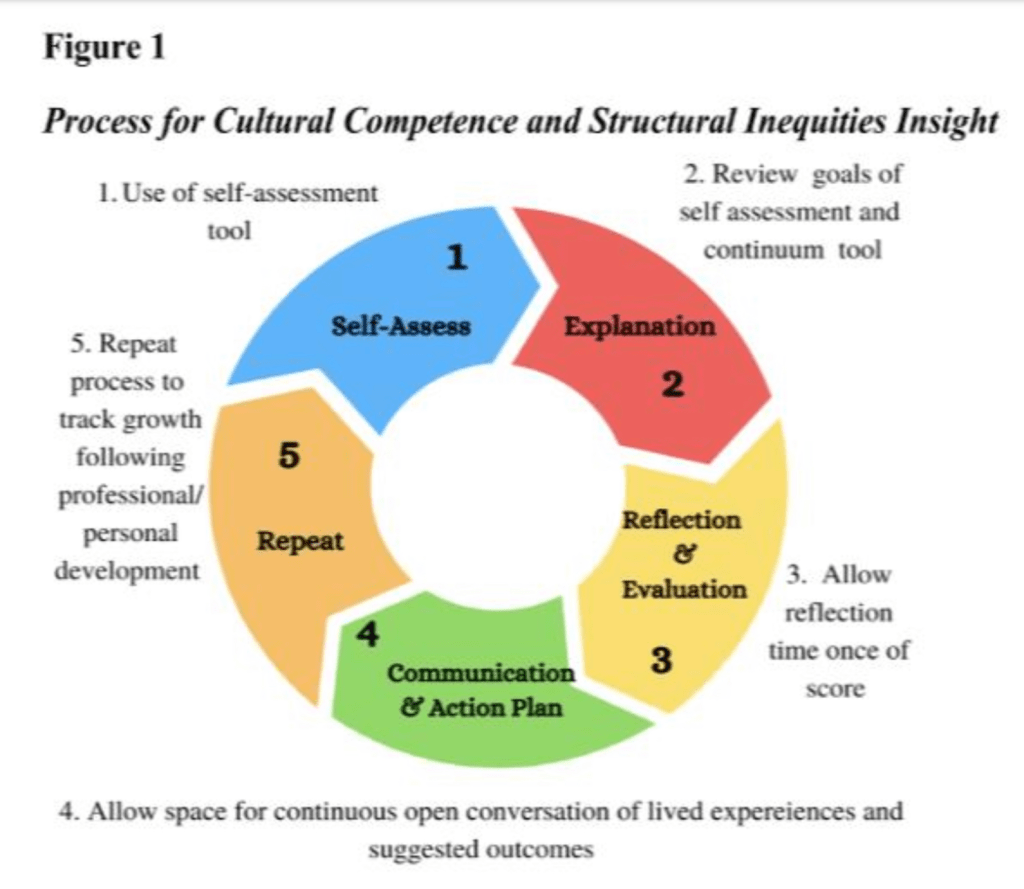

Through the findings of this work, a new process emerged that will assist educators, researchers, and students to gain an understanding of their cultural competence level and awareness of structural inequities.

This process of authentic self-assessment must takeplace for sustainable change within the educational system. This process allows educators to self-assess where they currently stand with cultural competence and structural inequities and where they think they can continue to grow and develop to make a difference through their instructional practice.

LtC: Educational Change expects those engaged in and with schools, schooling, and school systems to spearhead deep and often difficult transformation. How might those in the field of Educational Change best support these individuals and groups through these processes?

NP: Prior to supporting those who are in our care, we have to first understand and evaluate the change we are asked to spearhead and transform. Individuals in our care are in an organizational structure. It is important that teachers use this self-assessment on a continuous basis and that reflection take place at all levels to enact sustainable change. Connected to self-assessment, there must be collaboration and support systems for leaders facilitating these transformation efforts. Leaders are chameleons, and we must adapt to the needs of those we support but also use wisdom in the supports we are in need of. At times, support for leaders can be as simple and impactful as a listening ear, mentorship, and self-care,to name a few examples.

Expectations, accountability, and support are the key ingredients to needed educational change of academic and life outcomes for marginalized communities. Additionally, in order to evoke change we must include those whom the change will impact in the conversation. I often think of the saying, “nothing for me, without me.” Courageous conversations must happen at the individual and group level to ensure we are uplifting the voices of those who are involved in the change process. Everyone wants to be heard. Everyone also wants to be a part of something bigger than themselves. This can be achieved through transparency, consistent communication, and partnership during the transformational process.

LtC: Where do you perceive the field of Educational Change is going? What excites you about Educational Change now and in the future?

NP: Hope is amazing and the strongest thing to hold on to! I hope that with the rise of advocacy for cultural competence and access to relevant research, the field of education will truly become a space that benefits all the children we are blessed to serve. I am excited and encouraged by the youth! Working with such brilliant, bold, and brave students on a daily basis excites and inspires me to continue to work for educational change. The innovation, creativity, and relentlessness of our youth is a joy to experience as an educator and leader. I am encouraged by the advocacy I see young people engage in, by the multiple ways success is defined for them, and the no fear mindset that allows them to go for the goals they desire without a fear of failure. I am encouraged that as current scholar-practitioners we can contribute to the future success of students by keeping an open mind and holding onto hope. Hope is one of the most powerful things this world has to offer. Maintaining a growth mindset is needed to experience the true value of hope and dealing this hope to others.

I foresee continuous growth in the areas of educational technology. I am curious to see how artificial intelligence will continue to influence education. Currently, there are several systems that are being used by scholar-practitioners and students regarding artificial intelligence. I can only hope that as the times continue to change, schools will be ahead of the curve by providing opportunities and spaces to educate students and educators on how to best use these various technologies. I hope to see a major change in the mandates regarding curriculum and instruction to focus on financial literacy requirements, fostering entrepreneurship, courses in social emotional well-being, and courses that teach conflict resolution/self-regulation. These courses are especially imperative in Black and Brown communities where we see and experience tragedy due to gun violence on a daily basis.

Last, at the policy level, I hope to see change connected to continuous efforts to encourage and uplift the Black vote. These are the views of the silent majority and reflect the importance of the future of elections for us and our children. I am fully aware that this process is not an immediate one and will take strategic and intentional advocacy, collaboration, and resistance. I am also fully aware that the students, families, and individuals for whom we continue this heart work, will bring about a promising future for those that come after them.

References:

Guerra, P. L., & Wubbena, Z. C. (2017). Teacher beliefs and classroom practices cognitive dissonance in high stakes test-influenced environments. Issues in Teacher Education, 26(1), 35-51.

Lindsey, R. B., Robins, K. N., & Terrell, R. D. (2009). Cultural proficiency: A manual for school leaders (3rd ed.). Corwin Press

McGrath, A. (2020). Bringing cognitive dissonance theory into the scholarship of teaching and learning: Topics and questions in need of investigation. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 6(1), 84-90. 10.1037/stl0000168

Patterson, N. (2022). Taking a knee: A mixed methods study evaluating awareness of structural inequities and levels of cultural competence of middle school in-service teachers of Black and Brown students (Publication No. 28967538) [Doctoral dissertation, Saint Joseph’s University]. Saint Joseph’s University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing

The Journal of Educational Change

The Journal of Educational Change