This week, IEN’s managing editor Sarah Etzel continues a scan of recent news articles and research on post-pandemic developments in the teaching profession. In part two of the post, Etzel describes some of the initiatives to use technology to help to free-up time for teachers by reorganizing staffing and scheduling. Part one explored innovations in blended and remote teacher professional development models and the use of AI to provide feedback to teachers.

What’s happened to teachers in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic? On the one hand, in the US teacher vacancies appear to have grown substantially. One report released in the fall of 2023 showed 55,000 vacant teaching positions, an increase from 36,000 the previous year. On top of that, the report found that 270,000 teachers – almost 9% of the entire teaching force – are “underqualified,” either lacking full certification or teaching in a subject in which they are not certified. The National Center for Education Statistics also revealed that 86% of K-12 schools reported problems hiring new teachers in advance of the 2023-24 school year, and almost half of all public schools describing themselves as “understaffed.” On the other hand, the pandemic helped to stimulate experiments with new models for staffing and with virtual teachers that might help to address teacher shortages.

Staffing Changes: Unconventional Teaching Roles

Whether in-person or virtual, a small set of schools and organizations around the US are exploring what alternative teaching and staffing models for schools could look like. A report from FutureEd focusing on pandemic-inspired staffing strategies, for example, highlights the benefits of some co-teaching, team teaching, and mentor teaching models. Public Impact, working with a network of over 300 schools, has pioneered models designed to use teacher teams to enable teachers who have shown their effectiveness to reach more students. These “multi-classroom” leaders teach part-time and also lead small, collaborative teams of other teachers, paraprofessionals, and intern teachers in the same grade or subject. Cadence extends the reach of effective teachers by developing a national team of mentor teachers who deliver online lessons for a group of partner schools across the US. The teachers in the partner schools both learn from the mentor models and they can incorporate the lessons into the work with their own students. As Steven Wilson, a co-founder of Cadence, puts it: “It’s like being able to sit in the back of the room of the best teacher in the building for weeks at a time and see his or her moves and adapt them and make them your own.”

The FutureED report also emphasizes the potential of flexible class sizes, time blocks, and instructional cycles that allow for teachers to work with smaller groups of students outside of traditional grade-level and schedule constraints. As an example, the report highlights a particularly unusual approach from Kairos Academies in St. Louis that developed a seven-week schedule in which students attend school for five weeks, followed by two weeks off; staff have one week off, but use the other week to review data and plan for the next cycle. The report quotes, Gavin Schiffres, Kairos founder and CEO, describing what he sees as the advantages of the cycles; “With the cycle model, we operate in sprints, much like the technology industry. In a traditional calendar, you have kids in the building for such long stretches that as soon as there’s a break, everyone just wants to crash.”

“We operate in sprints, much like the technology industry. In a traditional calendar, you have kids in the building for such long stretches that as soon as there’s a break, everyone just wants to crash.”

Drawing on interviews with a small group of leaders from six districts involved in staffing experiments, the Center on Reinventing Public Education issued a report on how unconventional teaching roles could help to make the profession more sustainable and increase teacher satisfaction in the process. Some of these roles include:

- Lead teacher: An individual who mentors a team of teachers (across content areas or grade levels) by developing curricula and co-teaching as necessary

- Empowered teacher: An individual who supports with school-level policies and sets learning targets

- Team teacher: An individual who teaches a large group of students (50-80) in collaboration with two to four other teachers

- Community learning guide: An individual who works with a group of educators and their students to create experiences grounded in students’ wider environment, community, or culture.

- Solo learning guide: An individual who independently teaches a small group students (5-15) in school or home contexts

- Technical guide: An individual who leverages subject area expertise (e.g. robotics, architecture) to provide curriculum support and work with small groups of students

According to the report, teachers in these roles shared that they experienced less stress and felt more motivated; working in diverse or team settings, teachers were able to share responsibilities, learn from each other, and feel connected to the purpose of teaching. Despite the potential, a review of the CRPE report from the National Education Policy Center cautions that it is too early to tell whether these kinds of staffing changes could be scaled effectively or whether they would have the desired impact.

In order to address the shortage of teachers and support those that are in place, some schools in the US have also introduced models to support paraprofessionals to gain teaching credentials and become licensed teachers, while others have created pipelines for substitute teachers to gain teacher certifications. Beyond the US, organizations such as GPE KIX and UNICEF have been pioneering child-to-child teaching models, in which older students support the education of pre-primary learners, in areas where there are not enough teachers available (for past IEN coverage of peer-to-peer tutoring approaches, see: Education reform in Mexico, An interview with Dr. Santiago Rincón-Gallardo, and Bringing Effective Instructional Innovation to Scale through Social Movement in Mexico and Colombia).

Virtual teachers for in-person students

Along with developing new virtual and hybrid approaches for students to learn, during and after the pandemic, reports also note that some districts are spending millions of dollars on virtual teachers to fill-in when they can’t find the personnel they need in their local area. Among these, districts in Little Rock, Arkansas, Charleston County, South Carolina, San Jose, California, and Milwaukee Wisconsin have contracted with companies such as Elevate K-12, Coursemojo, and Proximity Learning to address their teacher vacancies and to provide virtual instructors who zoom into their classes. These companies employ fully certified virtual teachers who provide “synchronized learning services” in a range of subjects. The virtual teachers interact with students completely through the online platforms, with, in some cases, in-person supervision provided by paraprofessionals or long-term substitute teachers.

Elevate-K12’s model of “live teaching”, The 74

The benefits and drawbacks of these approaches are also being debated in the press. For some, these virtual options provide an alternative to other “quick fix” solutions that have been used to fill empty classrooms in the past, including hiring uncertified teachers, incentivizing military veterans to join the teaching force, or removing some degree requirements. According to the CEO of a San Jose charter school network that contracts with Coursemojo, this situation is not ideal, “but until we really, radically change the education profession here in the United States, we’re going to be looking at solutions like this.” Catherine Schumacher, Executive Director of Public Education Partners stated the importance of not shaming “districts for doing the absolute best they can do to get qualified teachers,” especially in a climate where “we have systematically underpaid…educators for years.”

Other advocates argue that the subjects virtual teachers are teaching have historically been hard to fill, meaning many students did not have access to these educational opportunities, particularly in low-resource school districts. As the Milwaukee Public Schools talent management director put it: “when we talk equity and access, I want to ensure that if my students want to take pre-calc, if they want chemistry, if they want physics, that they have the opportunity to do so.”

The cost-effectiveness of the virtual models also remains in question. For one school district in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a contract with Elevate-K12 helped them fill 55 open positions at a cost of about $3.9 million, a savings from the $5 million it would have cost to hire that many in-person teachers. A district representative reported that they were able to save the $1.1 million because they did not have to provide benefits for Elevate K-12 teachers. In contrast, a school district in Charleston County, South Carolina that has used the virtual learning platform, Proximity found that these models were more expensive, as the schools needed to hire paraprofessionals to watch the students during the virtual classes.

Critics point to the fact that there is not yet enough evidence to show that students are achieving positive learning outcomes under these models, but proponents such as Elevate K-12 founder Shaily Baranwal, argue that virtual teaching during Covid-19 took place under emergency circumstances and, with more time to prepare and focus on delivery methods, post-pandemic virtual teaching could be particularly effective. Critics also question whether students’ social experiences and sense of belonging will suffer when they have virtual teachers, and some wonder who will be held accountable for student learning under blended learning models (i.e. the paraprofessionals who are in class every day with the students, or the virtual teachers?). With all these uncertainties, many parents remain skeptical of this virtual solution and question whether virtual teaching will be the best fit for their children.

The bottom line? Freeing up time to teach?

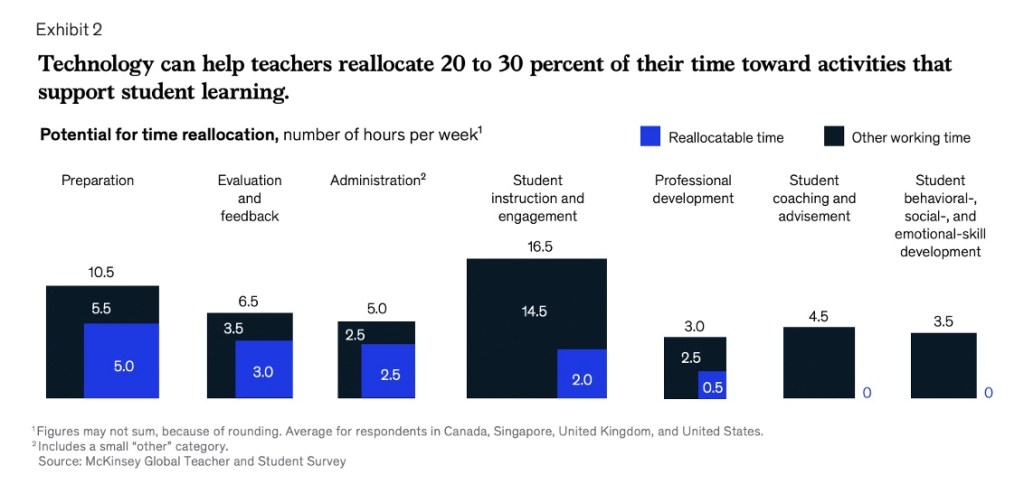

At the end of the day, the success of any of these “innovations” in professional learning depends on whether they can be put in place without adding to teachers already overloaded schedules and extensive set of responsibilities. Post-pandemic articles continue to highlight challenges like a lack of planning time for teachers and excessive time spent in staff meetings as well as hopes that AI may help address these issues by freeing up teachers’ teachers time from administrative tasks and helping teachers create differentiated assignments. Through a survey of 368 school-based employees across the U.S., AI-Equity found that 84% of those who used AI in the Daily/Weekly category reported they were “more excited about continuing education sector work because of AI,” compared to 52% of all respondents, while 94% of Daily/Weekly AI users shared that it made them more productive. According to research from MIT, AI can improve the performance of skilled workers in fields such as consulting by approximately 40%. A report from McKinsey and Co. estimates that teachers could free up 20-30% of their time by using AI and other technologies to support activities such as preparation, conducting evaluations and giving feedback, administrative duties, and professional development. The Christensen Institute argues that teachers may not use their reallocated time for increased student engagement without proper incentives, but freeing up teachers’ time could help to alleviate burnout and increase the attractiveness of the profession.

How artificial intelligence will impact K-12 teachers, McKinsey

However, sources also caution that AI should not be viewed as a panacea for solving these issues, and in fact, may exacerbate some of the challenges that teachers face. As one teacher explained, the expectations developing lessons incorporating AI and other forms of technology “takes extreme planning, and that, we don’t have time for anymore.” Moreover, the increasing use of AI raises numerous questions about the potential impact on students’ learning and development. In particular, as Julia Freeland Fisher cautions, the education market doesn’t prioritize relationship building within its attainment metrics and so may fail to take into account AI’s impact on those relationships. Under those conditions, as Freeland Fisher put it, “the more commonplace that AI companions, coaches, and anthropomorphized bots in learning and support models are, the more fragile students’ social connectedness may become.”