In December’s Lead the Change (LtC) interview Dr. Latrice Marianno argues that meaningful educational improvement must be historically grounded and explicitly centered on equity and justice, not treated as a side effort within school improvement. Despite current challenges, she calls for collective, systems-focused approaches that dismantle structural barriers and urges educators and scholars to continually act as if radical transformation in education is possible. The LtC series is produced by Elizabeth Zumpe and colleagues from the Educational Change Special Interest Group of the American Educational Research Association. A PDF of the fully formatted interview will be available on the LtC website.

Lead the Change (LtC): The 2026 AERA Annual Meeting theme is “Unforgetting Histories and Imagining Futures: Constructing a New Vision for Educational Research.” This theme calls us to consider how to leverage our diverse knowledge and experiences to engage in futuring for education and education research, involving looking back to remember our histories so that we can look forward to imagine better futures. What steps are you taking, or do you plan to take, to heed this call?

Dr. Latrice Marianno (LM): Recently, I had the opportunity to attend the Association for the Study of Higher Education’s (ASHE) annual conference in Denver. During my time there, I visited the Museum for Black Girls and encountered this quote from Angela Davis above one of the exhibits: “You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.” For me, this quote embodies the work before all of us. To heed this year’s call, I am continuing to deepen my work around equitable school improvement in a few ways.

First, I am ensuring that my work is continually grounded in the historical context that has produced and/or maintained the inequities we continually see in education. Critical policy genealogy, which focuses on understanding the origin and evolution of policies (Brewer, 2014; Meadmore et al., 2000), is something I have been drawn toward and intend to engage with more deeply. I find it critically important to understand how policies came to be and the issues those policies were intended to address as that insight can shed light on how educational policies create or maintain inequities. One example that illustrates the importance of understanding the histories of educational policies is the history of state teacher certification policies. While characterized as a policy aimed to enhance the professionalization of teachers (e.g., Hutt et al., 2018), requirements for teachers to pass exams to become certified have long reinforced inequities in access to entering the teaching profession (e.g., Carver-Thomas, 2018). Understanding the history of these policies means an awareness that these certification policies were popularized as a way to justify lower pay for Black educators and later the displacement of Black educators (e.g., Fultz, 2004; Tillman, 2004). Remembering our histories is a necessary foundation if we are to reimagine educational systems.

Second, I will continue focusing on interrogating systems, policies, and practices in educational spaces both in my teaching and scholarship. My work focuses on examining how school improvement systems can be reimagined and redesigned to better support educational leaders to engage in meaningful and justice-centered improvement. For example, Marianno et al. (2024) focuses on state-influenced school improvement plan templates and the extent to which educational leaders are prompted to think about and address inequities. This work opens a conversation regarding how this tool (i.e., school improvement templates) might be redesigned to support educational leaders to center equity in the school improvement planning process. Currently, I teach in a principal preparation program which has allowed me to continually engage with educators and aspiring educational leaders around what this could look like in practice. My teaching allows opportunities for me to learn from and alongside my students as we collectively think about the supports, tools, and professional learning that support educational leaders to think critically about equitable school improvement and act on those commitments in sustainable ways. For example, in my course on data-driven school improvement, we use Bernhardt’s (2017) program and process evaluation tool to prompt them to think about ways school policies and practices create or maintain inequities – an activity they have found useful in prompting them to notice and reflect on inequities within their schools and districts.

Finally, I am committed to supporting and engaging in collective futuring in educational spaces. This commitment means sharing my work in practitioner-friendly formats (e.g., policy reports, and/or practitioner journals like Educational Leadership or Phi Delta Kappan), rather than solely academic journals. This commitment also means continuing to challenge assumptions about what it means to improve a school and supporting educators and educational leaders to think critically about school improvement and educational justice as intertwined endeavors. To envision beyond our current system and imagine what could be. To “act as if it were possible to radically transform the world” and “to do it all the time.”

LiC: What are some key lessons that practitioners and scholars might take from your work to foster better educational systems for all students?

LM: Recently, my work has focused on understanding school improvement planning (SIP) processes and how educational leaders think about and work toward redressing inequities through those processes (Marianno, 2024; additional work forthcoming). Through this research, I found that educational leaders viewed equity as either an implicit part of school improvement planning or absent from that process, and that school leaders were not prompted to think about equity within the SIP process. These views and approaches undermined the district’s expressed equity focus by creating a disconnect between their policy intent and implementation. In my work, I argue for the need to explicitly connect equity with school improvement and begin to identify opportunities to center equity within a process that can often be thought of as parallel to school improvement rather than an integral part of those efforts.

“I argue for the need to explicitly connect equity with school improvement.”

Ultimately, I hope my work inspires folks to be transgressive – to push against the boundaries of what is typically considered improvement within the current educational system (e.g., lack of explicit focus on redressing inequities within improvement efforts). To continually question the assumptions that undergird our collective work in improving education for all students, especially those from historically marginalized backgrounds. To believe in radical transformation and work toward it in our pursuit of educational justice. Toward this end, there are a few key lessons I hope folks can take from my work which collectively emphasizes the importance of being systems-focused, centering the knowledge and experiences of marginalized students and communities, and then leveraging that knowledge to design more just futures.

First, there can be no educational improvement without a focus on redressing inequities. Too often equity is treated or understood like a side project rather than integral to the work of educational improvement (Marianno, 2024). However, as scholars like Gloria Ladson-Billings and Michael Dumas have argued, substantively improving education requires explicitly attending to the racism and antiblackness that shape the current educational system (Dumas, 2016; Ladson-Billings, 2006).

“Too often equity is treated or understood like a side project rather than integral to the work of educational improvement.”

Second, we must focus on reimagining our systems, policies, and practices toward educational justice (Welton et al., 2018). There has been a popular illustration that people, particularly in education, have used to describe equity. This illustration shows three individuals of varying heights standing outside of a fence watching a baseball game. One individual is tall enough to see over the fence without additional support while the other two need additional and varied support. While this illustration has multiple iterations, there is often a comparison between equality and equity in which equality represents everyone getting the same number of boxes to stand on, and equity representing everyone getting what they need to, in fact, see over the fence. The version that most resonates with me includes a visual representation of liberation as the removal of the fence. For me, this representation highlights how education broadly and schools specifically have been designed with particular people in mind (in this case the individual tall enough to see without additional support) and how the removal of the fence would serve everyone. I firmly believe that to ensure marginalized students have equitable and just educational opportunities, experiences, and outcomes, it is critical that our collective work (practitioners and scholars alike) focuses on removing the fences (i.e., barriers) that marginalize students and lead to inequities. Engaging in educational improvement in this way centers the experiences of marginalized students, such that educational spaces are designed with them in mind.

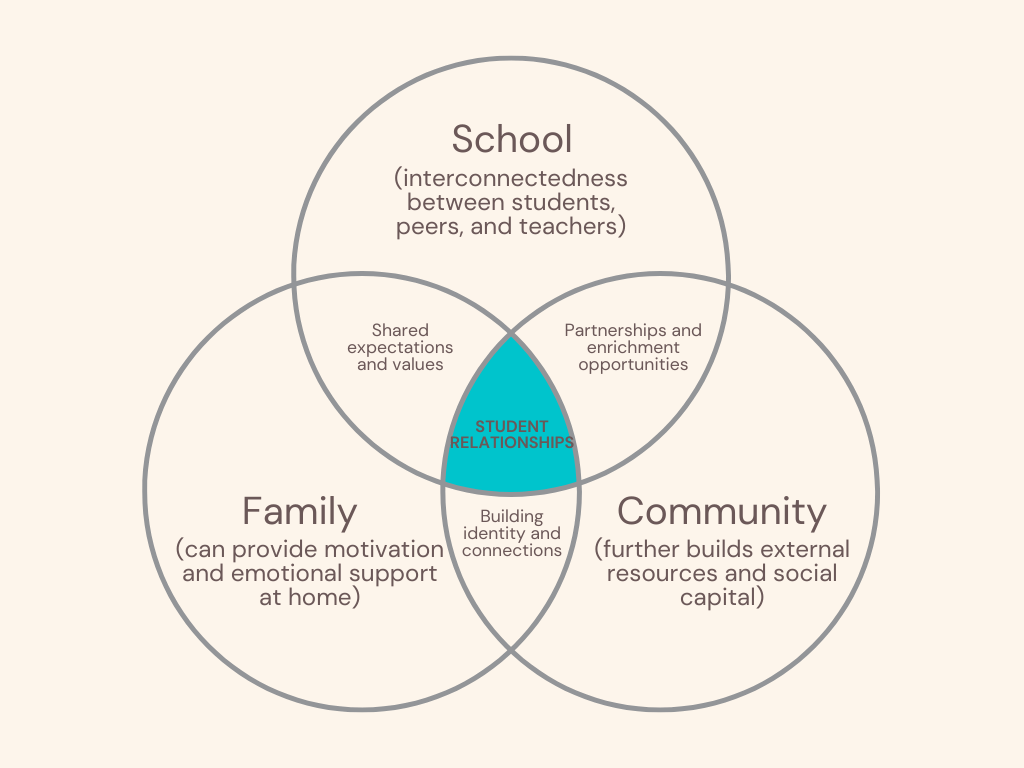

Finally, we must recognize the value of collective knowledge and experiences. Brandi Hinnant-Crawford (2020) notes that we need to “intentionally harvest the collective wisdom of many” to “envision better and plot a course for how to get there” (p. 43). That is, futuring for education requires honoring and valuing the knowledge and expertise of diverse stakeholders – teachers, educational leaders, students, and caregivers. In particular, we need to view students and caregivers as valuable partners who can aid in both addressing the educational problems schools are facing and support imagining an otherwise.

LtC: What do you see the field of Educational Change heading, and where do you find hope for this field for the future?

LM: Honestly, I’m not sure where I see the field of educational change heading. The current climate makes that picture a bit hazy for me. We’re in such a significant period of retrenchment with attacks on academic freedom in higher education, undermining of public education through funding cuts and dismantling the Department of Education, and backlash for anything remotely equitable or inclusive. It is disheartening, though unsurprising. This moment in our history reflects longstanding patterns in American history where movements toward justice are met with resistance and retrenchment. As Decoteau Irby’s (2021) work and the Angela Davis quote shared earlier both remind us, the current moment is a reminder that systems of oppression are constantly at work. We have to act as if we can radically transform the world all the time because systems of oppression are constantly mutating and reinventing. With that in mind, I do have hopes for the field moving forward.

I hope we move toward deeper recognition that equity and justice must be central to educational improvement, not a side project or parallel effort. This is the work. There is no meaningful school improvement work divorced from a focus on educational justice. In my own work, I’ve seen how educational leaders are often unclear about how to integrate equity into improvement work or treat equity as an implied focus undergirding their improvement efforts but in ways that actually undermine those efforts (Marianno, 2024). Specifically, district leaders viewed equity as an implied focus and foundation of all of their school improvement efforts. However, this approach led school leaders in that district to believe that equity was absent from the process altogether and left them unsure of where and how to integrate equity in their improvement efforts because it was not explicitly discussed. Moving forward, I hope we regard equity and justice as non-negotiables that guide how we define problems, reorganize educational systems, and measure the success of educational improvement efforts.

I hope we move toward a more historically grounded approach to school and systems improvement. To meaningfully redress inequities, we must understand how past policies and practices created the systems we currently have. Tracing policy histories, such as the racialized roots of teacher certification requirements or gifted education (e.g., Mansfield, 2016), reveal that many present-day inequities are not accidental, and reinforces the understanding that policies are not neutral. I hope the field continues to deepen its engagement with historical analysis, recognizing that remembering the past is essential for imagining futures that depart from it.

I hope the field continues to shift toward more systemic and collective approaches to educational improvement. When working with aspiring educational leaders in my course on data-driven school improvement and building on the work of scholars like Brandi Hinnant-Crawford (2020), I find they often leave the course with a better understanding of how school systems, policies, and practices shape disparities within their schools and districts and the importance and value of collective approaches to their improvement work. This is my hope for the field – that we engage these ideas not just intellectually but as part of our praxis.

Despite the current moment we’re in, I hope that both scholars and practitioners act as if radically transforming education is possible – and that they do it all the time.