Despite a much more limited budget and a much larger population than “high performing” countries like Finland and Singapore, some common factors help explain Vietnam’s educational success. Drawing on observations from a trip to Vietnam, the second post in this 4-part series from Thomas Hatch focuses on some of the key elements that helped Vietnam make substantial improvements in education. Future posts explore Vietnam’s subsequent efforts to shift to a competency-based approach and some of the critical issues that have to be addressed in the process. For other posts related to Vietnam, see part 1 of this series, Can Vietnam transform the conventional model of schooling? Educational improvement at scale, and earlier posts including Achieving Education for All for 100 Million People: A Conversation about the Evolution of the Vietnamese School System with Phương Minh Lương and Lân Đỗ Đức (Part 1); Looking toward the future and the implementation of a new competency-based curriculum in Vietnam: A Conversation about the Evolution of the Vietnamese School System with Phương Lương Minh and Lân Đỗ Đức (Part 2); The Evolution of an Alternative Educational Approach in Vietnam: The Olympia School Story Part 1 and Part 2; and Engagement, Wellbeing, and Innovation in the Wake of the School Closures in Vietnam: A Conversation with Chi Hieu Nguyen (Part 1 and Part 2).

What does it take to create a “high-performing” education system? For long-standing top-performers like Singapore and Finland a comprehensive educational infrastructure includes:

- Technical capital – adequate funding, facilities, curriculum materials, and assessments

- Human capital – well-prepared, well-supported, and well-respected educators

- Social capital – shared understanding and strong connections and relationships among educators, policymakers, community members and between schools and the education sector and other parts of the society.

In Vietnam, a more limited budget and a much larger population have made it harder to produce and sustain high-quality facilities, a well-prepared and supported workforce, and a tightly connected and coherent education system. Nonetheless, the Vietnamese education system has been able to draw on and develop some key aspects of technical, human, and social capital that have contributed to the establishment of a system that provides almost universal access to education through 9th grade at a relatively high level of effectiveness.

Technical capital: Funding, Facilities, and Textbooks

In terms of funding, the Vietnamese government demonstrated its commitment to education by increasing public spending on education from about 1% of GDP in 1990 to about 3.5% in 2006. Those investments were essential for the construction of large numbers of new primary and lower secondary schools in the 1990s and for the production and distribution of free textbooks for students whose families could not afford them. In turn, these efforts contributed to the substantial increases in enrollment and access to education during that time.

Vietnam has continued that financial commitment to education by spending nearly 20% of its budget (almost 5% of its GDP) on education from 2011 – 2020, a level of spending higher than countries like the US and even Singapore. That commitment was put into a law passed in 2019 that stipulates that the government should spend at least 20% of its budget on education moving forward, though it has not quite reached that level. Notably, the government commitment has included an investment in equity as Vietnam allocates more spending per capita to disadvantaged provinces and municipalities and pays higher salaries to teachers serving in those areas.

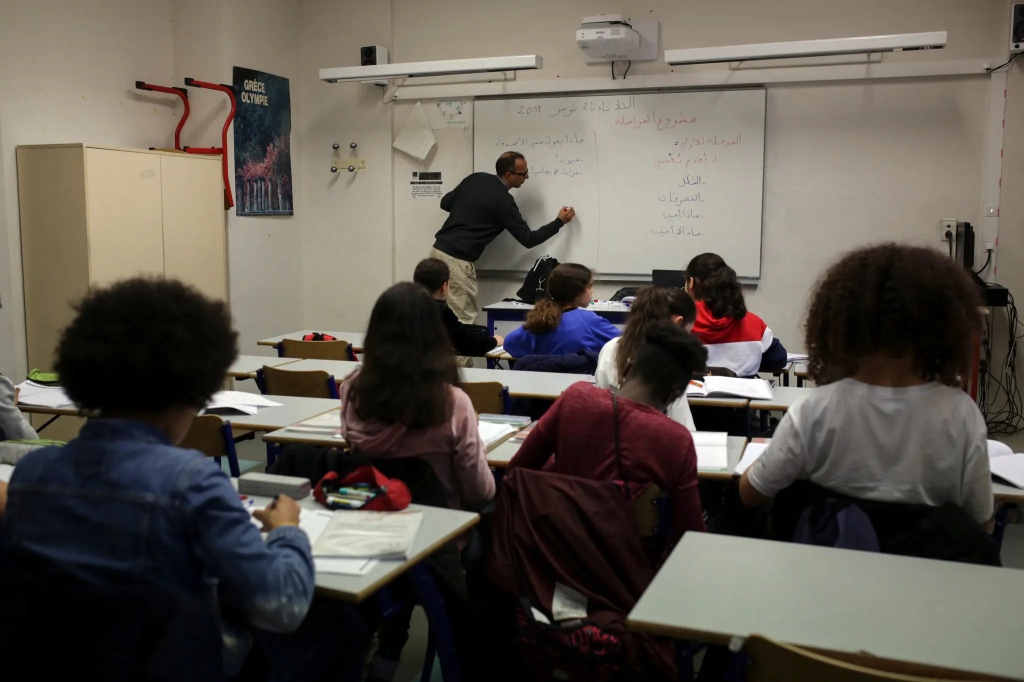

Government-produced textbooks have also played a critical role in the evolution of Vietnam’s education system. These textbooks served as the “de facto” curriculum for some time, with teachers trained to deliver the content in the textbooks and large classes of students moving through the textbooks in a lock-step fashion. Like “managed instruction” approaches that have raised test scores and achievement levels in some districts in the US, textbooks produced by the government with centrally established learning goals may have provided the rapidly increasing student population with access to a common educational experience aligned to conventional assessments and international tests. As a history of the education system in Vietnam explained it, the replacement of textbooks at all school levels in the early 1990s “brought consistency to general education across the nation.”

Human Capital: Respect for teachers and teachers’ expertise

In Vietnam, explanations of the development of the educational system often cite the respect for teachers and their work and dedication as critical factors in the development of the education system. Notably, in OECD’s 2018 TALIS survey of teachers and teaching 92% of Vietnamese teachers report feeling valued by society, some of the highest rates among all OECD countries and astoundingly high compared to the OECD average of 26%. By comparison, slightly over 70% of teachers in Singapore (#2 in the rankings) and slightly less than 60% of teachers in Finland say they feel valued by society. In addition, 93% of teachers in Vietnam reported that teaching was their first choice of career (versus an average of 67% of teachers in other OECD countries). Correspondingly, teacher absenteeism is virtually unknown in Vietnam.

92% of Vietnamese teachers report feeling valued by society…astoundingly high compared to the OECD average of 26%. By comparison, slightly over 70% of teachers in Singapore (#2 in the rankings) and slightly less than 60% of teachers in Finland say they feel valued by society.

There is also some evidence to suggest that, overall, teachers in Vietnam have a relatively high level of expertise. For example, data from the Young Lives project shows that primary school math teachers’ pedagogical skills are the one school variable that explains a significant amount of the difference in the gap between the scores of students in Vietnam and their counterparts in India and Peru. Furthermore, the variance in the effects that teachers have on their students’ learning is much smaller in Vietnam than it is in many other countries, suggesting that there are relatively few really bad teachers.

Social capital: Shared values, common commitment, and relationships

Along with Asian countries like China and Singapore, Vietnam shares Confucian traditions that have placed high value on education for hundreds of years. That commitment to education has also been a critical part of the economic and social development of Vietnam over the last half century of the 20th Century. In 1945, for example, Ho Chi Minh declared Vietnam’s future depended on the education of its children, and that same year, the government issued decrees announcing a call for “anti-illiteracy” campaigns and the establishment of literacy classes for farmers and workers. Shortly thereafter, 75 thousand literacy classes with nearly 96 thousand teachers were serving 2 and a half million people.

The intertwining of education and national development was also evident in the 1980’s as Vietnam’s shift towards a more market-based economy aligned well with the interests of international NGO’s like the World Bank and the Asia Development Bank. These and other international organizations have provided crucial funding and guidance for economic and educational development in Vietnam since the 1990’s.

Those I talked to in Vietnam also emphasized the importance of the commitment to education that parents demonstrate in their support for schools. Vietnam’s education minister in 2015, put it succinctly: “Vietnamese parents can sacrifice everything, sell their houses and land just to give their children an education,”

“Vietnamese parents can sacrifice everything, sell their houses and land just to give their children an education,”

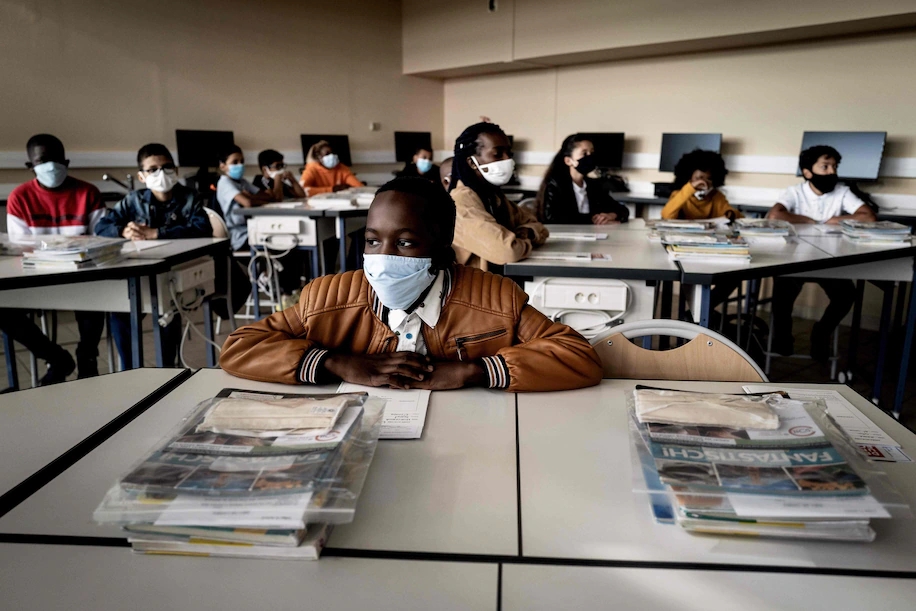

Importantly, students also demonstrate a belief in the power of education and respect for their teachers. 94% of the Vietnamese students surveyed as part of the PISA tests in 2015 agreed with the statement that “It is worth making an effort in math, because it will help us to perform well in our desired profession later on in life,” and surveys from the latest PISA test in 2022 showed that the proportion of class time teachers in Vietnam have to spend keeping order in the primary classroom (9%) is one of the smallest among all participating countries.

Along with these shared values and commitments, Vietnam also appears to have developed some strong relationships between educators, government officials, and community leaders and parents. Attention to these relationships may have played a particularly valuable role in the effort to extend and support schooling in rural ethnic minority areas. Phương Minh Lương, who has worked and conducted research with several ethnic minority communities, explained it to me this way: “That is the power of the collective or what we might call the ‘power with.’ There’s close coordination between authorities at grassroots levels and schools, with monthly meetings between the village or what we call the commune authorities and school leadership and educators. These include school officials like the headmaster and representatives of mass organizations like the Women’s Union, Youth Union, and Study Promotion Associations at the village level. These meetings are organized by the commune authorities, and they discuss all the problems related to the life of the local people in the village and in the school. Then if there is a problem, like there are children who have dropped out, then the authorities can support the school in that area and they can come to see what are the reasons these children dropped out, and are there any solutions to get these children back to school.”

“That is the power of the collective. There’s close coordination between authorities and schools, with monthly meetings between the village or what we call the commune authorities and school leadership and educators.”

Reflecting on the extent and impact of this coordination, Lương described instances in which educators or village heads travel significant distances to meet parents and students in their homes, and, when necessary, provide transportation to help the students get back to school. Illustrating the shared cross-sector commitment, another interviewee reported that in some mountainous regions, parents who live far from the local schools can send their children to temporarily live at border army posts where soldiers then transport the students safely to the local school.

Later this month: Challenges and opportunities for learning and development in Vietnam: Can Vietnam transform the conventional model of schooling (Part 3)?