In Part 2 of this interview Barbara Gross talks with Thomas Hatch about the effects of the school closures on Italian schools and discusses some her comparative studies with colleagues in Austria, England, and Germany during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Part 1 focuses on Gross’ research and observations of the immediate response to the school closures in Bozen-Bolzano, a multi-lingual region in Northern Italy. Gross is currently Junior Professor in Educational Science with a Focus on Intercultural Education at the Faculty of Philosophy at the Chemnitz University of Technology in Germany. Until October of 2022, she was an Assistant Professor at the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano, in Northern Italy. Some of Gross’ work explores this linguistic diversity as Italian is the language of instruction in Italian language schools and taught as a second language in German-language schools; German is the language of instruction in German-language schools and taught as a second language in Italian-language schools (Further Language Learning in Linguistic and Cultural Diverse Contexts: A Mixed Methods Research in a European Border Region). Because of the right to schooling in these official languages teacher education also has to prepare future teachers to work in the respective systems(Approaches to Diversity: Tracing Multilingualism in Teacher Education in South Tyrol, Italy).

This interview is one in a series exploring what has and has not changed in education since COVID. Previous interviews and posts have looked at developments in Poland, Finland, New Zealand, South Africa, and Vietnam.

Thomas Hatch: What about now? Have their been changes in terms of the uses of technology and “digitization”? Is that something that’s still going on or that is a focus for professional development during the summer?

Barbara Gross: The focus on digitalization was also there in the beginning of the pandemic and that’s an emphasis that’s continuing. But there was very different handling of this depending on the capacity of the school and the capacity of the teachers. The teachers often had to have their own devices, and they had to have digital competencies. The response depended on the individual effort of teachers, not just what the government expected teachers to do.

TH: Were there other issues that the government tried to address?

BG: They thought about trying to be innovative with buildings and facilities. In fact, they bought a lot of chairs during this period. The aim was to provide chairs with wheels, but soon it emerged that to ensure for social distancing that wasn’t really helpful. There were also some governmental decisions about how to use funding which weren’t always supported by the community or by teachers.

TH: What about other repercussions from the pandemic? Are there particular concerns around education that have emerged or is it more like the pandemic is over and we’re moving on?

BG: What is still discussed are teachers’ and students’ digital competencies. In addition, there have been some concerns about student learning and also about drop-out rates. There were higher dropouts because students didn’t see the necessity any more of going back to school. This is especially a problem for students from families who are already marginalized. There are also reports stating that students from families with the lowest levels of economic resources decided not to go to a secondary school or to a university, but instead to do more vocational training. So there has been some “catch-up” discussion, particularly about having longer school hours or schooling on Saturdays, or adding school time in June. But there were also many voices that were opposed to this, and one of the things we’ve written about is that learning isn’t so linear, so just adding more school hours doesn’t necessarily mean you are adding more learning. We know that learning is much more complex. We can’t just say “you lost 10 hours, so now we’ll give you 10 more back.”

…learning isn’t so linear, so just adding more school hours doesn’t necessarily mean you are adding more learning. We know that learning is much more complex. We can’t just say “you lost 10 hours, so now we’ll give you 10 more back.”

There was also some data that children from vulnerable families were not getting enough healthy food or getting as many support services during the COVID lockdown as they were before. Many of those children before COVID went to school and afterschool all day and got a proper meal at lunch; but during COVID, when the schools were closed, they didn’t have those services either and that affected their health. There have also been a lot of reports about the wellbeing of all students and how they missed out on all the social aspects of schools. The consequences are likely to continue to affect their lives.

TH: Can you tell me a little bit about the comparative research you’ve done about how different education systems are talking about and responding to the COVID crisis in education?

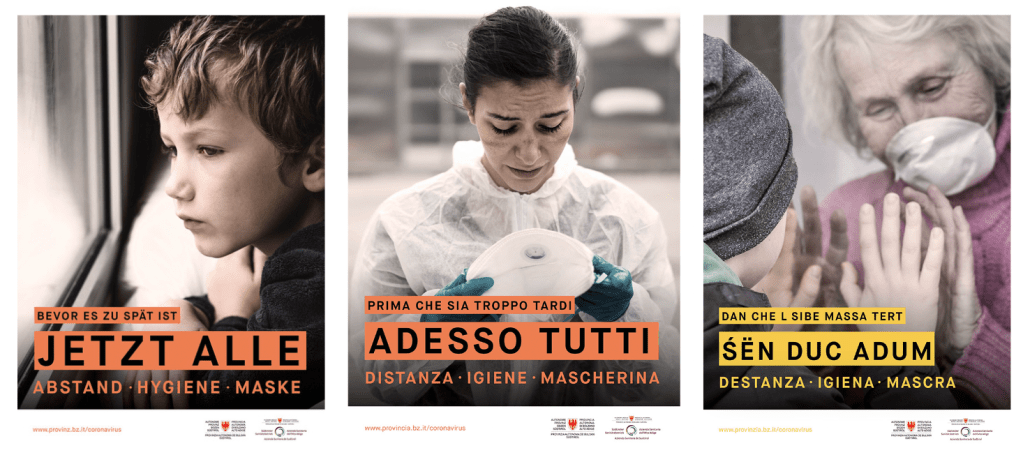

BG: In our comparative research we looked at educational policy responses to the pandemic in countries like Italy, Austria, Germany and England. We’ve seen it’s all about trust and what research governments trust. The priorities have been on health, security, and on the economy so policymakers have been listening to the medical experts and economists. Educational research has not been referred to and included very much. For example, in Italy we’ve seen that a lot of women have lost their jobs because of the pandemic, so now there’s more interest in having more early childhood services and more interest in creating special programs for enhancing specific competencies for women.

We’ve also seen that differences among countries depending on how states define who is “vulnerable” or “in need.” For example, we have seen that the focus in Italy has been on inclusive schooling. From the 70’s on, Italy has had schools for all, including children with disabilities or learning difficulties. During COVID, in the discussions of which students needed support, there was a focus on making sure that students with disabilities and learning difficulties got extra support, but it was mostly left up to the teachers to figure out how to give them more attention or other kinds of support. In Italy, there was not as much focus on other aspects of diversity, for example, on children whose home language is different from the language of instruction, and, compared to other countries, less focus in Italy on socioeconomically disadvantaged learners.

We’ve also seen that differences among countries depending on how states define who is “vulnerable” or “in need.”…In Italy, there was not as much focus on other aspects of diversity, for example, on children whose home language is different from the language of instruction.

TH: And how did the Italian response compare to what you saw in other countries?

BG: In Italy, the reopening of schools was more delayed, as there wasn’t as much of a focus on reopening as there was in England, Germany and Austria. In Germany and Austria, for example, there were re-openings at least for some students in May of 2020. There were also differences in terms of who was considered “vulnerable.” In Germany, there was more of a focus on immigrant students and less on students with special educational needs. In Austria, in the government documents we see the focus on linguistic diversity and the children who did not speak German. They argued that if these students didn’t go to school, then they would not learn to speak German, and the consequences would be severe.

There were also differences in terms of digitization. Both England and Austria were well-prepared before the COVID outbreak, but Germany was not. In Germany digitization overall is still an issue, and there were discussions about it during the pandemic. In Italy, they were aware of the digital gap so the focus during COVID was on filling this gap. In terms of “catch-up,” we’ve also seen that equality was prioritized of equity. After the first wave, in Germany, England and Italy there was a discussion about who was most in need, but then when it came to actually giving support, no differentiation in the provision of support measures was made. Of course, this is also a source of inequality – equity does not come with equality.

After the first wave, in Germany, England and Italy there was a discussion about who was most in need, but then when it came to actually giving support, no differentiation in the provision of support measures was made. Of course, this is also a source of inequality – equity does not come with equality.

We also found in our work in Italy and Austria that schools have also learned from COVID that they have to emphasize wellbeing, particularly the social aspects of wellbeing and students’ relationships with their peers. If those relationships are missing, if students can’t go to school, they don’t have the same opportunities to develop their social competencies. We found that how the schools and teachers in different countries have responded to that depends on how “output oriented” they are – how much they focus on producing particular outcomes. For example, we’ve seen a stronger output-orientation in England than Italy. But in all the countries, one of the main messages of the pandemic in education has been that already existing difficulties exacerbated.