In November’s Lead the Change (LtC) interview Edwin Nii Bonney emphasizes that educational research and practice must “look back” by acknowledging colonial legacies and marginalized histories while “looking forward” by centering Indigenous, vulnerable, and community voices. His work highlights deep listening, intergenerational collaboration, and community-designed solutions as essential to dismantling deficit narratives and creating equitable educational systems. The LtC series is produced by Elizabeth Zumpe and colleagues from the Educational Change Special Interest Group of the American Educational Research Association. A PDF of the fully formatted interview will be available on the LtC website.

Lead the Change (LtC): The 2026 AERA Annual Meeting theme is “Unforgetting Histories and Imagining Futures: Constructing a New Vision for Educational Research.” This theme calls us to consider how to leverage our diverse knowledge and experiences to engage in futuring for education and education research, involving looking back to remember our histories so that we can look forward to imagine better futures. What steps are you taking, or do you plan to take, to heed this call?

Edwin Nii Bonney (ENB): As someone who grew up in Ghana and went through K–12 and college there, I have come to appreciate the wisdom of my elders. That wisdom, often carried in proverbs and the principle of Sankofa, reminds us to look back and learn from the past so that we do not repeat its mistakes. In my scholarship, I wrestle with the reality that educational systems remain deeply embedded in coloniality. We are still grappling with the legacies of colonialism especially in the global South, and those legacies have not disappeared (Bonney, 2022). They persist in the languages we speak and use to instruct students, the books we read, our perceptions of ourselves, our standards of beauty, and even our justice systems (Bonney, 2023; Bonney et al., 2025a). Colonialism continues to shape much of who we are and how our societies function. It is essential that we acknowledge that the legacies of colonialism are still with us. It was not that long ago, and its effects continue to reverberate in our educational systems and beyond.

Having lived and schooled in four different countries, I have come to realize that in every society there are marginalized and vulnerable groups. The dominant discourses in any context, whether social, cultural, or educational, are often so pervasive that marginalized voices, ideas, and ways of knowing are easily erased or silenced. Indigenous wisdom, local knowledge, and community customs are frequently pushed aside. This understanding shapes how I approach my scholarship. We must continually examine how educational leadership, policies, and practices have historically and presently marginalize the ways of being, speaking, and doing of those who are not part of dominant groups. Whether in the United States, Ghana, or elsewhere, there are always minoritized voices whose perspectives are excluded from how education is designed and enacted. Because of that, I believe it is vital to ask how we center the ways of speaking, knowing, and being of Indigenous, marginalized, and vulnerable communities in education. How do we ensure that their experiences and insights shape what we study, how we study it, and how we interpret what we learn?

“We must continually examine how educational leadership, policies, and practices have historically and presently marginalize the ways of being, speaking, and doing of those who are not part of dominant groups.”

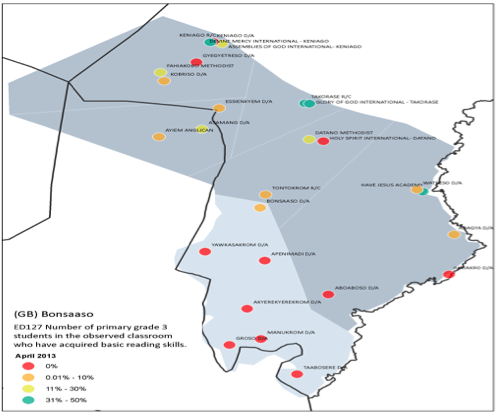

In my own scholarship and service, I see my role as coming alongside communities and families, not as an expert above them but as a partner who recognizes them as experts of their own experiences. They understand the root causes of the challenges they face and often hold the wisdom to identify meaningful solutions. In Bonney et al. (2025a) in listening to students who had not been able to obtain passing grades in Math, many of them, after retaking the exam multiple times, I learned that they struggled to understand and make sense math concepts taught in English. They felt like failures until they went against the norm as experts of their own experiences to learn in their native languages. Learning in their own native language according to these students brought them success on the first try even though the system told them it was impossible. As we think about the future of education and research, we must keep asking: whose voices are missing from the table? Whose perspectives are absent from the design process? Which families are not engaged in our schools, and how do we empower them to participate fully? We must always ask who we are not serving well and how we can do better. When we look back at history, we see that we have not always served everyone equitably. Therefore, it must remain at the forefront of our work in education to ask, whose voices are we still not hearing?

“I see my role as coming alongside communities and families, not as an expert but as a partner who recognizes them as experts of their own experiences.”

LtC: What are some key lessons that practitioners and scholars might take from your work to foster better educational systems for all students?

ENB: Much of the work I do alongside educational leaders, students, and families begin with listening. It starts with listening deeply to the experiences of different groups and how they encounter systems of oppression. This kind of listening is to not to defend or to critique but to learn from their perspectives, their realities, and their ways of knowing and being. The next principle is building relationships across generations and forming coalitions among groups who are affected by similar problems of practice or systems of oppression. When these coalitions come together around community-informed problems and community-designed solutions, we are better able to address the issues that matter most to them. In Bonney et al. (2025b), I share about a community-based organization that brings together everyone in their village from as young as seven years to as old as 80 years. The organization gathers the elders to recount stories about the history of their community in their native language. The young people record and document the oral history and then create plays in their native language, where they dramatize the stories on digital media and on stage to be a resource for local schools because there were no resources to teach their native language other than English. This community led movement was in decreasing use of their native language. Communities understand their own challenges, and when they help design the solutions, those solutions are more authentic, effective, and sustainable (Costanza-Chock, 2020). Through these relationships and through genuine listening, we can begin to challenge deficit discourses and narratives that blame individuals instead of systems for the inequities we see in education. Deficit thinking overlooks structural causes and often misplaces responsibility. But lasting change requires us to shift our attention to the systems, policies, and practices that create and sustain inequity.

Change in education will come only through broad coalitions that include not only researchers and educational leaders but also students, teachers, families, community members, elders and even naysayers. Their knowledge, lived experiences, and cultural wisdom are essential for reimagining a more just and equitable educational future. As we engage in this work, it is important to keep asking which solutions are working, for whom, and under what conditions (Hinnant-Crawford, 2025). Sometimes a solution may appear successful in one area but create unintended problems in another. When that happens, we must be ready to respond quickly to stop any harm. Change is not static; it is a continuous and reflective process. At the heart of this work is a simple but powerful truth: we must be intentional about involving those most affected by the problems we aim to address. We must center community expertise, engage families and students as co-creators of change, and together expose even small variations in outcomes for students as opportunities to learn. Finally, we must continue to seek out and listen to the voices and stories of those still impacted by systems of oppression or persistent inequities. Because meaningful change in education begins with listening, building relationships and broad coalitions that endure when we work together to challenge inequitable systems and co-create a more just future. These are the foundational blocks to a justice-oriented improvement approach to undo oppressive systems in education.

“[M]eaningful change in education begins with listening, building relationships and broad coalitions that endure when we work together to challenge inequitable systems and co-create a more just future”

LtC: What do you see the field of Educational Change heading, and where do you find hope for this field for the future?

ENB: The nature of change is that it always comes with uncertainty. Sometimes that uncertainty can bring frustration on one hand or excitement on the other. We can never fully know what the future holds or what the field might look like. We cannot predict what new policies, reforms, or interventions will emerge, or what discourses will shape the field. What I do know is that we can always look back to learn. We can recognize that, as a society and as a field, there are things we’ve done well and others we have not. One of our core goals must be to serve all children well. That means preparing researchers, educational practitioners, students, and teachers so that we can meet the diverse needs of all types of learners. It also means continuing to prepare teachers for a field that is increasingly complex with diverse students who have diverse needs. It also means preparing educational leaders to create inclusive and collaborative environments that enable teachers and staff to do their best work to serve students equitably.

So, although there is uncertainty about the future, one thing we can hold on to is that we know what we value and how to prepare for that future, whatever it looks like. More than what gives me hope is what energizes me. In Bonney et al., (2024) we created an edited volume, to center and hear from educational practitioners on the front lines and how they work with students, teachers, parents, and community to tackle problems of practice in their local schools and districts. In times of uncertainty, the best people to hear from are those on the front lines. Working alongside with these scholars, educational leaders, and practitioners, in the trenches trying to figure out how to serve all students well makes me expectant that things will change continuously for the better. They’re asking critical questions: How do we better support our teachers? How do we solve problems of practice? How do we address discipline issues or chronic absenteeism? How do we engage families more effectively? How do we reduce the overrepresentation of Black and Brown students in special education? How do we increase their representation in gifted and Advanced Placement courses? These are the kinds of questions that inspire hope for the future. Even though the future may be uncertain, we can still prepare for said future. Personally, I am not as concerned about where the field of educational change is heading but rather about preparing my students and practitioners for today’s challenges. I believe that the same justice-oriented and community-centered approach to solving today’s problems will help us address the problems of tomorrow.