What are the critical education issues facing India following the school closures of the pandemic? What are some of the practices and initiatives that could serve as building blocks for improving one of the largest educational systems in the world? Haakon Huynh explores these questions in the second part of a two-part series on K-12 education improvement efforts in India. The first part looked at some of the long-standing barriers hindering the development of India’s educational system. For previous posts related to education in India see: From a “wide portfolio” to systemic support for foundational learning: The evolution of the Central Square Foundation’s work on education in India (Part 1 and Part 2); and Sameer Sampat on the context of leadership & the evolution of the India School Leadership Institute.

Beyond the largely school-based, academic concerns of foundational learning and increasing access to colleges and careers, four other interwoven issues – including chronic absence, mental health, nutrition and sustainability – have been receiving increasing attention in the aftermath of COVID-19 related pandemic in India. The discussion of these issues illustrate both the critical challenges as well as the kinds of initiatives and innovations that are already being pursued that can give hope for the future in India and beyond.

Chronic absenteeism: When enrollment isn’t enough

For some time, the Indian government has focused on increasing enrollment, but in recent years, chronic absenteeism may have taken over as a critical issue. In fact, the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2024 shows that enrollment now exceeds 98% among 6–14-year-olds. Encouragingly, early childhood enrollment has also risen significantly, and digital access among adolescents has become nearly universal. At the same time, data from ASER 2021 showed that over 20% of rural primary school children were not attending school at all even after reopening, and school-level data reported that 21% of schools had fewer than half their students attending regularly, though the extent of absences varied extensively by region. In some states, absence rates were slightly more than 10%, but in places like Bihar, West Bengal and Madhya Pradesh they ranged from 40% to 50%. In rural Telangana 75% of students missed 10 % or more of all school days and more than 50% missed 15% or more.

As in the United States and other countries, poor attendance and chronic absenteeism in India are connected to negative learning outcomes and increased chances of dropping out, particularly for already disadvantaged populations (National Collaborative on Education and Health, 2015; Uppal et al., 2010). Although research in India has been limited, common factors contributing to absences include disinterest in school, illness, weather, transportation, work demands, family obligations, (Malik, 2013) poor peer relations and being overage (Shah, 2021). Girls also have a lower attendance rate than boys, reflecting cultural and gender-related issues such as menstruation, child marriage, household responsibilities, and societal expectations (Raj et al., 2019). Although programs like mid-day meal offerings can increase attendance for part of the day, students may still leave after lunch, so that even students who are counted in a morning roll-call may still miss a substantial part of the school day. Complicating matters, most schools in India still rely on a manual system for tracking attendance which makes it difficult to collect, review, and act on the data in a timely way at the school level, and a lack of digitization means it’s difficult to aggregate and analyze the data across schools. All of which means reporting of attendance is subject to fraud and manipulation.

Responding to some of these specific issues, one pilot effort in ten schools – the Chronic Absenteeism Assessment Project (CAAP) – in the state of Telangana developed a way to measure student attendance using a fingerprint scanner connected to a tablet which allowed data to be analyzed relatively quickly. Beyond the technology, this approach included the development of “Education Extension Workers” (EEWs) who could follow-up with absent students and their families, investigate the reasons for absences, and respond appropriately.

Mental health: Entering the mainstream?

Although attendance and chronic absence began receiving attention before the pandemic, mental health has been a neglected and often taboo topic. None of India’s 22 languages have words for “mental health,” “depression,” or many other mental illnesses, yet a national survey in 2016 documented 50 derogatory terms used for people suffering mental illnesses. At the same time, even before the pandemic, India had one of the highest suicide rates in Asia. Furthermore, according to the same national survey, over 80% of those who did report mental health problem could not access adequate treatment – not surprising given that India only had three psychiatrists for every million people and even fewer psychologists (in contrast, the US has almost 400 psychiatrists and psychologists for every million people).

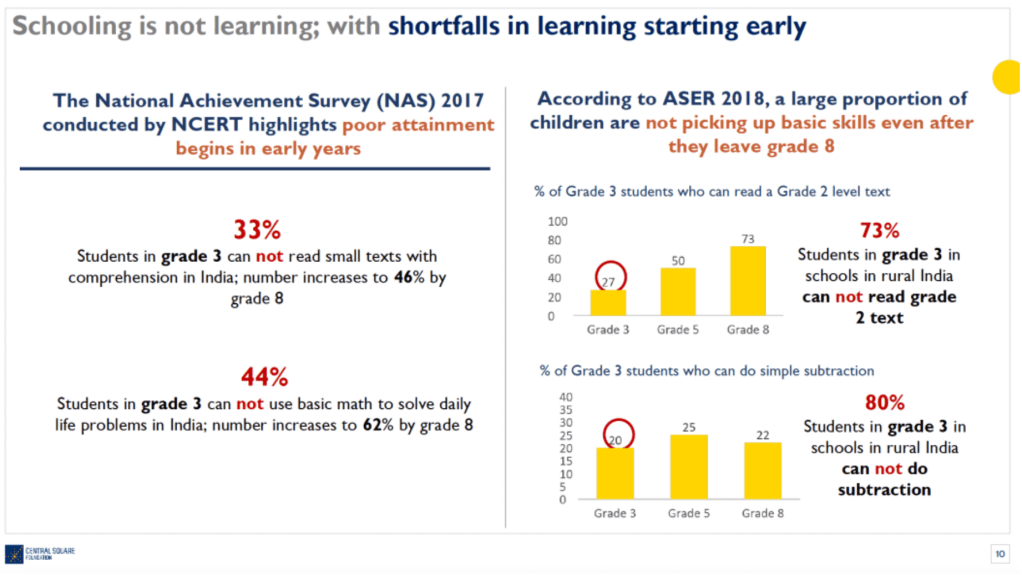

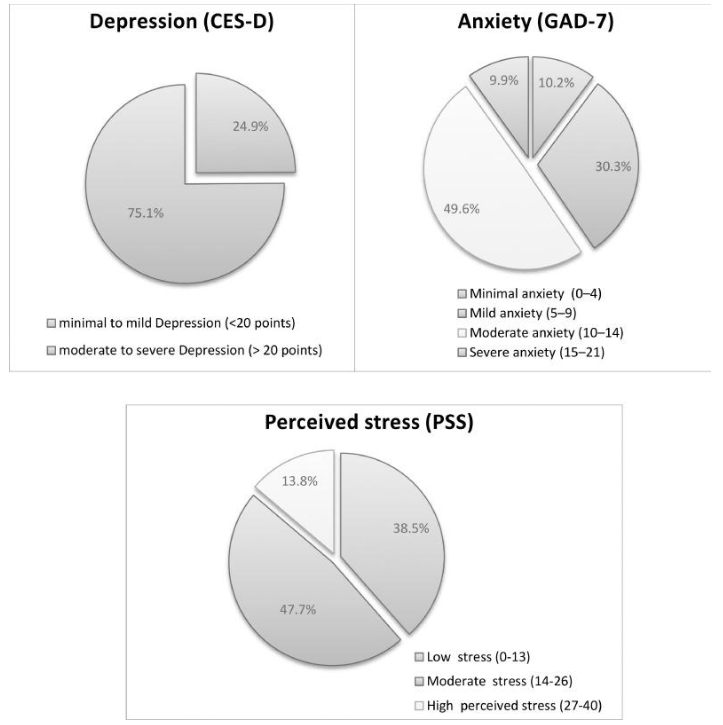

The pandemic and associated lockdowns only made the situation worse. Even by the middle of 2020, surveys were suggesting that as many as 40% of participants reported suffering mental health problems and more than 65% of mental health professionals surveyed reported in increase in self-harm behaviors among their patients. By 2021, the mental health of Indian university students had worsened significantly, with over 75% experiencing moderate to severe depression and nearly 60% experiencing moderate to severe anxiety. School counselors have also noted rising mental health concerns, with one study reporting that counselors are dealing with challenges ranging from heightened anxiety and social isolation to increased aggression and cyberbullying.

These increases, however, also may reflect a growing willingness to recognize, report and seek treatment for mental health issues. Furthermore, as early as 2020, the Indian government launched the Manodarpan initiative to provide psychosocial support for students, families, and educators. Among other things, the initiative provides counseling resources, a national helpline, and school-based mental health programs.

Attention to socio-emotional learning is also growing in some schools in India as approaches like “feelings check-ins” are supported by programs like the Simple Education Foundation and Apni Shala. This practice invites students to begin the school day by identifying and sharing how they feel, often using a simple visual chart or prompt. Other initiatives include POD Adventures, a smartphone-based mental health intervention co-developed with Indian adolescents. Among other components, the app prompts youth to identify their feelings, name the source of their stress, and plan responses.

Nutrition: India’s triple burden

Nutrition is another concern receiving more attention post pandemic. India faces a so-called “triple burden” of undernutrition, micronutrient deficiency, and obesity. About 6% of children are overweight or obese and over 65% are anemic.

Although some progress had been made on these health issues, the pandemic set that work back. Disruptions to India’s food systems included interruptions of food programs, reduced access to healthy foods, and increased costs. Illustrating the challenges, the COVID-19 lockdown in the state of Karnataka led to the suspension of the Mid-Day Meal (MDM), iron–folic acid (IFA) supplements, and deworming programs. In turns, those disruptions likely contributed to increases in the rates of children who were underweight from about 30% in 2017 to 45% in 2021 while anemia rates nearly doubled from 21% to 40% during the pandemic.

These disruptions, however, along with government and civil society awareness campaigns may also have brought greater attention to these issues in recent years. Even before the pandemic, the Ministry of Education sought to support children’s nutrition and healthy eating by implementing School Nutrition (Kitchen) Gardens. That national program, launched in 2019, recommends that every class spend one to two hours per week in the school’s garden and encourage the integration of garden activities into the school curriculum. The produce from these gardens is intended to supplement school meals, supporting both nutrition and experiential learning.

Although India has issued national guidelines mandating school nutrition gardens in all schools, progress has been uneven. Some states have taken it further by encouraging families to develop their own gardens. The Nutrition Garden program, implemented in rural areas of the states of Tamil Nadu and Odisha, trained families to cultivate diverse vegetables and offered structured nutrition education. In a similar program in rural schools in in the state of Andhra Pradesh, a 2025 study found that after receiving gardening kits and nutrition education through their government schools, students established kitchen gardens at home and increased their vegetable consumption by 90%.

Sustainability: Preparing for a warmer planet

Climate change has also emerged as both a critical challenge but also a potential driver of innovation in education in India. In 2019, India was ranked number seven among a list of the countries affected by the changing environment, but 65% of the Indian population had not heard of climate change. As one step in raising awareness about the issue, India’s 2020 National Education Policy (NEP), emphasized the need for environmental education in schools and suggested a shift from content-based learning to skill-based learning in climate education. At the same time, some Indian universities have emerged as global leaders in sustainability with India being the best-represented nation in the 2024 Times Higher Education Impact Rankings assessing universities’ contributions to each of the 17 United Nations sustainable development goals (SDGs). Institutions such as Saveetha Institute, Shoolini University, and JSS Academy are ranked among the world’s top performers, contributing to clean energy (SDG7), health (SDG3), and sanitation (SDG6).

Although the costs can be prohibitive, architects in India have also been exploring sustainable schools designed explicitly to respond to and take advantage of the environmental conditions in their local contexts. One of those schools serves a desert township in Ras that houses families of those working in a cement plant. To minimize the impact of the harsh sun and make the structure as energy-efficient as possible, the architects created a fragmented layout of sheltered and semi-enclosed spaces to maximize shade and ventilation. A Central Board of Secondary Education school run by the Rane Foundation in a rural village of Tamil Nadu relied on local and recycled materials to create a design that eliminates the need for air-conditioning. Another private, international school in Bengaluru sought to take advantage of its setting near a national park to cultivate respect and curiosity in the natural environment. To do so, the design creates both inside and outside learning spaces and allows students to get perspectives on the trees and plantings from multiple perspectives.

The green economy’s rapid expansion and the promise of high-paying jobs in fields like renewable energy and environmental policy have also contributed to a surge in the numbers of students interested in sustainability education. Supporting those interests, several initiatives seek to engage students in learning about and promoting sustainable practices. For example, the Green School Initiative involves over 35,000 students, more than a 1000 teachers across 110 schools in supporting student-led efforts to promote sustainability in their local communities. In addition to providing environmentally-based curricula, the Initiative sponsors action projects and capacity-building activities related to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, particularly in areas of Energy, Water, Forests & Biodiversity, and Waste.

The Green Schools Programme and other efforts support student engagement in issues of sustainability by giving them the opportunity to both study and grade their schools on their environmental performance. For example, Birla Vidya Niketan a school of 4,000 students in New Delhi has become known for its attention to sustainability and its student-led electricity audits. By appointing student monitors to ensure fans and lights are switched off when classrooms are empty, the school promotes peer-led accountability in daily energy use. The chosen students complete simple forms to track behavior and encourage energy-saving habits among classmates. To assess impact, the school analyzes changes in its electricity bills. Principal Minakshi Kushwaha emphasized the role of peer education, noting that students are more receptive to feedback from fellow students than from teachers alone. Another public school in Delhi, RK Puram, involves students in energy audits and also involves them in projects related to renewable energy and waste management that build on the school’s commitment to developing sustainable facilities. Demonstrating the international power of these efforts, student audits and related projects can also be found in the PowerSave Schools Program in Southern California in the Let’s Go Zero campaign in the UK.

Common denominators and synergies?

The challenges of mental health, chronic absence, nutrition, and sustainability are deeply rooted and disproportionately impact the most marginalized; but these are not isolated challenges. The challenges interconnect and build on each other creating a set of barriers that can undermine learning and development. Although the complexity and scale of the education system in India compounds the challenges, coordinated efforts to address these critical challenges could also provide cascading benefits in the largest education system in the world.