What’s involved in strengthening relationships among students? This week, Hannah Nguyen surveys some of the news and research that discuss the possibilities for creating a whole ecosystem of relationships to support students in schools. This post is one in a series exploring strategies and micro-innovations that educators are pursuing following the school closures of the pandemic. For more on the series, see “What can change in schools after the pandemic?” For examples of micro-innovations in tutoring and access to college see: Tutoring takes off; Predictable challenges and possibilities for effective tutoring at scale; Still Worth It? Scanning the Post-COVID Challenges and Possibilities for Access to Colleges and Careers in the US (Part 1, Part 2).

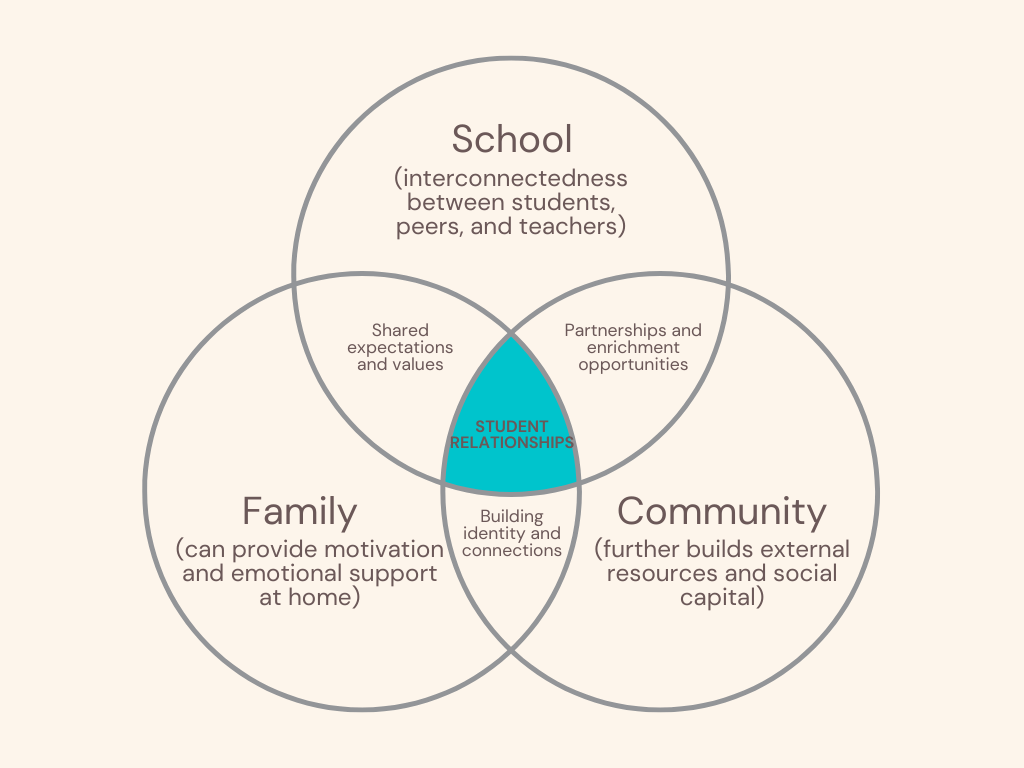

Strengthening student relationships can begin in schools, but ultimately it involves building a whole ecosystem of relationships that supports students and their connections with their peers, their teachers, and the members of their families and the wider communities. Healthy relationships support students’ academic achievement, engagement in school, and social-emotional development. In particular, students’ friendships can provide emotional support that contributes to their learning, and strong connections to the members of their school community have a positive correlation to students’ level of engagement and motivation which also supports higher academic performance. In addition, students’ relationships play a crucial role in their sense of belonging – the extent to which students feel personally accepted, respected, included, and supported by others in the school environment. In turn, students with a strong sense of school belonging are more likely to report high levels of academic motivation, less likely to experience emotional distress, and less likely to be absent or drop out. A sense of school belonging has also been shown to reduce behavioral issues and promote mental health, while its absence is linked to loneliness, depression, and risk of suicide.

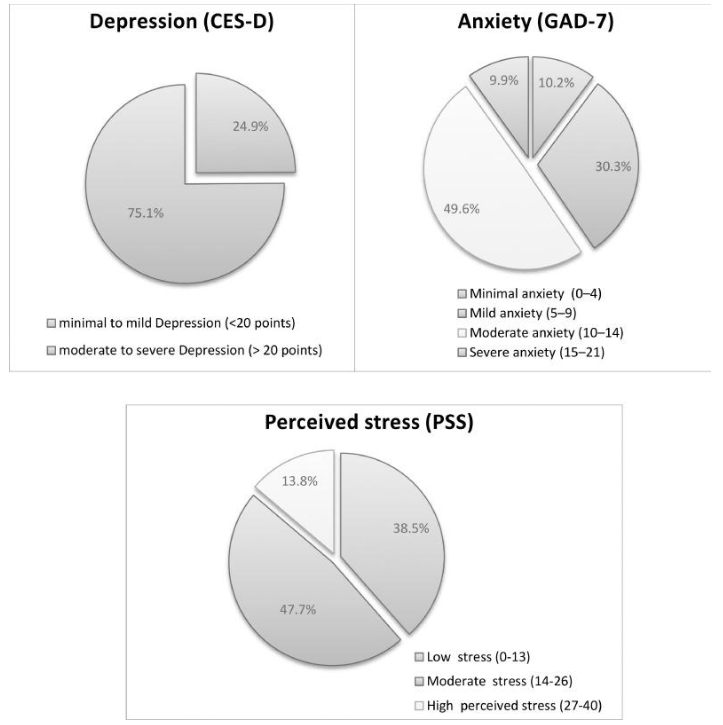

Despite the well-documented benefits of strong interpersonal connections in educational settings, many students today lack access to these supportive relationships. The COVID-19 pandemic compounded the challenges for developing positive relationships as the school closures and quarantines contributed to social isolation and increased loneliness, stress, and anxiety among students as well as adults. Showing just how widespread the impact has been, these disruptions to relationships extended far beyond school settings contributing to a 40% increase in babies lacking strong emotional bonds with their mothers just after the onset of the pandemic.

Even with some awareness of the negative impact of the pandemic on students’ relationships, educators may underestimate the extent of the problem. Julia Freeland Fisher and Mahnaz Charania, who have written extensively about the power of peer relationships, note that over 85% of adults in K–12 schools report that they are building strong relationships with students, but only 45% of students reported experiencing such strong developmental relationships with their teachers. In addition, less than 40% of 10th graders say “‘most of the time they feel they belong at school’” while more than 60% of parents with 10th graders think they do.”

“Less than 40% of 10th graders say ‘most of the time they feel they belong at school’ while more than 60% of parents with 10th graders think they do.”

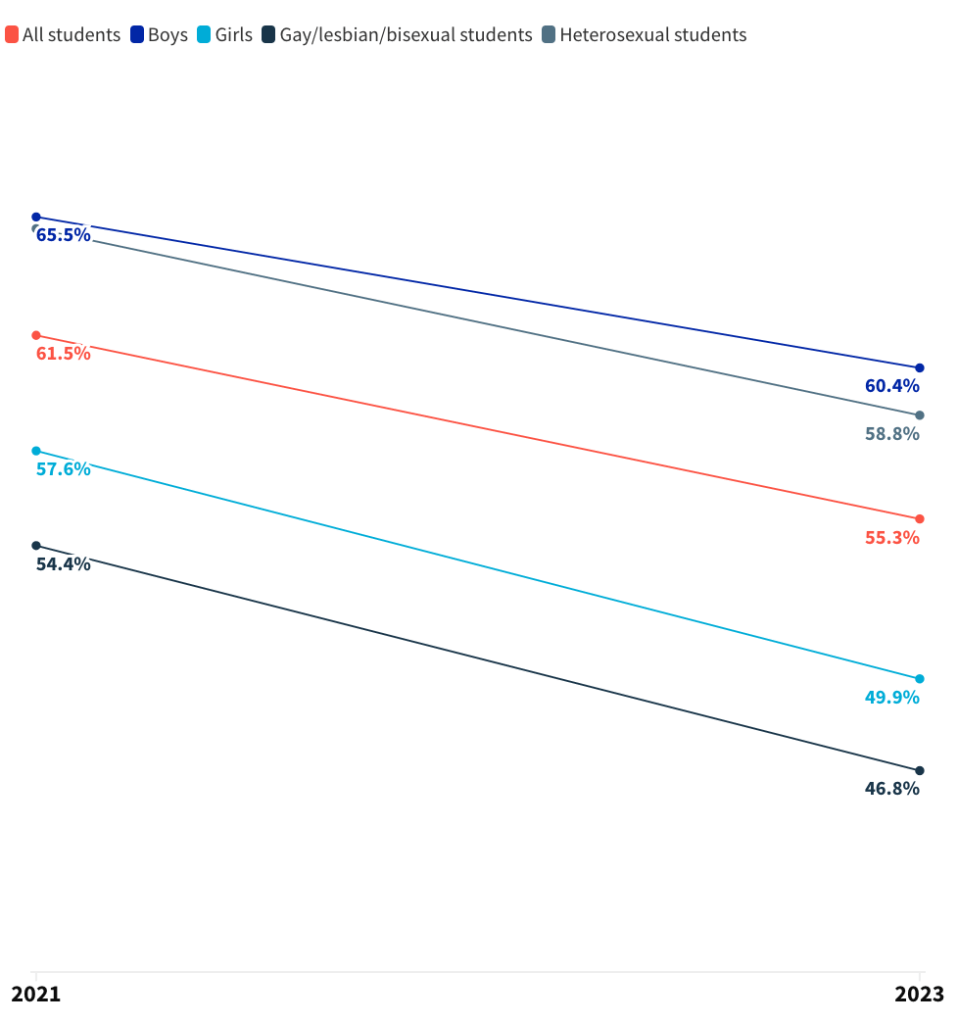

Moreover, access to supportive relationships is not equitably distributed: factors like race, socioeconomic status, parental education, gender, and immigration status shape the extent and quality of students’ peer relationships and networks—and, consequently, the social capital available to them. For instance, LGBTQ+ students are shown to be over 10 percentage points less likely than their heterosexual and cisgender peers to feel close to others at school, while girls also report lower relational connectedness than boys by more than 10 percentage points.

Addressing challenges of disconnection like these can certainly begin in classrooms and schools, but the external relationships in which students and schools are embedded—including those with mentors, families, and the broader community—are essential sources for the development of a whole system of supportive relationships. It’s important to note that students spend only 13% of their time in school, leaving 87% of their lives dependent on the relationships and environments beyond the classroom. Studies have shown that parental support strongly predicted lower levels of work avoidance, indicating that families of students play a primary role in keeping students motivated and goal-oriented. Furthermore, community conditions play a critical role in shaping students’ academic success, often rivaling or even outweighing the influence of family support. Children in high-poverty neighborhoods may be exposed to antisocial peers, leading to diminished academic progress—even in otherwise nurturing households. Yet, supportive communities with strong social cohesion and access to resources or social capital can buffer against these disadvantages, boosting early academic outcomes even in high-poverty areas. Together, these findings emphasize that relational networks—across school, home, and the community—lays the foundation for physical, mental, and academic support.

“Relational networks—across school, home, and the community—lays the foundation for physical, mental, and academic support.”

From this perspective, students’ relationships and networks can be seen as embedded in a broader, community-wide ecosystem rather than as a product of isolated institutions. When one part of that system falters, the entire structure can be weakened or even collapse. This underscores the importance of an interconnected educational ecosystem, where overlapping relationships between students, educators, families, and community members form a foundation for a supportive and effective learning environment.

What can be done to foster strong relationships in and beyond schools?

Developing a stronger, more equitable educational ecosystem begins with intentionally nurturing the relationships that fuel student learning and wellbeing. Fortunately, schools do not have to wait for large-scale reform: educators and communities are already implementing micro-innovations—small but powerful and tangible shifts in practices, routines, and resources—that foster connection and support. These include efforts to make visible the connections among students and between students and teachers; to deepen family-student ties through more inclusive school-family communication; and to expand community-student connections through partnerships with local organizations.

Connecting students and teachers

- Relationship mapping enables teachers to document and visualize the relationships and social networks among their students. In 5 Steps for Building & Strengthening Students’ Networks, Fisher and Charania describe several relationship building strategies including relationship mapping tools. Many of those tools begin with the development of color-coded lists that teachers can use to indicate students with whom they have strong relationships as well as those who may be more socially isolated. Teachers can also engage their own students in developing maps of the peer relationship in their class, and the same social network mapping strategy can be used to document students’ relationships beyond the school with members of their families as well as with mentors and members of community organizations and health and service agencies. As Fisher and Charania put it, “Not only does relationship mapping provide more detailed information regarding whom your students know and turn to—it can also surface relationships that you could enlist more deliberately to expand supports or opportunities at your institution.”

“Not only does relationship mapping provide more detailed information regarding whom your students know and turn to—it can also surface relationships that you could enlist more deliberately to expand supports or opportunities at your institution.”

- The Relationship Check Tool assesses the quantity of relationships and the quality of those relationships as well. The tool is a free survey offered by the Search Institute and discussed as well by Fisher and Charania. The survey is designed to support self-reflection and conversation to help practitioners, educators, and families assess where their connections with young people are strong and where they could grow. This tool helps adults gain insight by asking them to reflect on the quality of their relationships with youth, not as a formal assessment, but as a prompt for intentional dialogue and improvement. It is designed to spark meaningful conversations among peers or between adults and young people about the support, care, or challenge present in those relationships. While not built as a diagnostic instrument, the tool can empower users to identify strengths and gaps in their relational practice, creating awareness that can translate into more purposeful relationship-building in classrooms, schools, or home settings.

- Peer Partner programs take many different forms, but they generally involve connecting two (or more) students who support each other in one or more activities. In some cases, peers may support each other in carrying out a physical activity, like running, or in getting to school or showing up for extra-curricular activities or clubs. By engaging in shared activities, students can develop relationships with peers they might not normally come in contact with. Some programs also focus specifically on connecting students to support their academic work. For example, at Acton Academy, Running Partners are peer accountability partners who help one another set daily goals, review progress, and provide encouragement throughout the school day. Students begin each morning by articulating their goals with their running partner, who then checks in to hold them accountable and offer feedback—whether by reviewing an essay, asking clarifying questions, or challenging them to aim higher. In younger grades, teachers adapt the practice by forming “housemate” groups of four, which broaden perspectives and make feedback developmentally appropriate. According to Acton educators, running partners not only help students “hold each other to a high standard of work” but also become an emotional support system, cheering one another on and offering encouragement when motivation dips.

- Brief, reflective writing exercises can support students’ sense of belonging. In these exercises, students read first-person accounts from older peers describing common challenges—such as homesickness, academic struggles, or difficulty connecting with professors—and then reflect in writing on their own feelings and strategies for navigating similar experiences. The goal is to normalize these challenges and reassure students that feeling out of place is a typical part of the school experience. According to the researchers who have studied these exercises, students who participated reported feeling less anxious about fitting in and experienced slight improvements in academic performance, earning fewer Ds and Fs than peers who did not engage in the intervention.

Connecting students, schools, families, and communities

- App-based platforms provide a relatively new way to connect parents and teachers. Apps like ClassDojo, Seesaw, Remind, and ParentPowered allow educators to share updates, videos, and messages with families in real time, giving parents a window into classroom activities they might otherwise miss. Teachers use these apps to reinforce learning at home, provide reminders, and communicate about student progress, while students can showcase work directly to their families. As Helen Westmoreland, director of family engagement at the National PTA, explains, these apps are “a starting place for good family engagement, not the ending place,” emphasizing that the tools work best when paired with thoughtful in-person connections.

- Two-way (virtual) town halls were designed to give students and parents the chance to voice concerns, ask questions, and offer suggestions alongside updates from administrators. During the pandemic, these town halls were adapted from the usual, largely ceremonial, “parents’ nights”, at Knowledge and Power Preparatory Academy (KAPPA) in New York City to both learn from parents and students about their needs and to provide critical information about the schools’ response to the school closures. . These bi-monthly meetings became a critical means for understanding students’ social-emotional needs and academic challenges, allowing the school to make adjustments—such as changing start times to address students’ concerns about social distancing. Feedback from families also directly informed advisory lessons, social-emotional learning units, and academic goal-setting activities, ensuring programming responded to students’ needs.

- Newcomer Liaisons and Newcomer Coordinators provide support to recently arrived immigrant students and their families. Newcomer liaisons are individuals or teams who serve as a dedicated point of contact who can work with immigrant families on issues like enrollment, programming, communication, and bilingual services. They can help students navigate school systems and access resources such as healthcare and clothing. By centralizing support, the liaisons aim to reduce the burden on teachers, improve students’ access to services, and foster a more equitable and responsive learning environment, particularly for newcomers in historically under-resourced schools.

- Digital Directories have been created by organizations like Remake Learning to help students and schools connect with community members and organizations who can provide mentorship, apprenticeships and other learning opportunities. contact information for network members, programs, and organizations. At Remake Learning, the directory enables participants to see themselves as part of a larger network, access available resources, and browse calendars of events and engagement opportunities, strengthening connections across the ecosystem.

- Learning Festivals are events designed to bring together schools and other people and organizations to showcase some of learning opportunities across particular communities. For example, Remake Learning Days, launched initially in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 2015, have now expanded to 10 different regions in four countries. These festivals provide creative, immersive learning experiences across diverse settings—including libraries, tech centers, schools, museums, parks, and community centers—who focus on hands-on, and maker-based education. Beyond providing opportunities for students to find out about learning opportunities in their community, these festivals can also help to foster connections among schools and other organizations in their communities and strengthen the whole learning ecosystem.

By starting with micro-innovations like these for even one aspect of relationship building—supporting connections among students, between students and teachers or among students, schools and the wider community—schools can lay the groundwork for a system where every student is seen, supported, and connected.

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT)

The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT)