This blog by Melanie Ehren and Martijn Meetern was originally published by LEARN!. Ehren is a Professor in Educational Governance and Director of Research Intsitute LEARN!, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and Meeter is Full Professor, Faculty of Behavioural and Movement Sciences, Educational and Family Studies, LEARN!

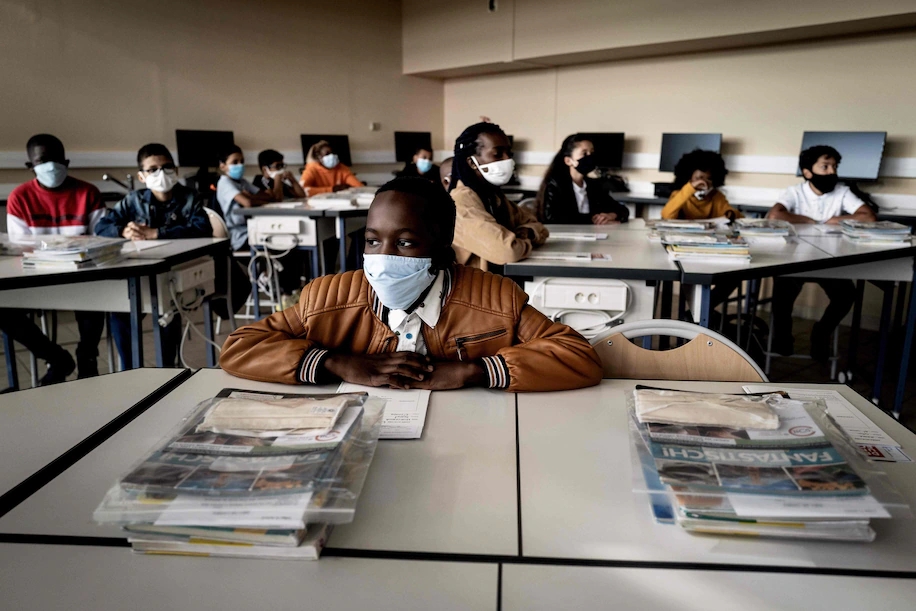

Increasing inequality

In many countries, COVID-related school closures affected already disadvantaged students most in their opportunities to learn and progress. In the Netherlands, the Inspectorate of Education raised the alarm over how the pandemic is leading to further inequality, with alarming numbers of students leaving primary education without the basic skills in arithmetic, reading and writing. As in many countries across the world, the Dutch government is developing new policies to address learning loss from COVID and ‘build back a better system’. These policies include funding for schools to organize targeted support for students in need (e.g. tutoring, remedial teaching) with further investments for schools serving a disadvantaged population. In addition, a government-wide investigation is now underway to better understand the root causes of educational inequality and how to make the education systems more responsive to policies addressing those root causes.

A decentralized system and a coordinated approach

Improving education from the top is not an easy task, given the highly decentralized nature of the education system in the Netherlands and the value placed on school autonomy. The OECD describes Dutch schools as having the highest autonomy internationally. Freedom of education has been the backbone of Dutch education for decades, and is a core value for many policymakers and practitioners working in education.

A more centralized and coordinated approach is, however, crucial to reduce inequality, given that differences in learning opportunities and outcomes often lie outside a school’s span of control. Examples are of parents’ free school choice, which leads to highly homogenous schools with a concentration of social, behavioural and learning problems in some schools, or the early tracking in secondary education which tends to disadvantage children from poorly educated and/or migrant backgrounds. Various studies have mapped out the causes and consequences of the high inequality in the Dutch system with one clear message: this is a complex problem because of its multidisciplinary nature (spatial, social, economic inequalities interact and reinforce each other) where any type of measure to improve education will have multiple outcomes, a high level of interconnectedness, and non-linear outcomes. The high complexity requires a coordinated approach that goes beyond individual interventions or programmes, but where the goal is to change how the whole education system operates to reduce inequality.

Where should we start when trying to address high inequality?

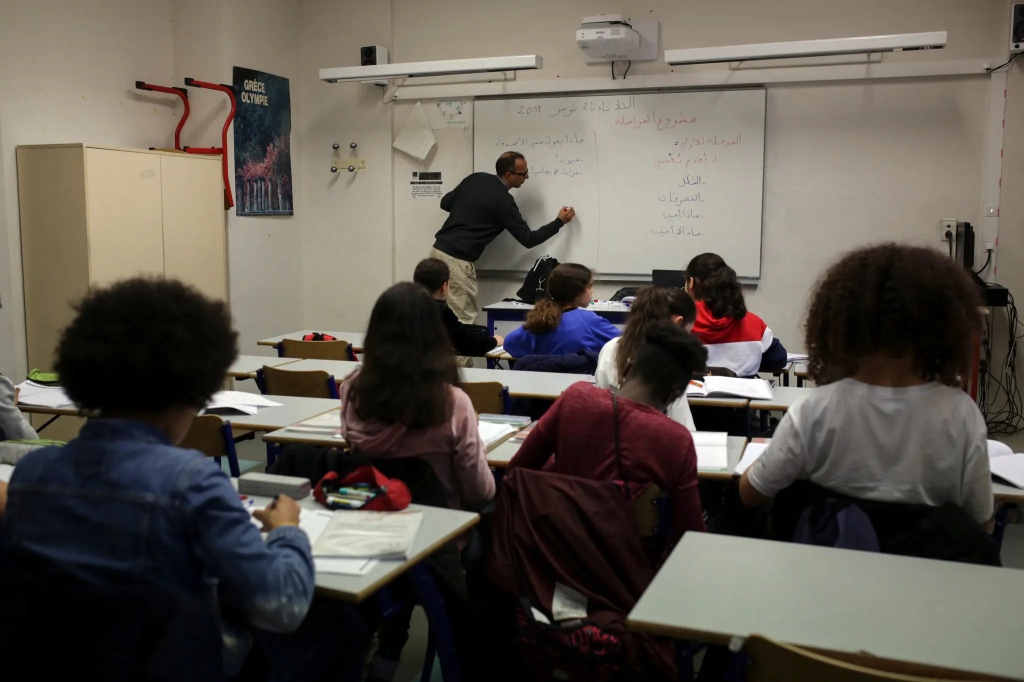

Ideally we want a set of interventions that have a multiplier effect where their collective impact on reducing inequality is greater than the sum of single activities. As good teachers and high quality teaching are the backbone of any education system, this is where we should start: We need to ensure that all school have sufficient high-quality teachers.

“The OECD TALIS report also indicates a sharp decline in the status of the teaching profession in the Netherlands… By reducing entry requirements, we unintentionally lower quality standards as well as the status of the profession.”

However, the Netherlands faces a large teacher shortage that will only become bigger in the future. Predictions are that secondary schools in 2023 will have a shortage of more than 1000 teachers with a further estimation of a shortage of 2600 fte in 2026, due to retirement. Certain subjects (Dutch, German, French, ICT, Mathematics, Science etc) will be particularly affected in the future, while schools in some urban areas in the country are already in constant crisis management to fill vacancies. Approximately 12% of primary schools in the large cities (e.g. Amsterdam) have permanent vacancies as teachers are moving to more affordable places to live and work. Even when a sufficient number of teachers enters the profession (which is unlikely given current student numbers on teacher education programmes), many of them leave due to high workload and stress, a lack of support and too much responsibility when starting to teach, an unsupportive school environment with too few opportunities for career progression and lack of communication with colleagues and school leadership. An average of 31% of beginning teachers in secondary education tend to leave teaching within five years of graduation.

Contradictory measures

The Ministry of Education has tried to increase the number of teachers by allowing schools to hire unqualified teachers while they train to be teachers on the job, but these teachers seem to be particularly prone to exit the profession. It’s also worth questioning this strategy for the message it sends to the profession at large: how should we understand the nature and status of teaching when we allow anyone with a degree in Higher Education to be a teacher? The Inspectorate of Education reports that an average of 7% of primary schools have unqualified teaching staff and this has detrimental consequences for the instructional quality and children’s learning outcomes. The OECD TALIS report also indicates a sharp decline in the status of the teaching profession in the Netherlands. This may well be an important factor in shortages, as low status affects the potential to recruit sufficient high quality teachers. By reducing entry requirements, we unintentionally lower quality standards as well as the status of the profession. Unfortunately, past policies have seen more of such inconsistencies, such as the introduction of a professional register which provides entry barriers but also increases the administrative workload of teachers without necessarily improving the overall quality of their work.

What can we do to increase the number of high quality and qualified teachers?

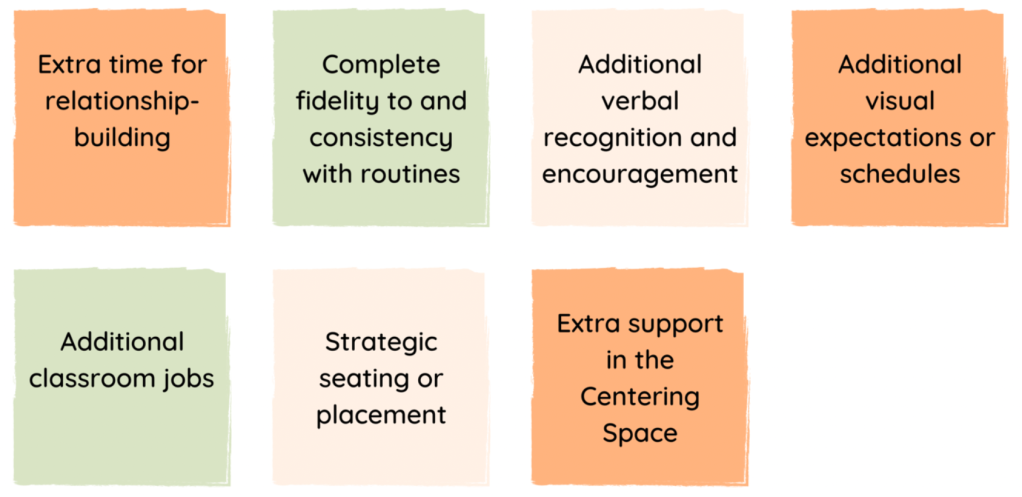

Various studies look at the types of interventions that can help build a strong and sufficiently large body of teachers. Here is a summary of the top 6:

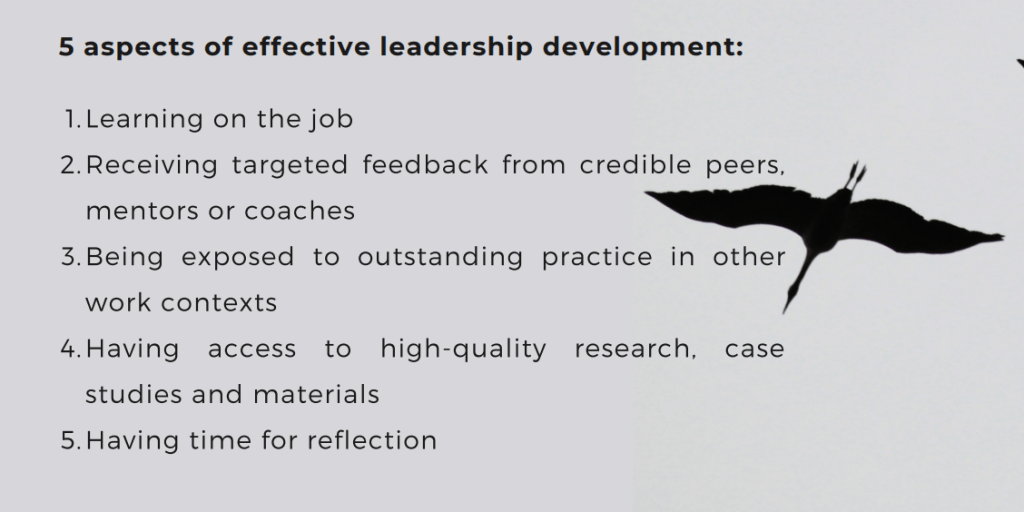

- Ensure high-quality school leaders. School leaders play a critical role in determining whether teachers are satisfied at work and remain at their school (Kraft et al, 2016), while their instructional leadership can improve the teaching in their school.

- Ensure a good working environment for teachers. Sims (2021) review of empirical literature stretching back 20 years suggests that the quality of the working environment in a teacher’s school is an important determinant of retention. A good working environment includes limited administrative workload and marking, collaboration with colleagues and having a manageable classroom of students in terms of their behaviour and teacher-student ratios. The school leader will have an important role in shaping these conditions of work, but external stakeholders (e.g. Inspectorates of Education) will also have a role to play.

- Ensure that new teachers are supported when starting teaching and receive feedback and coaching from experienced teachers in the school.

- Ensure teachers are paid more in the most difficult schools, in the most unaffordable areas to live in, and to teach the subjects that are least popular. Sims and Benhenda (2022) find that eligible teachers are 23% less likely to leave teaching in state funded schools in years they were eligible for payments with similar results reported in the US.

- Ensure that teachers have career prospects within the teaching profession, so that they don’t have to find these elsewhere. Singapore’s model is exemplary in this regard, while other countries (e.g. England) are also increasing the opportunities for a career in teaching (including formalizing professional development for the various stages).

- Ensure that teaching is valued as a profession and has high status in society (e.g. such as when entry requirements are high and the job is paid well).

And one final take-away message: policies and measures need to be coherent and well-aligned in both aiming to increase quality and quantity; compromising on either will not reduce inequality in the long term.