This week, Thomas Hatch continues his conversation with Keptah Saint Julien about the development of a Whole Child School Model at the Van Ness Elementary School, a District of Columbia Public School. In Part 1, Saint Julien talked about the beginnings of the Whole School Model, and some of the core components. Part 2 discusses some of the specific strategies for working with students who need additional support and some of the ways the model has changed over time. Keptah Saint Julien is a partner at Transcend with over a decade of experience in urban education. Saint Julien now works with her colleagues at Transcend to share the model in a Whole Child Collaborative in D.C. and in schools in Transcend’s national network. To support that work, Transcend recently received a $4 million dollar grant to study and scale the model in the DCPS and in Aldine ISD, in Texas.

Thomas Hatch: Last time, you talked about some of the key components that characterize the Whole Child School Model, can you talk a bit about the CARE plus and Boost strategies designed for students who need additional support?

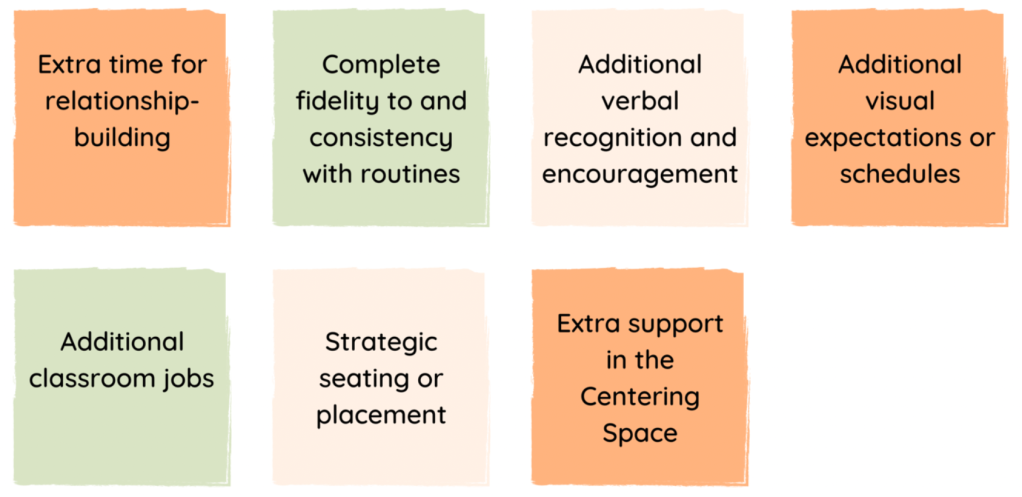

Keptah Saint Julien: For some students, CARE isn’t enough. They need additional supports to help them to be successful. For this we have both CARE Plus and BOOST. CARE plus means using CARE strategies with greater frequency or intensity (e.g. if a student needs more connections, they get extra connecting activities during the day, etc), but it also incorporates classroom strategies that teachers can implement to help these students. They may be academic, social or emotional.

We also have what is called TLC (Time, Love, and Connection), which gives students who need additional connection a daily opportunity to check in with an adult that they trust. BOOST also encompasses specific interventions like structured recess. Van Ness incorporated this practice for students who were being unsafe with their bodies. It’s important that every student has recess. Physical activity is an important way to alleviate stress. But if a student gets into an altercation, a staff member will pick up the students and take them to a space where they first talk about what happened. The staff member sits on the ground at the same level as the students, and then makes sure the students understand why they are in structured recess while giving the students a space to express their frustrations. At Van Ness, the staff member is usually a “behavior technician” who works to foster the development of positive behaviors and support students who are struggling. (Van Ness is one of several schools in the district that has behavior tech’s.) What’s beautiful about the model is that teachers do affirm student emotions. Students are allowed to be upset. Structured recess gives them the space to be upset, to express their frustrations and to reflect on how they can improve. After reflecting, the students build their skills with the behavior tech through practicing different recess games. That might be “This is how we play tag. We can practice and play.” So students get a chance to practice appropriate touch in tag and build the skills that they need in a structured setting, while still allowing for them to have recess and deepen a trusting relationship with an adult as well.

The last core component is Family Circle, which has a lot to do with the relationship building between families, teachers and staff members. Family Circle includes proactive relationship building as part of it, ongoing communication, family to family community building, academic partnering, and additional support, of course, for families as well. All these three parts – Family Circle, CARE, and Boost – make up the approach to well-being.

TH: That’s fascinating, such great examples of things like being at eye level with students. These are specific practices that really add up. The structured recess was a good example of something that’s changed or developed over time. What other tweaks or changes had to be made as the model developed?

KSJ: I would say the biggest shift in any school redesign is the shift that happens with adult mindsets, particularly when working with veteran teachers who have experience, knowledge and strategies that work for them. The key issue is helping them to see that we need to approach behavior and approach student well-being through relationship building and through proactive strategies, such as classroom greetings, intentional language and tone, and classroom design.

“The biggest shift in any school with any sort of redesign is the shift that happens with adult mindsets.”

TH: What has Van Ness done to support that shift?

KSJ: Cynthia sends many teachers to trainings and books studies. They do a lot of intentional professional development through organizations like Transcend. A good portion of her budget is allocated towards this.

TH: Van Ness has now achieved some success and been recognized both within DCPS and other places as a really exciting and promising model. I know that you and your colleagues at Transcend are working on sharing that success with other schools and communities. Can you talk a little bit about what you’ve learned as you’ve tried to spread the model? How the model has changed or how you’re thinking towards the model has changed?

KSJ: One of the first things that we’re committed to doing and that we’re working on is clarifying what’s core. It’s important that if a school says “I like the Whole Child Model and I really love what’s happening at Van Ness,” that they still recognize that each community is different, has different needs, students, and families. We are not trying to replicate Van Ness in every community, because the exact strategies are not going to work for every single community. But we know that student wellbeing is important for every school and every community. We’re trying to clarify what’s core. We’re testing and codifying some of the practices, and we’re also capturing the adaptations that are being done in different sites. Ultimately, we have this goal of increasing the impact of the model for schools and for school communities across the country. Right now, we have a first cohort that we’re still constantly learning from. We have also started an “Ignite Phase” for schools who are interested in the model. During this early phase, they explore questions like: What is wellbeing? What does wellbeing mean to me? What does it mean to my students? To my families? What do we know from research & best practice about factors that influence well-being? What are the strengths of our current approach? What are our needs? They start that listening process by interviewing and synthesizing information.

“We are not trying to replicate Van Ness in every community, because Van Ness is not going to work for every single community. But we know that student wellbeing is important for every school and every community.”

At the same time that we’re partnering with several schools in DCPS, we’re also working with schools around the country. For example, Carrollton Farmers Branch ISD, in the Dallas area, has identified one school who is piloting aspects of the model to determine how it might work there, and to see whether this is something that the district wishes to adopt more fully. Through an EIR grant we recently received, we’re able to expand to 10 schools in Aldine, Texas over the next several years. In addition, we’re partnering with a charter school in Memphis who wishes to adopt the model and potentially be a demonstration site for what this work can look like in Memphis. Even with this early expansion, we are very much in the learning phase. We learned a lot through our early work with Van Ness, and we’re learning a lot through our first cohort who are launching the model in their schools. It’s helping us learn what are the adaptations that we need to make in different school communities. One of the challenges arose when we launched with the first cohort because their first year of implementation happened during the pandemic. A lot of what they learned in the virtual world we are now transferring to classrooms, but it’s not always hitting the mark on the different elements of Strong Start for example. So now we have to go back and work on it again.

TH: Do you have another example like that – of something that’s not working that you have to change?

KSJ: Another thing that has been a struggle is structured recess. The issue is that there’s not a lot of capacity right now. As in many schools, a lot of teachers and staff members are unfortunately out. So, the schools just do not always have the people that they need in the building to run this type of intervention. Training and having a long-term sub who understands the model is a really important piece of the work to ensure students have a consistent experience. When you have a sub that comes in who doesn’t know the model, it can throw off the trajectory within a classroom and within the school culture. But right we just don’t have those long-term subs.

TH: These are great examples of both some of the changes that have been made and some of the challenges. As you look ahead, are there any key lessons, surprises, or things you didn’t know about when you went into this work that you’d want to share with others who are trying to develop more of a focus on well-being?

KSJ: I would like to touch on the family partnership aspect. We’re constantly going back to the drawing board and thinking about how to really meaningfully engage families in the work itself. That has been challenging, particularly now, given the circumstances that are happening in our very real world. It’s not always easy to partner up or communicate with families because families are busy and we’re busy. At the same time, families are our students’ first teachers. We aim to work in close partnership with them. It’s one thing, if I am teaching students how to self-regulate in their centering space and learn breathing, and teaching them focus. It’s even more powerful if, when they go home, they are practicing the same skills there. Without strong communication, there may be misalignment. The practices and teachings of social, emotional learning and wellness may not be consistent. We have to think about how we are working alongside families. What are their goals for their children? How are we helping them learn about the model and what’s happening in classrooms so that they are able to implement similar strategies at home and understand the language that students are using? Ongoing communication with families through meetings, newsletters, email and text has been really helpful. That is a part of Family Circle that is really going well. Parents are constantly looking out for further communication.

“We have to think about how we are working alongside families. What are their goals for their children? How are we helping them learn about the model and what’s happening in classrooms so that they are able to implement similar strategies at home and understand the language that students are using?”

TH: What are some of your hopes for the future?

KSJ: My personal hope is that we are codifying practices in ways that are accessible to everyone. There’s also a need for this type of work in upper grades. What would this look like in middle school? In addition to spreading this work at the elementary level, I hope we can codify and build out practices for middle schools and high schools.