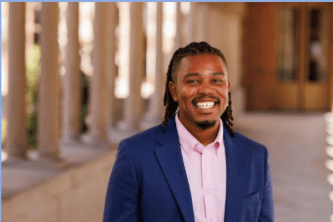

In this month’s Lead the Change (LtC) interview, David Osworth draws from his experiences in a research practice partnership and his work with improvement science as he discusses how to support leaders and center equity and justice in research and practice. Osworth is an assistant professor in the department of Educational Leadership and Cultural Foundations at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. His research focuses on race, class, and equity in educational leadership and policy. The LtC series is produced by Elizabeth Zumpe and colleagues from the Educational Change Special Interest Group of the American Educational Research Association. A pdf of the fully formatted interview is available on the LtC website.

Lead the Change (LtC): The 2025 AERA theme is “Research, Remedy, and Repair: Toward Just Education Renewal.” This theme urges scholars to consider the role that research can play in remedying educational inequality, repairing harm to communities and institutions, and contributing to a more just future in education. What steps are you taking, or do you plan to take, to heed this call?

Dave Osworth (DO): I appreciate this year’s AERA theme. I think a common pitfall for the academy is to focus exclusively on the creation of new knowledge without thinking about how this knowledge is relevant to the everyday work of educators or can help to make schooling a more equitable space. I have at times been guilty of staying exclusively in the theoretical without thinking about the transition to the practical. AERA’s theme calls upon us to think about the ways in which our research can lead to action.

One way that I am trying to respond to this call is by examining the ways in which research practice partnerships (RPP) may help to drive leadership capacity within a school district. For example, I have been part of an RPP between an R1 university and a large school district focused on fostering leadership capacity. RPPs are intended to be long term collaborations between researchers and practitioners involving boundary spanning through high levels of communication and the development of strong trust. With this RPP, like others, the research process is entwined with practice. Additionally, we have made sure that this partnership is very responsive to the needs of the district. As such we have found that at times it is important to be flexible and willing to explore how we might help address the additional needs of the district beyond the initial problem of practice. This flexibility has helped to support the longevity of the partnership and has resulted in new areas of work that supports the needs of the district while providing ample opportunity for university faculty to engage in scholarship.

AERA’s theme also calls upon us to think about the historical contexts of education. It is easy to fall into a pattern of focusing on the present problem of practice without situating it historically. As a scholar, I identify with post-critical approaches (see Anders & Noblit, 2024). This means that, as I apply my scholarship to educational leadership and policy, I try to think about the specific context that has shaped a current problem of practice. In practice, this can involve infusing historiographic works into my literature reviews, using the history of education to inform the context of my current scholarship. For example, in one of my current studies, I am examining the discursive practices of state policy actors as they debate anti-LGBTQ policy in North Carolina. My co-author and I situate this within an historical framing to understand how these attacks against LGBTQ individuals aren’t necessarily “new” or “unprecedented” but are a form of retrenchment. Retrenchment refers to a process through which, after progress has been made with regards to “rights,” a countermovement brings in more oppressive policies that move that progress back (see Crenshaw, 1988). We argue that by situating work historically, we can identify patterns in which communities resisted these oppressive policies (Osworth & Edlin, in progress).

“Attacks against LGBTQ individuals aren’t necessarily ‘new’ or ‘unprecedented’ but are a form of retrenchment.”

LtC: Your work has explored the policy implications of methods of continuous improvement, such as improvement science, that have been spreading in recent years. What are some of the major lessons that practitioners and scholars of Educational Change can learn from your work?

DO: Policymakers often think about improvement in terms of identifying what works in general, based upon randomized control trials (RCT), often seen as a gold standard in certain fields. This prototypical approach to research, however, may not always be possible and/or ethical in educational settings. Improvement science offers a different approach as a type of continuous improvement that aims to systematically solve complex problems of practice. The promise of improvement science lay in how it involves looking at the context of problems of practice and utilizing iterative approaches to address problems involving a feedback loop that allows interventions to be tested and adjusted (Bryk et al., 2015; Hinnant-Crawford, 2020). While traditional thoughts about improvement may assume that a “proven” intervention will be applied and if improvement does not occur it is because the intervention wasn’t done with fidelity. By contrast, improvement science recognizes the particularities of a problem within that specific context that must be considered to know how to solve it.

I have studied improvement science primarily in relation to its connection with the federal policy, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). ESSA, passed during the second Obama administration to replace No Child Left Behind, provides guidance to state education agencies about criteria are required to be included in their state accountability policies to be eligible for certain federal funding packages. In Cunningham and Osworth (2023), we classified 52 state accountability plans—this includes 50 states, Washington D.C. and Puerto Rico— based on their presence of improvement science language. We found that many state ESSA plans included language about “continuous improvement,” but this appeared more like a buzzword. Only a few highlighted specific improvement science approaches (e.g., Hawaii or Washington), and hence the true commitment to improvement science approaches within state education agencies was unclear (Cunningham & Osworth, 2023, 2024a).

We argue that district leaders can leverage improvement science while aligning with many states’ expectations of continuous improvement. Improvement science recognizes the need for a context-specific approach to improvement (Cunningham & Osworth, 2024b). Because not all districts within a state are the same, district leaders can use improvement science to identify and address context-specific problems while meeting the requirements of state-level ESSA plans (Cunningham & Osworth, 2024a).

LtC: Your research has examined leadership preparation in the context of research-practice partnerships. What might practitioners and scholars take from this work to foster better school systems for all students?

DO: Future school leaders need strong foundational preparation to develop confidence to be change agents to make schooling better for all children. In the RPP mentioned above, researchers at an R1 university collaborated with a large school district to intentionally design a leadership preparation program for a district-specific M.Ed. cohort at the university. As part of that RPP, in Osworth et al. (2023), I studied this leadership preparation effort using a powerful learning experiences (PLE) framework (see Cunningham et al., 2019; VanGronigen et al., 2019; Young et al., 2021). The PLE framework provides 10 characteristics that help to drive adult learning in leadership preparation programs. In this interview-based study, we found that the partnership specifically brought to the forefront certain PLEs—including providing authentic learning, building confidence, engaging in critical reflection, and sense making (Osworth et al., 2023). These results suggest that long-term and trusting partnerships like this may provide intentional access to practical experiences and supportive spaces that help to develop strong aspiring leaders.

“Future school leaders need strong foundational preparation to make schooling better for all children.”

I think that one of the most salient takeaways is that a collaborative partnership like this can strengthen graduate programs’ relevance and fit to the specific needs of districts. Through our partnership, the M.Ed. program underwent a redesign in response to district feedback, involving revamped coursework that included changes to required readings and key assessments (Osworth et al., under review). While leadership curriculum stayed relevant to national standards, the cohort could make real-time connections to their district context collectively, drawing on similar frames of reference and allowing for greater confidence in how the course content related to the practice of school leadership. Furthermore, because the partnership is characterized by a high level of communication, faculty could incorporate district-specific examples using district data (Osworth et al., under review).

Leadership matters in the context of student success and wellbeing (Grissom et al., 2021), and such partnerships provide opportunities for leaders to be prepared in a way that meets the needs of students. However, it is important to note that, to be effective, partnerships like this are time-intensive and require resources to be committed by both partnered organizations. For instance, attention to the needs of both organizations requires attention to multiple voices, which often involves a high level of planning and a time commitment by liaisons from both organizations (Osworth et al., under review).

LtC: Educational Change expects those engaged in and with schools, schooling, and school systems to spearhead deep and often difficult transformation. How might those in the field of Educational Change best support these individuals and groups through these processes?

DO: The current policy landscape is quite hostile towards educators engaging in meaningful change, especially regarding work surrounding diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). In the current times, many educators are understandably worried about anti-DEI policies and their repercussions. These policies are often under the guise of attacking the teaching of critical race theory, that ultimately make it difficult to engage in DEI work. The law school at the University of California, Los Angeles has a center that is tracking these current policies (CRT Forward, 2025). While many of these policies are challenging for states to enforce, they often include threats to funding as recourse (Martínez et al., 2023). Whether real or imagined, such policies create a sense of surveillance, which can control individuals’ behavior and becomes coercive in nature (Foucault, 1995).

To support educators committed to educational change, I think that scholars in the field of Educational Change need to be strategic in how we engage in work that centers equity. We need to continue to leverage tools from “controversial” theories (e.g., critical race theory, culturally responsive pedagogy, historical materialism, or humanizing pedagogies), but rethink about how we package them. We can help educators continue to center equity and justice without using the buzzwords so that they can navigate the current political landscape which has attacked allegedly controversial topics in school (CRT Forward, 2025).

By avoiding triggering buzz words, however, the goal is not to give into, but guard against, the chilling effect that can come from such policies. There are individuals who would like to opt out of the work of meaningful educational change, who will find it easy to cite these policies as the reason to do so. We should ensure that educators continue to engage with data that shows the persistence of racial disparity in our public schools to be at the crux of the change that is needed in education.

LtC: Where do you perceive the field of Educational Change is going? What excites you about Educational Change now and in the future?

DO: I think the field of Educational Change, now more than ever, needs to double down on efforts to center equity at the heart of our work. Equity poses what social scientists have called “wicked problems,” describing societal problems that tend to be both complex and heavily contested (Rittel & Webber, 1973). Rittel and Webber (1973) argue that traditional science tends to be insufficient to figure out how to solve wicked problems. Such problems, rather, require a commitment from the field to engage with and shape the debates around them.

I am excited about the potential for collaborative and community-engaged work to tackle “wicked” problems in education. The backlash against DEI has become a key wicked problem that requires sustained engagement. The backlash targets all non-dominant identity groups; this includes ability, class, gender, language, race, and sexuality (to name a few). This period of retrenchment, as described above, can make it challenging to support all students in creating a more socially just schooling environment. I see a major purpose of my work, and the work of the field, to be to serve as resistance this retrenchment and continue to advance a justice-oriented agenda that serves our children and fulfills the democratic promise of our schools.

I’m also excited for the opportunities in Educational Change to engage in theoretically rich work that is also relevant to practice. An often-expressed concern is that theory and practice don’t align or that theory-heavy research cannot be applied practically. In contrast, I think many critical theories offer valuable analytic insights for navigating the current moment. Indeed, educational change is entering an exciting moment to engage in praxis— to reflect upon action to connect theory to practice. What excites me most is the opportunity to engage in praxis through conducting research that is theoretically deep and involves critical reflection on how we engage in action related to that theory.

References

Anders, A. D. & Noblit, G.W. (2024). Postcritical ethnography. In A.D. Anders & G.W. Noblit (Eds.) Evolutions in critical and postcritical ethnography: Crafting approaches (pp. 1-20). Springer.

Bryk, A.S. (2020). Improvement in action: Advancing quality in America’s schools. Harvard Education Press.

Bryk, A.S., Gomez, L., Grunow, A., & LeMahieu, P.G. (2015). Learning to improve: How America’s schools get better at getting better. Harvard Education Press.

Crenshaw, K. (1988). Race, reform, and retrenchment: Transformation and legitimation in antidiscrimination law. Harvard Law Review, 101(7), 1331-1387.

CRT Forward. (2025). CRT Forward. Retrieved from https://crtforward.law.ucla.edu/

Cunningham, K.M.W., VanGonigen, B.A., Tucker, P.D. & Young, M.D. (2019). Using powerful learning experiences to prepared school leaders. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 14(1), 74-97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1942775118819672

Cunningham, K.M.W. & Osworth, D. (2023). A proposed typology of states’ improvement science focus in their state ESSA plans. Educational Policy Analysis Archives, 31(37), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.31.7262

Cunningham, K.M.W. & Osworth, D. (2024a). Improvement science and the Every Student Succeeds Act: An analysis of the consolidated state plans. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 23(4), 955-972. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2023.2264924

Cunningham, K.M.W. & Osworth, D. (2024b). Policy considerations for continuous improvement. In Anderson, E., Cunningham, K. M. W. & Eddy-Spicer, D. H. Leading continuous improvement in schools: Enacting leadership standards to advance educational quality and equity. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003389279-13

Foucault, M. (1995). Discipline and Punish: The birth of the prison. Vintage Books.

Grissom, J.A., Egalite, A.J. & Lindsay, C.A. (2021). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. [White Paper] The Wallace Foundation, New York.

Hinnant-Crawford, B. (2020). Improvement science in education: A Primer. Myers Education Press.

Martínez, D.G., Osworth, D., Knight, D. & Vasquez Heilig, J. (2023). Southern hospitality: Democracy and school finance policy praxis in racist America. Peabody Journal of Education, 98(5), 482-499.

Osworth, D. & Cunningham, K.M.W. (2022). Improvement science and the Every Student Succeeds Act: An analysis of state guidance documents. Planning and Changing, 51(1/2), 3-19.

Osworth, D., Cunningham, K.M.W, Hardie, S., Moyi, P., Osborne Smith, N. & Gaskins, M. (2023). Leadership preparation in progress: Evidence from a district-university partnership. Journal of Educational Administration, 61(6), 682-697. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-01-2023-0009

Osworth, D., Cunningham, K.M.W., Hardie, S., Moyi, P., Osborne Smith, N. & Gaskins, M. (Under Review). Boundary spanning, partnerships, and educational leadership: How a district-university partnership fostered organizational learning.

Osworth, D. & Edlin, M. (In Progress). The political construction of “don’t say gay”: A critical discourse analysis of North Carolina state legislators.

Rittel, H.W.J. & Webber, M.M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155-169.

VanGronigen, B.A., Cunningham, K.M.W., & Young, M.D. (2019). How exemplary educational leadership preparation programs hone the interpersonal-intrapersonal (i2) skills of future leaders. Journal of Transformative Leadership and Policy Studies, 7(2), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.36851/jtlps.v7i2.503

Young, M.D., Cunningham, K.M.W., VanGronigen, B.A., & O’Doherty, A. (2021). Transformational leadership preparation in a post-COVID world: U.S. perspectives. eJournal of Educational Policy, 21(1), 1-15.