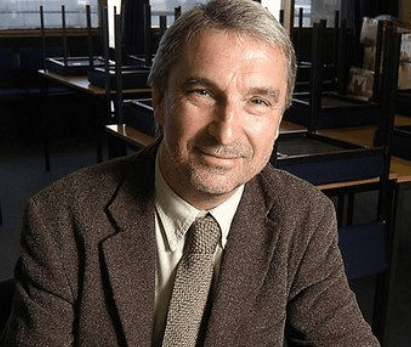

This week, Mel Ainscow discusses some of the key insights from his new book Reforming Education Systems for Inclusion and Equity. Ainscow is Emeritus Professor, University of Manchester, Professor of Education, University of Glasgow, and Adjunct Professor at Queensland University of Technology.

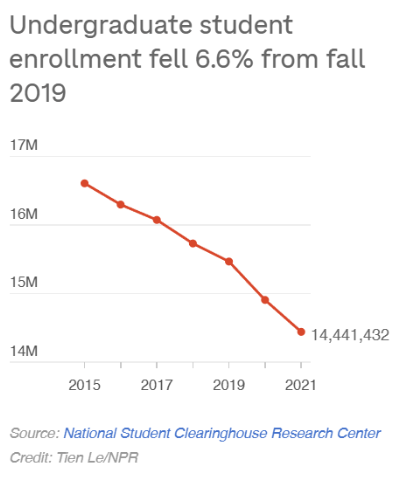

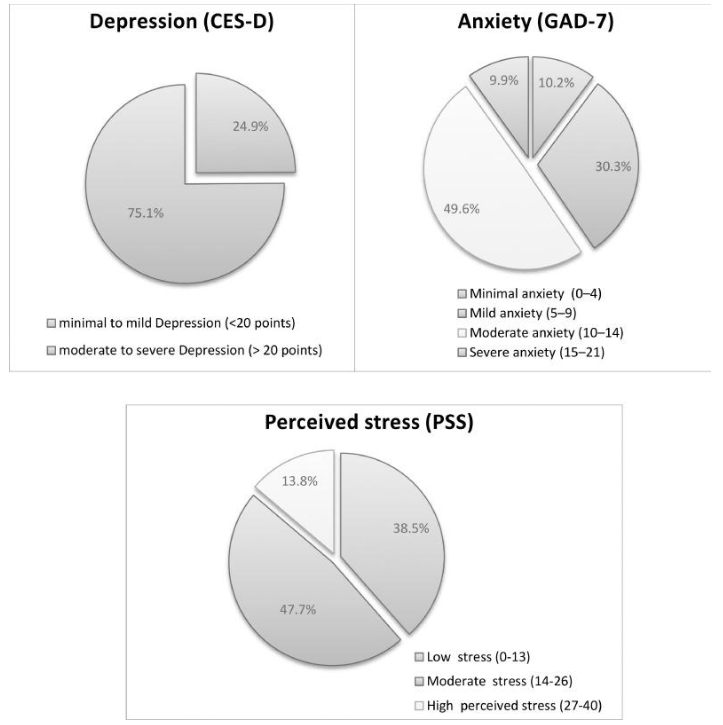

What’s the greatest challenge facing education systems around the world? Finding ways of including and ensuring the progress of all children in schools. In economically poorer countries this is mainly about the millions of children who are not able to attend formal education. Meanwhile, in wealthier countries many young people leave school with no worthwhile qualifications, whilst others are placed in special provision away from mainstream education and some choose to drop out since the lessons seem irrelevant. Faced with these challenges, there is evidence of an increased interest internationally in the idea of making education more inclusive and equitable. However, the field remains confused as to the actions needed in order to move policy and practice forward.

What’s the greatest challenge facing education systems around the world? Finding ways of including and ensuring the progress of all children in schools.

Reforming education systems

Over the last thirty years or so I have had the privilege of working on projects aimed at the promotion of inclusion and equity within education systems, in my own country and internationally. This leads me to propose a radical way of addressing this important policy challenge. This thinking calls for coordinated and sustained efforts within schools and across education systems, recognising that improving outcomes for vulnerable learners is unlikely to be achieved unless there are changes in the attitudes, beliefs and actions of adults. All of this echoes the views of Michael Fullan, an internationally recognised expert on educational change, who argues: “If you want system change you have to change the system!”

“If you want system change you have to change the system!”

In Reforming Education Systems for Inclusion and Equity, I suggest six key ideas that can be used to guide reform efforts:

- Inclusion and equity should be seen as principles that inform educational policies. These principles should influence all educational policies, particularly those that are concerned with the curriculum, assessment processes, teacher education, accountability and funding.

- Barriers to the presence, participation and achievement of learners should be identified and addressed. Progress in relation to inclusion and equity requires a move away from explanations of educational failure that focus on the characteristics of individual children and their families, towards an analysis of contextual barriers to participation and learning experienced by learners within schools. In this way, those students who do not respond to existing arrangements come to be regarded as ‘hidden voices’ who can encourage the improvement of schools.

- Schools should become learning communities where the development of all members is encouraged and supported. Reforming education systems in relation to inclusion and equity requires coordinated and sustained efforts within schools. Therefore, the starting point must be with practitioners: enlarging their capacity to imagine what might be achieved and increasing their sense of accountability for bringing this about. The role of school leaders is to create the organisational conditions where all of this can happen.

- Partnerships between schools should be developed in order to provide mutual challenge and support. School-to-school collaboration can strengthen improvement processes by adding to the range of expertise made available. In particular, partnerships between schools have an enormous potential for fostering the capacity of education systems to respond to learner diversity. More specifically, they can help to reduce the polarisation of schools, to the particular benefit of those students who are marginalised at the edges of the system, and whose progress and attitudes are a cause for concern.

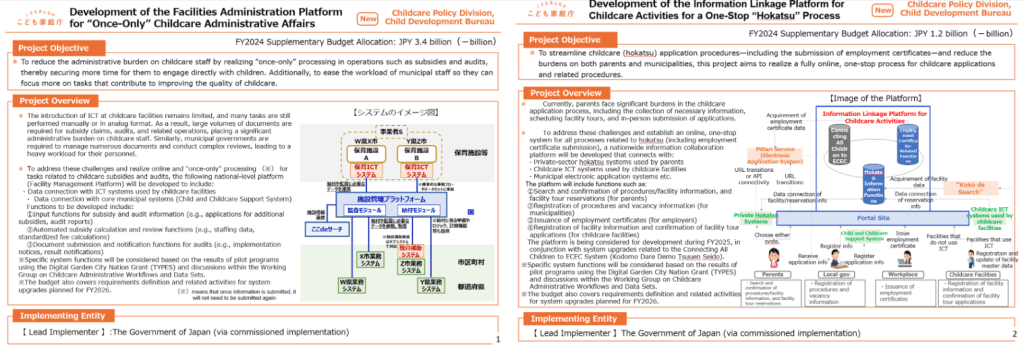

- Families and other community partners should be encouraged to support the work of schools. The development of education systems that are effective for all children will only happen when what happens outside as well as inside a school changes. Area-based partnerships are a means of facilitating these forms of cooperation. School leaders have a crucial role in coordinating such arrangements, although other agencies can have important leadership roles.

- Locally coordinated support and challenge should be provided based on the principles of inclusion and equity. The presence of experienced advisers who can support and challenge school-led improvement is crucial. There is an important role for governments in creating the conditions for making such locally led improvements happen and providing the political mandate for ensuring their implementation. This also means that those who administer local education systems have to adjust their priorities and ways of working in response to improvement efforts that are led from within schools.

Using evidence

Evidence is the life-blood of inclusive educational development. Therefore, deciding what kinds of evidence to collect and how to use it requires considerable care, since, within education systems, what gets measured gets done. This trend is widely recognised as a double-edged sword precisely because it is such a potent lever for change. On the one hand, data are required in order to monitor the progress of children, evaluate the impact of interventions, review the effectiveness of policies, plan new initiatives, and so on. On the other hand, if effectiveness is evaluated on the basis of narrow, even inappropriate, performance indicators, then the impact can be deeply damaging.

The challenge, therefore, is to harness the potential of evidence as a lever for change, whilst avoiding these potential problems. This means that the starting point for making decisions about the evidence to collect should be with agreed definitions of inclusion and equity. In other words, we must measure what we value, rather than valuing what can more easily be measured. Therefore, evidence collected within the education system needs to relate to the presence, participation and achievement of all students.

“[I]nclusion and equity should not be seen as a separate policy. Rather, they should be viewed as principles that inform all national policies”

Implications

These ideas are guided by a belief that inclusion and equity should not be seen as a separate policy. Rather, they should be viewed as principles that inform all national policies, particularly those that deal with the curriculum, assessment, school evaluation, teacher education and budgets. They must also inform all stages of education, from early years through to higher education. In this way inclusion and equity must not be seen as somebody’s job. Rather, it is reform agenda that must be the responsibility of everyone involved in providing education.