This week’s post features a follow-up interview with Hirokazu Yokota, discussing his experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan, as a parent, education policymaker and now government officer at Japan’s newly established Digital Agency. Yokota was a principal architect of two recent policies: the Basic Act on the Formation of a Digital Society, which set basic principles to transform Japan by cross-ministerial policy making and passed the Japanese Diet on May 2021; and the Priority Policy Program for Realizing Digital Society, which include policy measures for the government to implement and got cabinet approval in December 2021. Recently, he published an article on school leadership in Japan in the International Journal of Leadership in Education. The post shares his own views and does not necessarily represent official views of DA and the Japanese government.

IEN: What has been happening with you and your family this year? How does this compare to what you told us in your previous post at the beginning of the pandemic (A view from Japan: Hirokazu Yokota on school closures and the pandemic)?

Hirokazu Yokota: Too many changes to remember, I would say… the positive thing is that I and my family are still doing well and safe, which is the most important. My working style has changed a lot. I still work from home two to three days a week, which means I have more time to spare with my kids. Almost every meeting, including the ones with the Minister, happens online, which was almost inconceivable pre-pandemic to me. The society now has more tolerance for that flexible style, as it found paper-based and face-to-face working style infeasible in the presence of this lasting pandemic.

The other side? My six-year-old daughter suddenly said she wanted to wear a mask on top of another and cried (she always wears one when going outside). She, by watching TV news etc., was kind of afraid of getting Omicron. I couldn’t just say getting it isn’t a big deal. Kids absorb and think much more from what they see in the world than we imagine. As a parent, I have to balance two seemingly-conflicting demands – providing my kids with real-life, authentic opportunities to interact with a variety of people, and preventing the infection of Covid-19 at the same time. This is a very challenging act of parenting, and to be honest, I have not found any solid answer here.

“As a parent, I have to balance two seemingly-conflicting demands – providing my kids with real-life, authentic opportunities to interact with a variety of people, and preventing the infection of Covid-19 at the same time. This is a very challenging act of parenting”

IEN: It’s interesting to see that you’re now working at a new governmental agency. What is the Digital Agency and what does it have to do with this pandemic?

HY: The Covid-19 pandemic was a wake-up call for Japan’s digital transformation. Management of the health crises was hampered by outdated and cumbersome administrative systems. Additionally, in the past, each ministry, agency, and local government has been promoting digitalization separately, which resulted in 1,700 local governments with 1,700 systems: procured and managed separately with dispersed responsibility. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the ineffectiveness of this practice.

As a response, in September 2020, then Prime Minister SUGA Yoshihide made the digitalization of Japan one of his top priorities. Accordingly, the Digital Agency (DA) was established at an incredible speed and launched in September 2021. DA has strong powers of comprehensive coordination, such as the power to make recommendations to other ministries and agencies.

What is particularly interesting is that of the about 600 DA officers, a third (some 200) are coming from the private sector, which creates a mixed organizational culture of thorough coordination of stakeholder interests in the public sector and agile/flexible decision making in the private sector. New challenges every day, but a very inspiring working environment. Given that I’ve mainly worked within the education sector it really helps to broaden my perspective.

IEN: In the field of education specifically, you previously mentioned that the Japanese government planned to implement “one device per student” initiative. What has worked, and what has been problematic?

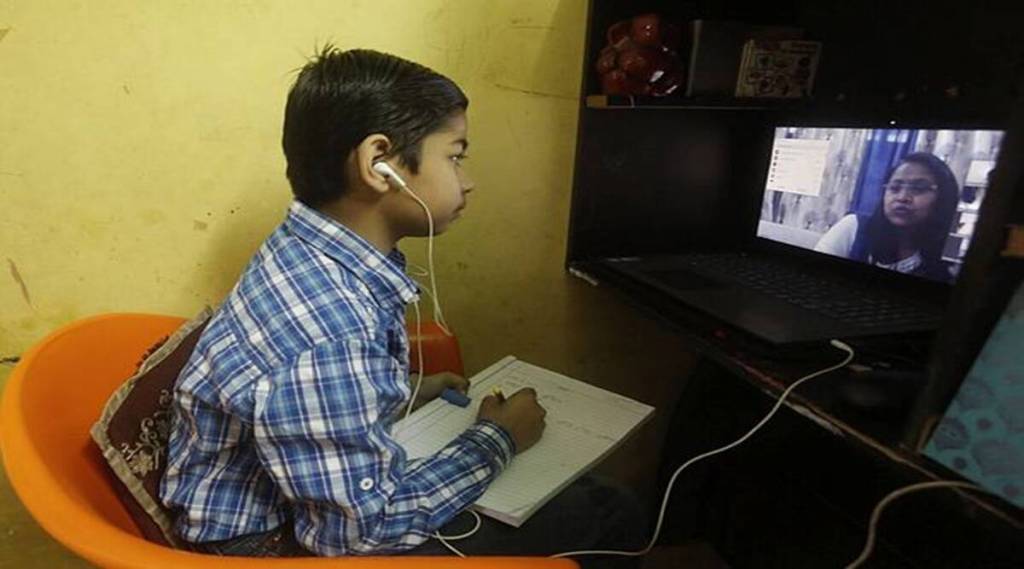

HY: The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) has started the GIGA (Global and Innovative Gateway for All) School Program to make certain equitable and individually optimized learning by providing one computer per student and high-speed Internet for schools, which originally aimed at one device per student by the end of FY 2023. In the face of the COVID-19 crisis, it was accelerated and strengthened, with the distribution of one device per student almost completed by July 2021. About 461 billion yen (some 4 billion US dollars) in total was allocated for that purpose, which obviously was a huge investment.

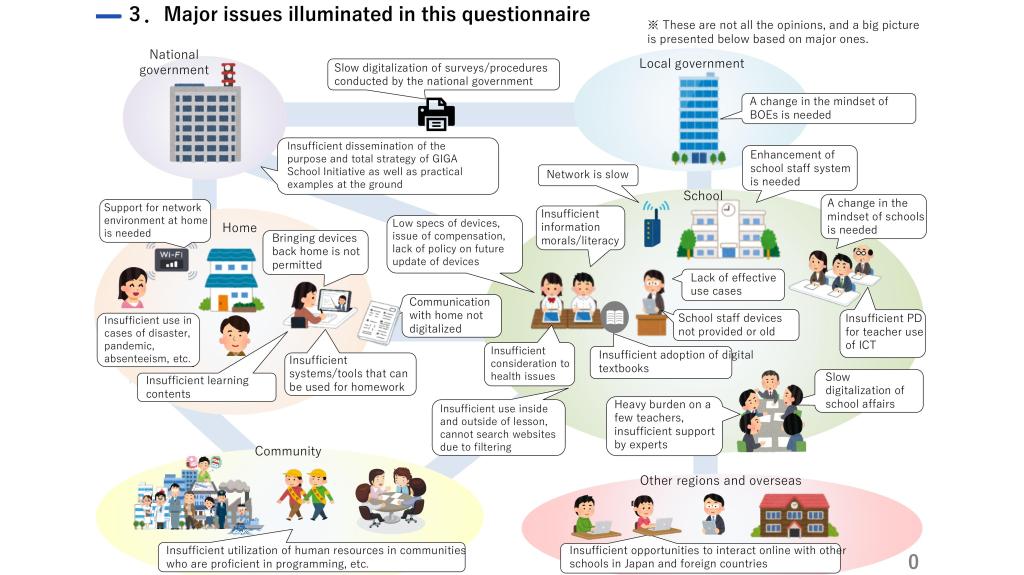

However, when I collected voices from 217,000 students and 42,000 educators through an online questionnaire on this GIGA School Initiative in July 2021, it turned out that there were many problematic issues on the ground – including slow networks, slow digitalization of school affairs, school staff that never got devices, equipment that was too old or insufficient for use inside and outside of the classroom as well as insufficient support by experts. In terms of policy implementation, just distributing a subsidy does not necessarily guarantee that ICT devices are actually used, and there are many steps to be taken before these are put into daily use like pencils and notebooks.

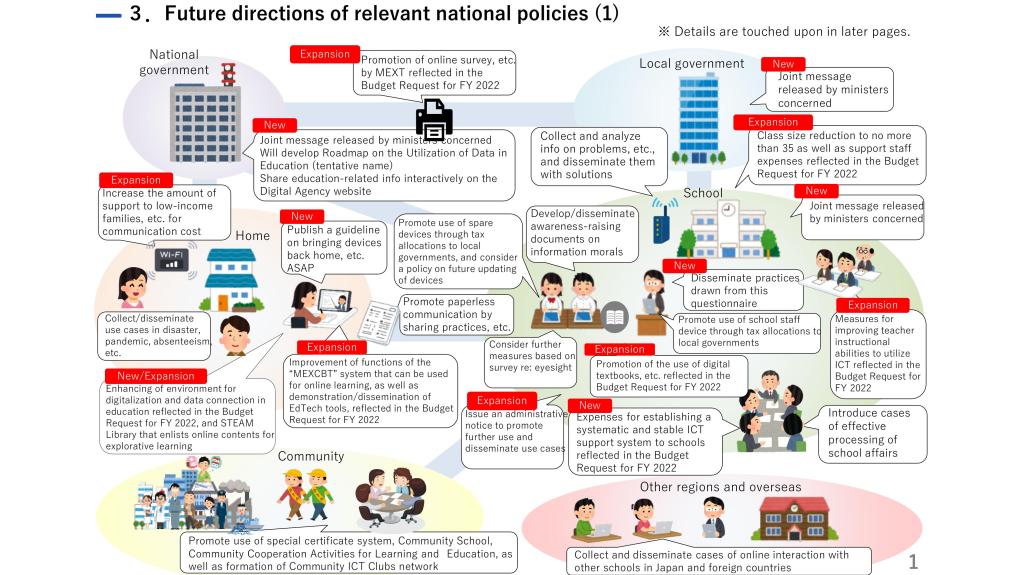

In order to fill in this gap between policy and practice, the Digital Agency, with the ministries concerned, released a joint message to students and educators, and presented their responses in the form of future directions of relevant policies. Some of them actually led to subsequent supplementary budget items approved in December 2021.

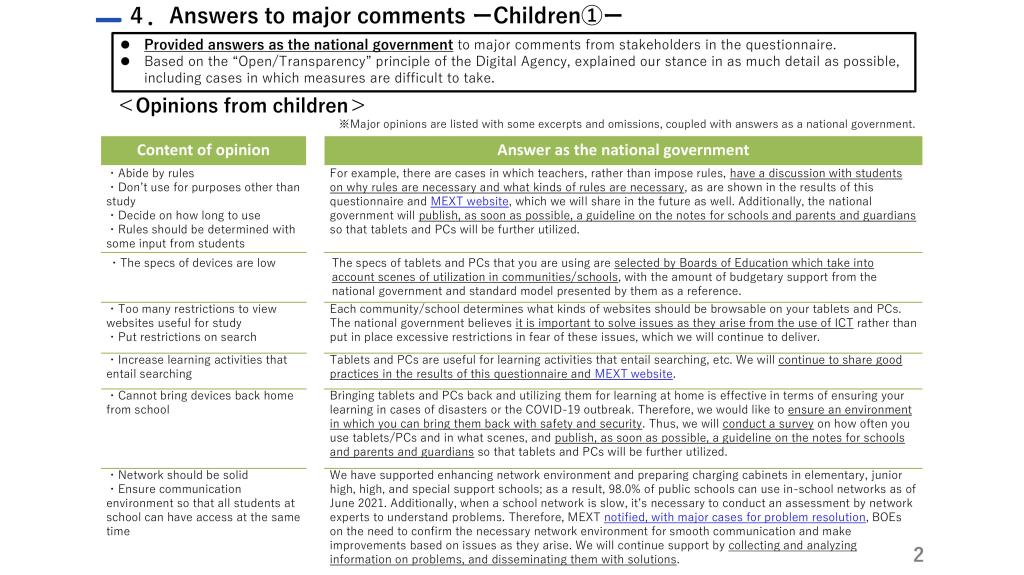

Additionally, we took the comments from students and educators very seriously, and based on the “Open/Transparency” principle of DA, we explained our stance in as much detail as possible, including cases in which measures are difficult to take. This, I believe, is very meaningful as a new trial of policy refinement based on voices from the ground, where digital plays a significant role in reaching out to people/users.

IEN: This initiative is still in progress, but what’s next?

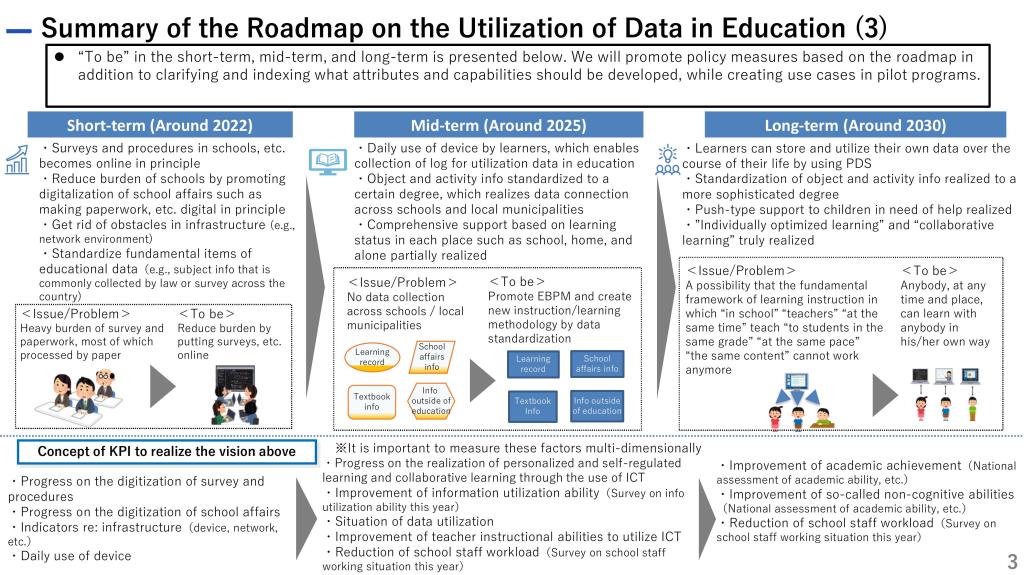

HY: Yes, when we think of three phases of digital transformation – (1) digitization, (2) digitalization, and (3) digital transformation, the current movement is mostly in phase (1) (digitization). However, the potential of digital technology goes far beyond taking paper and face-to-face processes and putting them online; it also lies in promoting student-centered learning as well as providing wraparound and push-type services to children by connecting a variety of data. Therefore, recently (in January 2022), DA and the ministries concerned published “Roadmap on the Utilization of Data in Education.” First, we set the mission of digitalization in education as “a society where anybody, at any time and place, can learn with anybody in his/her own way,” and established “three core goals” – enriching the (1) scope, (2) quality, and (3) combination of data – for realizing that mission. Issues and necessary measures, such as standardizing data in education, the way the creation of the platform in the field of education ought to be, determining rules/policies for the utilization of data in education, are clarified with a timeline.

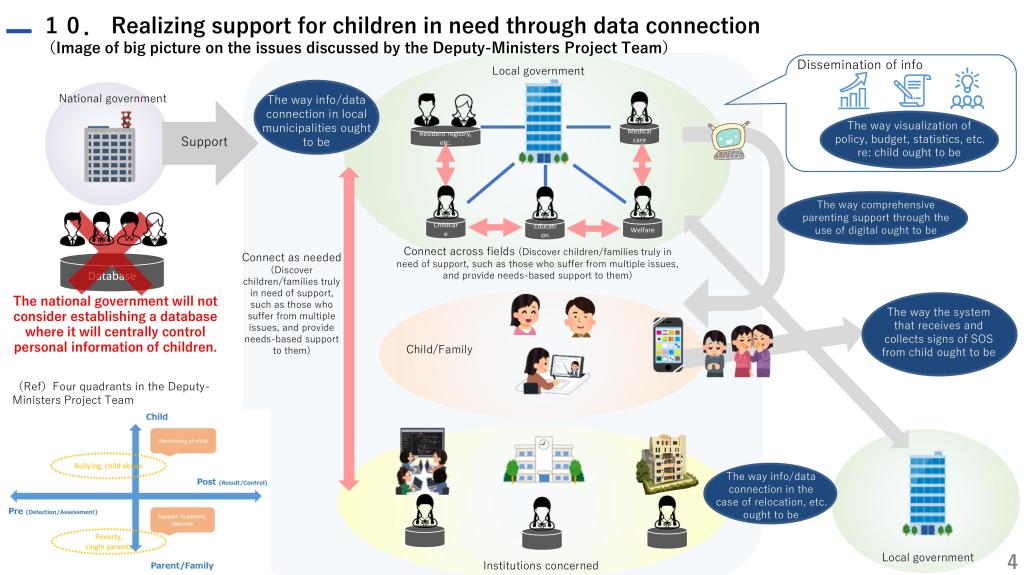

Although most of the policy measures are supposed to be taken by MEXT, DA recently started a pilot project for realizing support for children in need (e.g. poverty, child abuse) through data connection across departments and organizations. As for now, when it comes to data in such fields as education, childcare, child welfare, medical care, etc., they are handled at different departments within the local government. Additionally, there are a variety of institutions concerned such as child consultation centers and schools, each of which, based on their respective role, engage in support for children by utilizing the information that they have. Unfortunately, this sometimes results in each organization/department working in silos without having a clear understanding of which children/families need priority support. For example, the “Child Development Monitoring System” in Minoh City, Osaka Prefecture, classifies children through (1) economic situation, (2) child rearing ability, (3) academic achievement, and (4) non-cognitive abilities, etc.; they then utilize the results for support and monitoring through case meetings, etc.. Building on such practices, we will support local governments by establishing a system for connecting data in education, child welfare, health etc. as needed, utilizing that data to discover children truly in need (e.g. poverty, child abuse) and providing push-type support to them.

IEN: Knowing that fundamentally changing education is such hard work – just like “Tinkering Toward Utopia” – what do you imagine for education in the future?

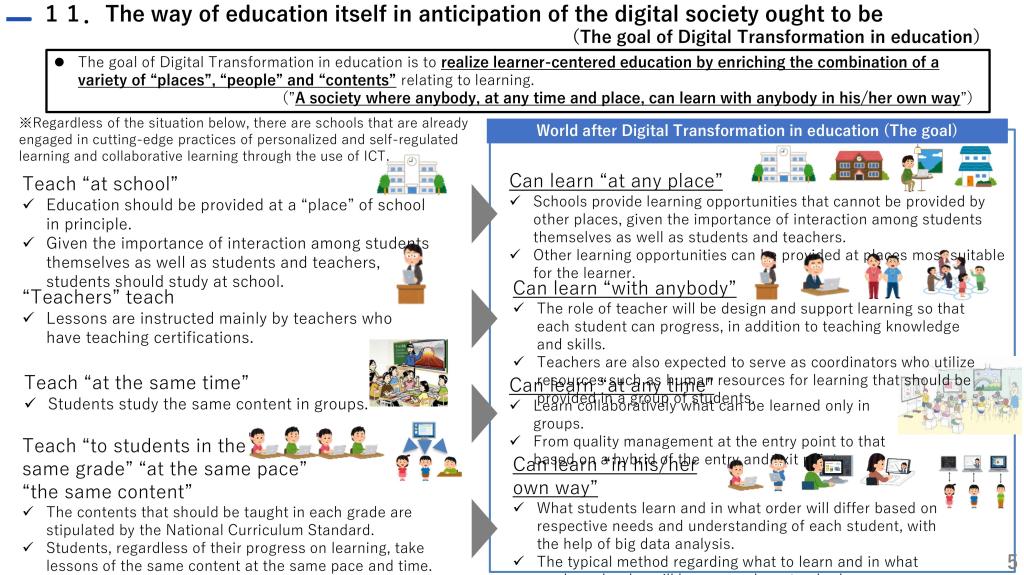

HY: We have to admit the possibility that the fundamental framework of learning instruction in which “in school” “teachers” “at the same time” teach “to students in the same grade” “at the same pace” “the same content” cannot work anymore. This is not because teachers are incapable of doing their jobs. This is because there are so many different needs that children have – from absenteeism, special needs, Japanese-language learners, poverty, to so-called gifted.

With that in mind, we set the goal of digital transformation in education as realizing learner-centered education by enriching the combination of a variety of “places”, “people” and “contents” relating to learning (”A society where anybody, at any time and place, can learn with anybody in his/her own way”). For example, teachers are also expected to serve as coordinators who utilize resources such as human resources for learning that should be provided to a group of students (“Can learn ‘with anybody’”). Additionally, assessment will move from measurement of student learning at the entry point (how much students learn) to that based on a hybrid of the entry and exit points (what attributes and abilities they acquire) (“Can learn “at any time””). Furthermore, what students learn and in what order will differ based on respective needs and understanding of each student, which can be helped with big data analysis (“Can learn “in his/her own way””). This is easier said than done, but MEXT recently set up a new special council composed of stakeholders to discuss concrete policy measures to realize this vision. I’m hopeful that Japanese education will be able to shift from an equality-oriented, lecture-style system to the one that embraces diversity (individually optimized learning and collaborative learning) without undermining our focus on equity.