Can growing concerns about students’ mental health and wellbeing support the emergence of educational practices that combine a focus on academics with more student-centered pedagogies? In the fourth post of this five-part series, Thomas Hatch explores this question, prompted by his conversations with Chinese educators and visits to schools and universities in Beijing, Ningbo, and Dongguan. The first post in this series described the “niches of possibility” within the conventional Chinese curriculum and schedule where innovative schools are developing more student-centered approaches even within a heavily exam-based system. The second post discussed some of the changes in educational policies and regulations that created some flexibility within the system but may have contributed to academic pressures as well. The third post shared some examples of how teachers in a primary school in China are using AI to support students’ learning and engagement. The final post will discuss what can be learned from the ways that the Chinese education system has evolved over the past twenty-five years and how future changes could allow for the emergence of more student-centered instructional practices and more support for students’ wellbeing.

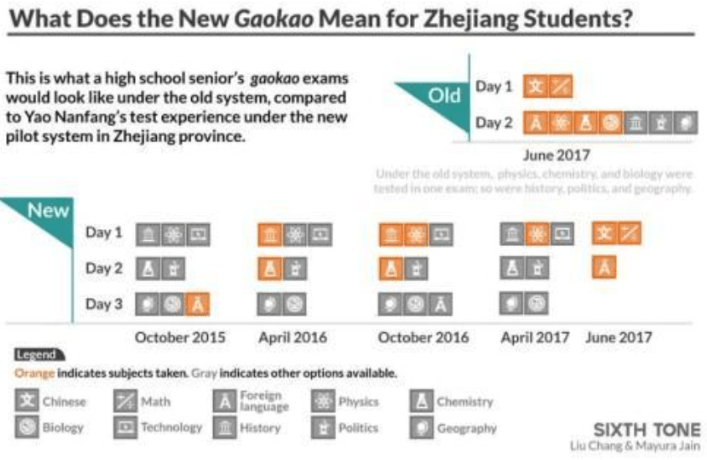

For other posts on education and educational change in China see “Boundless Learning in an Early Childhood Center in Shenzen, China;””Supporting healthy development of rural children in China: The Sunshine Kindergartens of the Beijing Western Sunshine Rural Development Foundation;” The Recent Development of Innovative Schools in China – An Interview with Zhe Zhang (Part 1 & Part 2);” “The Desire for Innovation is Always There: A Conversation with Yong Zhao on the Evolution of the Chinese Education System (Part 1 & Part 2);”“Surprise, Controversy, and the “Double Reduction Policy” in China;””Launching a New School in China: An Interview with Wen Chen from Moonshot Academy;”and ”New Gaokao in Zhejiang China: Carrying on with Challenges

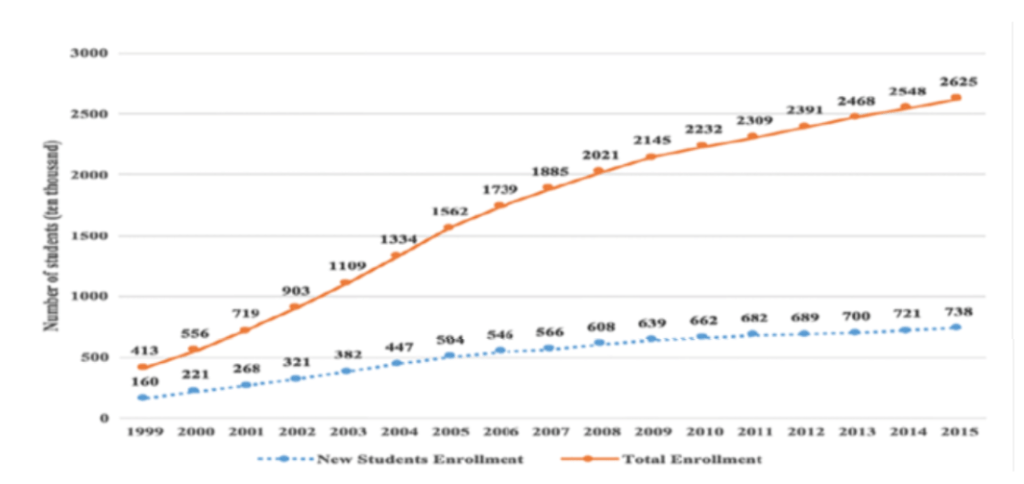

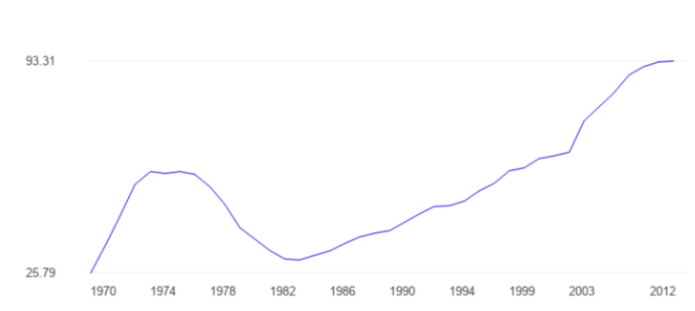

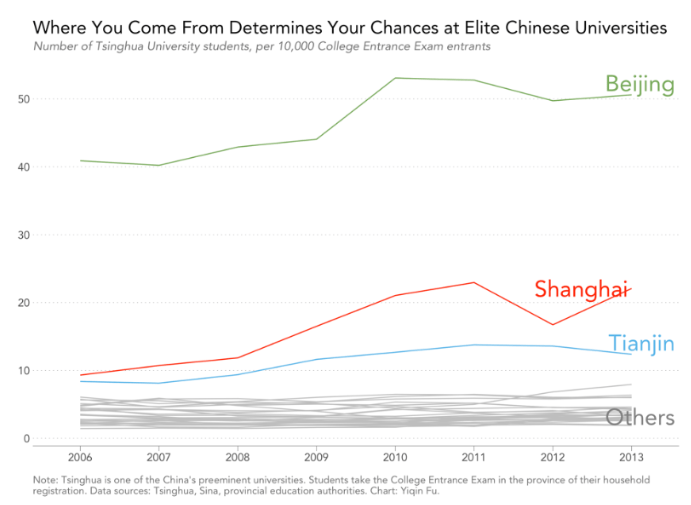

When I arrived in China for the first time in May of 2025, it was already clear that education in China has changed, in numerous ways, both in the last 40 years and just in the last few years as well. As I detailed in the second post in this series, those changes have included the achievement of near universal enrollment through lower secondary school, dramatic increases in the number of students enrolling in college, and new policies and practices governing the Gaokao itself. But I heard over and over again that even with the many changes students today face significantly more academic pressure that previous generations. In the end, I’m left wondering: can the seemingly ever-increasing academic pressure in China increase demands – and opportunities – for developing a balanced education system that supports academic development as well as students’ overall wellbeing?

‘[C]an the seemingly ever-increasing academic pressure in China increase demands – and opportunities – for developing a balanced education system that supports academic development as well as students’ overall wellbeing?

Academic pressure in China has gotten worse: The rise of “neijuan” and “tang ping”

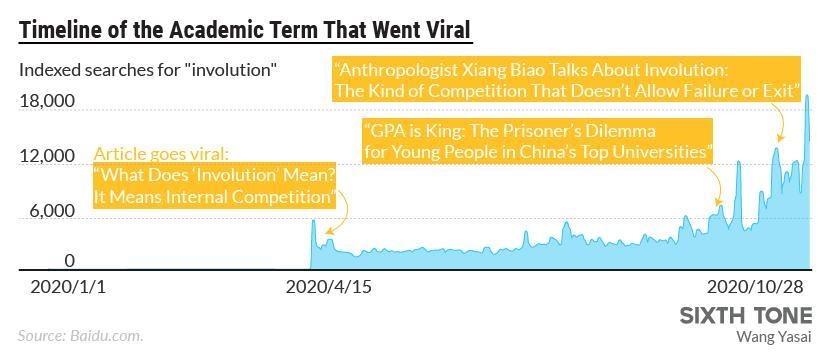

I had only been in China a few days when several colleagues told me about the growth in the use of the terms “juan” and “tang ping.” “Juan,” when used in “Huā Juǎn/花卷” means “roll” as in a steamed bun known as a flower roll. But in recent years “juan” has been used to suggest that a person is being rolled in a washing machine the way we in the West might talk about being caught up “in the rat race,” constantly running like a rat on a spinning wheel. Yi-Ling Liu, writing in the New Yorker in 2021, linked the growth in the use of the term to a video showing a student from one of the top universities in China riding his bicycle and looking at his laptop at the same time.

When I looked up “juan” online, I found a series of stories that explained that the term “nei juan” — represented by the characters for “inside” and “rolling” (内卷) and translated in English as “involution” – emerged as one the most popular Chinese words of 2020. The Chinese anthropologist Xiang Biao describes involution as a process of curling inward that can be considered the opposite of “evolution.” As he puts it, “neijuan” as an “endless cycle of self-flagellation,” in which people are trapped in a competition that everyone knows is meaningless.

For students, it means that getting a high score on the Gaokao is not enough. It means that they also have to compete to get the highest possible grade point average and the most extensive resume. As explained in GPA is king: The prisoner’s dilemma for young people at China’s top universities: “Whether you can learn something or whether it is within your own interests is no longer the only evaluation criteria for engaging in activities. Its value on the resume must be considered. Therefore, this has become a kind of ‘roll’. In order not to fall behind classmates and fall into passivity, everyone has to fill their resumes as much as possible.”

“Whether you can learn something or whether it is within your own interests is no longer the only evaluation criteria for engaging in activities. Its value on the resume must be considered. Therefore, this has become a kind of ‘roll’. In order not to fall behind classmates and fall into passivity, everyone has to fill their resumes as much as possible.”

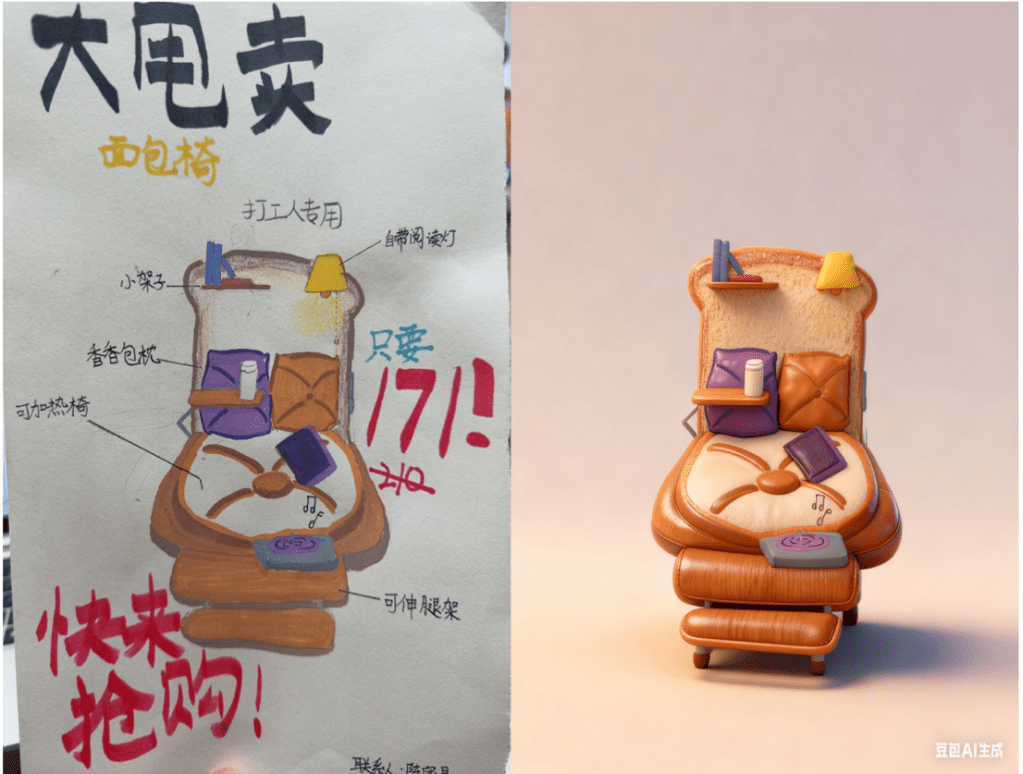

Over roughly the same period, the growth of the usage of “tang ping (躺平),” – translated literally as “lying flat” – represents a response to the pressure and the endless competition. Supposedly, the movement began with a post on a social media site in April of 2021 where the user announced: “Lying flat is my wise movement. Only by lying down can humans become the measure of all things.” Since then, the use of “tang ping” has grown on social media as well, including in a series of posts in 2023 in which college graduates were photographed sprawled out in their commencement regalia.

In “China’s young ‘lie flat’ under social challenges,” Yao-Yuan Yeh explains that the term “describes the generations born in the late 1990s and 2000s who, disappointed by their lack of social mobility and economic stagnation, have decided not to strive for their futures.” One worker who embraced the term was quoted as saying: “According to the mainstream standard, a decent lifestyle must include working hard, trying to get good results on work evaluations, striving to buy a home and a car, and making babies. However, I loaf around on the job whenever I can, refusing to work overtime, not worrying about promotions, and not participating in corporate drama.”

Interpretations of “tang ping” vary, however. Some I spoke to used it to imply that students who checked out of classes or group activities were lazy or entitled and unwilling to do the work required of others. But “tang ping” also refers to those who drop out or disengage more as a form of resistance, a refusal to participate in the “roll” and “rat race” and all that they entail. Perhaps reflecting both interpretations at once, one survey of a nationally representative sample of adults in China found that, in general, “tang-ping related behaviors” were considered morally wrong, but they were considerable acceptable in scenarios where there was a low expectation that effort would be rewarded (such as working in a company that promised to pay performance bonuses but rarely did).

Could growing concerns about student’s mental health and wellbeing create a better balance in Chinese schools?

Taken together, “neijuan” and “tang ping” illustrate an impossible choice for Chinese students – join in the endless competition for academic achievement or drop out and lie flat – without any guarantee that either will lead to a better life. Could this impossible choice propel innovation? Already, these growing pressures have contributed to the double reduction policy and greater attention to mental health.

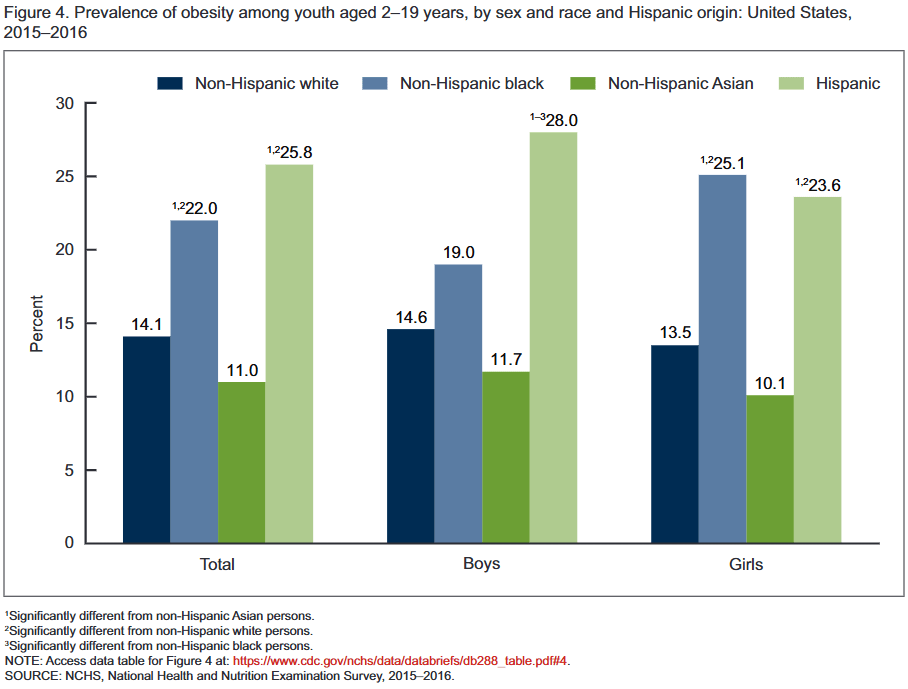

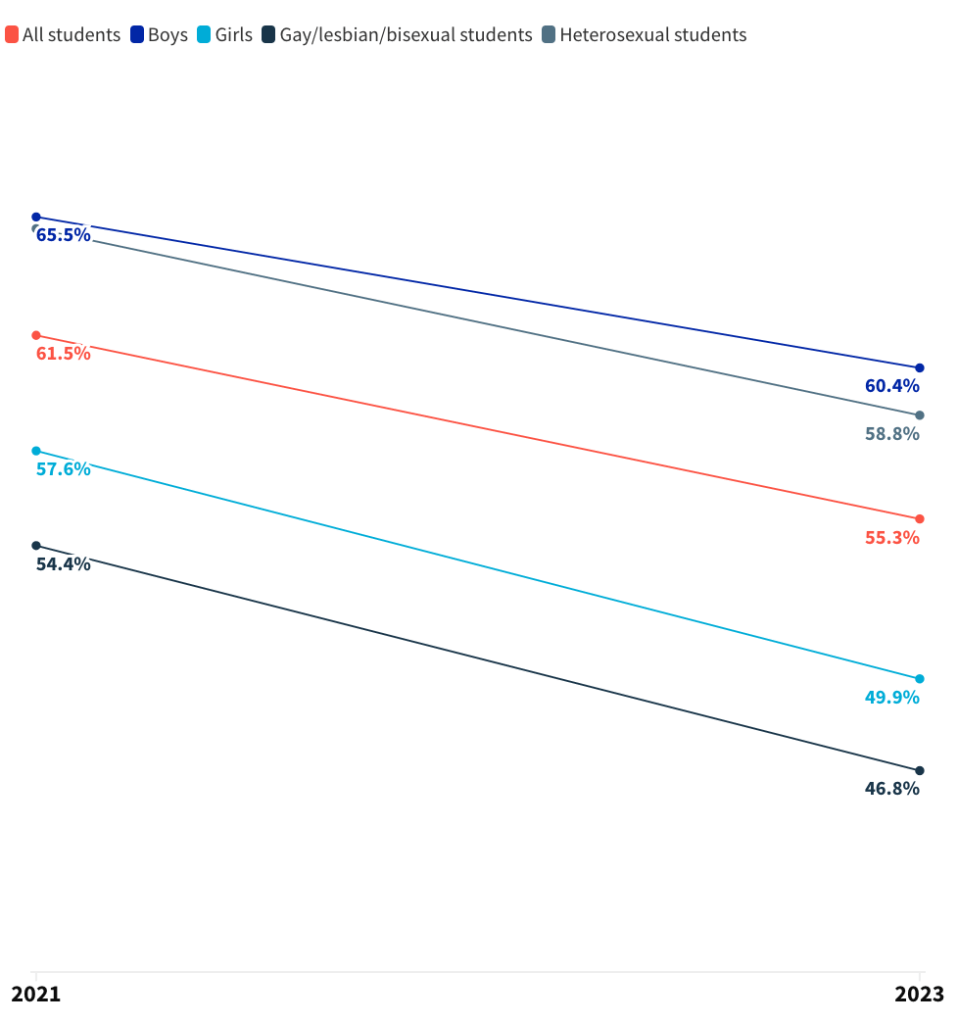

Although many parents in China have been reluctant to recognize or discuss problems of mental health, a widely cited survey from the Chinese Academy of Sciences in 2021 revealed that almost one out of four teenagers report depressive symptoms and a professor at the institute, Chen Zhiyan, said over one hundred studies over the past two decades reveal that mental health has gotten worse. A more recent survey from a Chinese think tank in 2023 also found that 26% of secondary school students said they have depressive symptoms once a week, 15% report symptoms twice a week or more. Media reports have also stated that over 7 million children between 4 and 16 suffer from mental or behavioral conditions and estimated that nearly 100,000 minors died from suicide annually. Anecdotally, clinics also report increased visits and hospitalizations, and an emergency psychological consultation hotline in Shanghai has seen a sharp rise in calls from students as well as parents seeking help for their children.

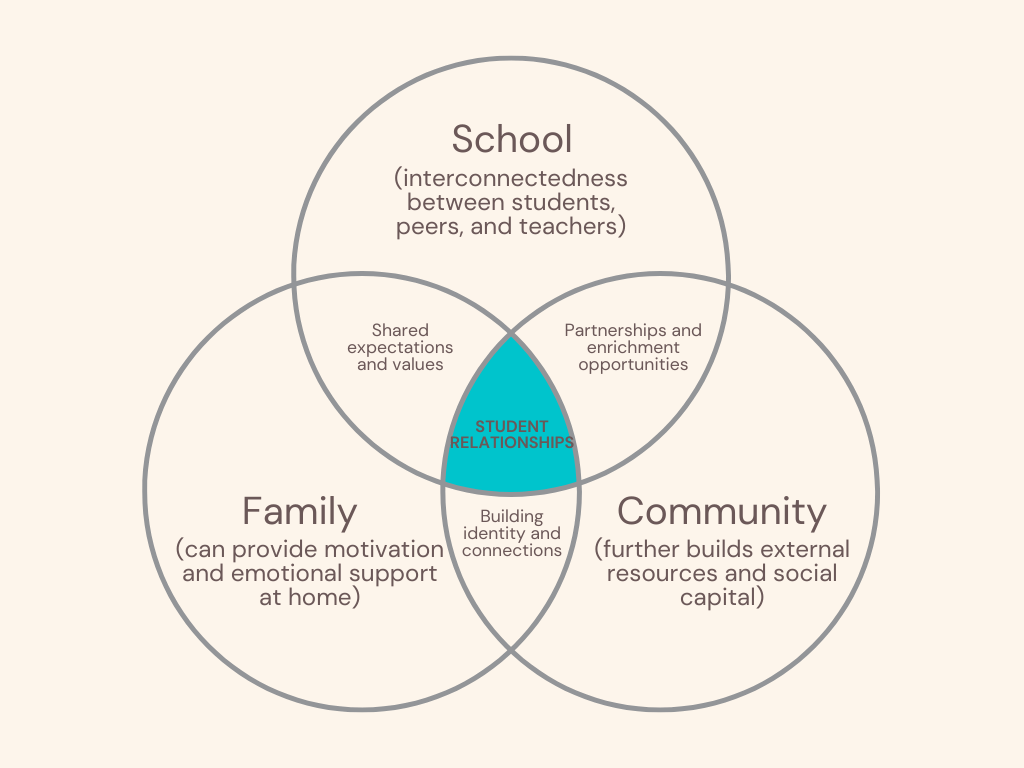

In response, in 2020, the Chinese government introduced “depression assessments” as part of mandatory health screenings for high school students, and in 2021, the Chinese Ministry of Education issued a directive to strengthen professional support and scientific management, and strive to improve students’ mental health literacy.” Following that directive, the education authority in Beijing required primary and middle schools to incorporate mental health education in their curricula and to hire at least one dedicated counselor to address students’ psychological needs. In 2023, China established a National Advisory Committee for Students’ Mental Health to be “responsible for research, consultation, monitoring, evaluation, and scientific popularization of mental health work in universities, middle schools and primary schools across the country.” In addition, an official from the Chinese Ministry of Education declared “The whole of society has reached a consensus to strengthen the mental health education of students,” and the Ministry announced a series of guidelines to safeguard the mental health of young people. Key steps include:

- Primary and secondary schools have to have at least one full-time or part-time teacher on mental health and universities are required to have at least two full-time psychology teachers.

- Primary and secondary schools are encouraged to incorporate psychology courses into their curriculum, and universities are required to have compulsory courses on psychological health.

- Counties need to conduct psychological evaluations at least once a year and establish mental health records for students from the senior levels of primary school and beyond, and universities are also expected to conduct mental health evaluations of all new students.

The guidelines also reiterated key aims of the earlier double reduction policy and declared that “effective measures should be taken” to reduce homework and tutoring and to ensure students have two hours of physical exercise daily. The guidelines also noted that to ensure implementation, “students’ mental health will be taken into account when evaluating the work of provincial governments and administrators of all levels of schools.” As with changes to the Gaokao and the double reduction policies, the question is whether or not the pressure to change continues to grow. Will the desire to support youth mental health and wellbeing continue to spread? Will educators and policymakers take advantage of this window of opportunity and extend and deepen these initial efforts?

Next week – What Conditions Could Foster a More Balanced Education System? Stability & Change in the Education System in China (Part 5)