In part 2 of this two-part post, Sierra Bickford scans recent news and research on education to list some of the innovative approaches schools and communities have developed to make sure all students got the food and nutrients they need during and after the school closures of the COVID-19 pandemic. Part 1 outlined the essential role access to food and nutrition plays in supporting healthy development for students both in the US and around the world. These posts are part of IEN’s ongoing coverage of what is and is not changing in schools and education following the school closures of the pandemic. For more on the series, see “What can change in schools after the pandemic?” For examples of micro-innovations in other areas, see IEN’s coverage of new pathways for access to college and careers and new developments in tutoring: Building Student Relationships Post-Pandemic in School and Beyond; Still Worth It? Scanning the Post-COVID Challenges and Possibilities for Access to Colleges and Careers in the US (Part 1); New Pathways into Higher Education and the Working World? Scanning the Post-COVID Challenges and Possibilities for Access to Colleges and Careers in the US (Part 2); Tutoring takes off and Predictable challenges and possibilities for effective tutoring at scale.

The school closures of the COVID-19 pandemic disconnected children around the world to critical sources of food, including school meals. Fortunately, educators, community members and others have developed a host of new mechanisms, resources, and partnerships to make sure children get access to healthy and healthier meals. These “micro-innovations” include new ways to work with community partners, including farmers, nonprofits, chefs, and local vendors and local ingredients to improve nutrition, strengthen regional economies, and increase student engagement. Other developments include using centralized kitchens and new policies and regulations to increase production and lower barriers to access. A few notable efforts also show how several countries have reworked funding structures to sustainably scale school meal programs. All these initiatives are helping to reduce costs, elevate meal quality, and ensure every child can eat with dignity and ease.

How to Use Community Partners and Local Ingredients

- Zambia: Schools across Zambia are receiving funding from the One Hectare Program to support student run gardens and greenhouses. These gardens help supply school meals and make the community less vulnerable to drought and famine; it functions not only as extra food but also an opportunity to learn. The gardens are taken care of by the students who learn valuable skills such as “drip irrigation, organic sack gardening, and environmental protection.”

- Kenya: In 2024, Kenya launched its national chapter of the school meals coalition and created a meals program that focuses on relying more on regional resources by employing local farmers growing region specific foods such as sorghum, cowpeas and potatoes. This not only increases the nutritional value of school meals but also supports local small business farmers. In collaboration with the Ministry of Health and the World Food Programme, the Ministry of Education is also developing a national menu guide in order to encourage the production of more sustainable and diverse meals.

- France: Legislation has been passed to accelerate the transition to a more sustainable and healthier diet. Regulations put in place since 2021 include requirements for certain percentages of ingredients to be purchased from local and sustainable sources and specify some meal content for school lunch programs. For example, “out of 20 meals, children must be offered no more than four starters with a fat content of 15% or more; at least four fish-based meals (or a dish containing 70% fish or more), and at least 8 whole-fruit desserts.”

- Hawai’i: The State Department of Education created a pilot meals program, the ’Aina Pono Farm to School initiative. Through the pilot program, students at schools such as Mililani High School in Oahu were able to sample various healthy, less processed dishes and give their personal feedback on menu choices. As a result, students ate far more of the meals on offer, reducing food overproduction at the school by 20%.

- Tasmania: Schools in Tasmania are outsourcing at least one day of food preparation to local charity. Loaves and Fishes get produce from local vendors and cook the food either on or off site. These schools are selected through a competitive application process.

- Haiti: Local farmers in Haiti’s Northeast strengthen nutrition and economy by supplying food to school canteens. The World Food Program purchases up to 9,990 tons of local produce to support struggling farmers and supply school meals to approximately 15,000 students across 200 schools with local nutritious food.

- New York City: The “Chefs in the Schools” initiative brings in local professional chefs to create nutritious cost effective menus for schools. The chefs also provide training for staff.

- Canada: Canada’s first national school food program, funded by 1 Billion dollars in federal funds, is rolling out amid rising need, with provinces and local providers striving to expand hot meal offerings despite funding gaps, aging infrastructure and growing demand from families struggling with food costs.

Using Centralized Kitchens:

- France: Centralized kitchens in France prepare 6,000 to 10,000 servings a day of high-quality food following strict food safety protocols. This cuts down on cost and increases quality.

- Hawai’i: The Hawaiʻi’s Farm to School Action Plan connects schools with local farms to provide fresh, nutritious meals, support farmers, and promote sustainable food systems through a regional kitchen model and community collaboration.

- Sweden: A pilot program transforming school canteens with student-designed spaces, surplus-produce energy bars, and sustainability initiatives has boosted engagement and healthy eating while highlighting the need for long-term investment and multi-agency collaboration to sustain its success.

Lowering barriers to food

- Africa: Food4Education (F4E) is transforming school feeding in Africa through a sustainable, locally sourced model that provides nutritious, affordable meals while supporting local farmers and communities. By 2030, they aim to feed 1 million Kenyan children daily and help other African governments feed 2 million more, creating a scalable blueprint to end classroom hunger across the continent.

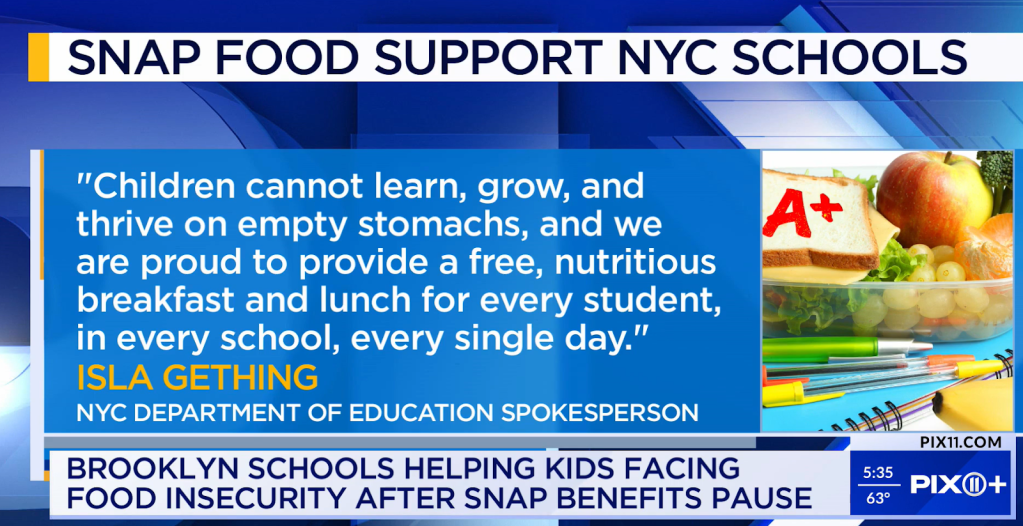

- New York City: In response to rising concerns about federal budget cuts to SNAP, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, a school in Brooklyn has partnered closely with the community organization El Puente and other stakeholders to support their students.

- Colorado: All Colorado public school students will continue to have access to free school meals after voters approved two state referendums on November 5th, 2025, one of which — Proposition MM — will raise state income taxes for those earning an annual income of $300,000 or more.

- United States: A streamlined certification structure has been implemented for a summer food assistance program launched last year. In the first year, some families missed out on Summer food benefits because of confusing enrollment, limited outreach, and short deadlines, despite the program proving highly effective for those who received it. To address the problem, more families will be enrolled automatically, if they are on certain public benefit programs, including free and reduced price school lunch.

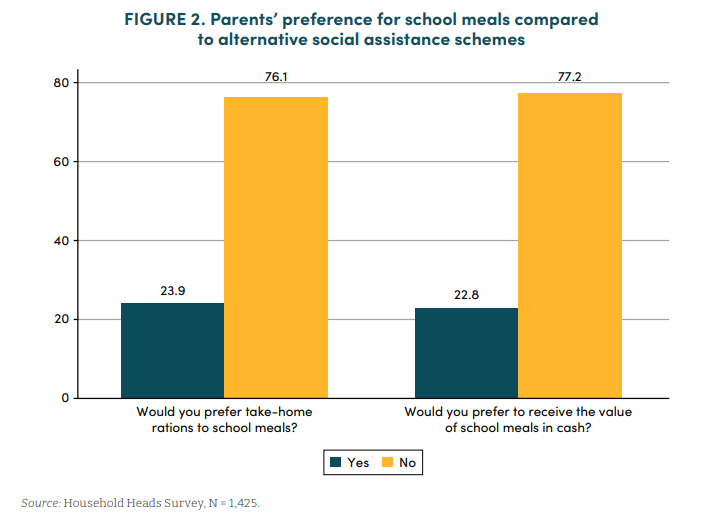

- Ghana: The Ghana School Feeding Programme has found most Ghanaian caregivers prefer on-site school meals over cash or take-home rations, with their choices shaped by program satisfaction, time constraints, and local food prices, suggesting school feeding programs could be more effective by tailoring modalities to regional and household needs.

- United States: Starting in the 2027–28 school year, the USDA will ban online processing “junk fees” for students eligible for free or reduced-price school meals, aiming to expand the policy in the future to ensure all children can access healthy school meals without extra charges.

- California: Schools are offering food trucks to boost lunch participation. Called the Cruisin’ Cafe, the food truck gets more seventh- and eighth-grade students to eat lunch during school. Students won’t have to pay anything for their meals or walk across campus to get lunch at the cafeteria.

- New York City: New York City is investing $150 million to expand modern, café-style cafeteria upgrades to more schools after seeing that redesigned dining spaces boosted student participation in school meals and helped reduce stigma amid rising child food insecurity.

- United States: Districts are using the federal Community Eligibility Provision to offer free school meals by strategically clustering schools to maximize reimbursement, clearly communicating and reassessing eligibility data each year, and boosting revenue through expanded breakfast programs like breakfast-in-the-classroom or breakfast-after-the-bell.

Changing Financing Systems

- Bolivia: Since 2000, the government in Bolivia has supported what has come to be called the Complementary School Meals Program. By 2019, with investments of more than 100 million US dollars, the program provides school meals to more than 2.2 million students – almost 80% of all school-age children and youth. To fund the program, the government has turned to taxing natural resources, specifically hydro carbons, program.

- Mozambique: In Mozambique, $40 million in debt service payments were channeled to school meals by using debt swaps and broader debt relief strategies to redirect repayments toward national education and nutrition priorities.