In this our second post on educational issues in China, Shengyuan Lu, who just received the Master’s Degree at Teachers College in International Educational Development Program, provides an overview of a few of the most prominent sources of information that those in China turn to for information on and discussions of education policies and public opinion on education in China. These include official government and news sources as well more popular social media platforms (in Chinese unless otherwise noted). Links are also provided to some of the educational issues and topics in the news recently.

Xinhua Net – Education

http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/list/cultureedu-education.htm

Xinhua News Agency is the Chinese national news agency, and Xinhua Net is the official website. The education section of Xinhua Net English edition features reports about national educational policies and trials, as most subjects of the articles start with “China.”

Sample Article: China to review mobile apps for students

China Education Daily

China Education Daily is supervised by the Ministry of Education in China. It is the only national-level education newspaper and one of the most influential education media. Here, you will find first-hand announcements of official policies of Chinese education. It is a site for, among other readers, education administrative leaders, school principals and teachers both from public schools and private education organizations.

Sample Article:

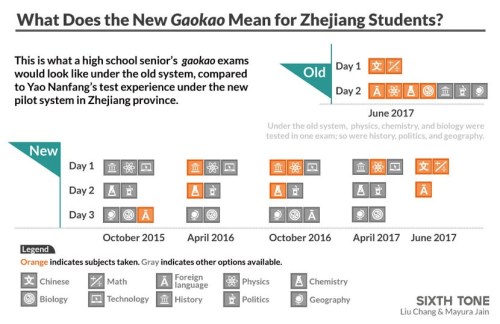

Sixth Tone – Education

http://www.sixthtone.com/topics/10138//education

This is an English website featuring news about China. It is based in Shanghai, belongs to Shanghai United Media Group, and shares the office with The Paper, one of the most influential news websites in China. In the education section of the Sixth Tone, it covers a wide range of topics, including migrant children, college entrance, school safety, education quality, and more.

Sample Article: Why More Chinese Parents Are Timing Their Due Dates for the Fall

Jiemodui

Jiemodui is a website focusing exclusively on education. It focuses on the development of the education industry and reports rising educational products and companies. It also offers analyses of the education policy and market. It is claimed to be the top education-focused website in China. Its readers consist of people in educational companies, investors dedicated to education, and other users including principals, teachers, NGOs, and education media.

Sample Article: Education tutoring companies escape Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou

Sogou WeChat Search

This is the only search engine that can search the personal blog posts published on WeChat. WeChat is the most used chat/social app in China. You may think it as Messenger where you can receive individual chatting messages and information feeds from different bloggers. Because most of the personal blogs are published within WeChat, it is only possible to search and read the articles within the app or specific search engine. Although this search engine is not built only for education articles, most websites, corporations, and individual bloggers have their own accounts on WeChat to publish articles. All the websites listed in this article have their own WeChat accounts. The handle for Chinese MOE Information Office is jybxwb.