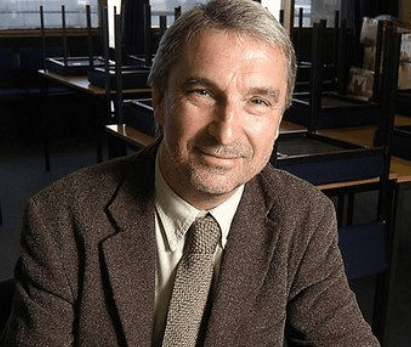

In this month’s Lead the Change (LtC) interview, Stephen MacGregor draws from his experience researching knowledge mobilization as a mechanism for educational change, with an emphasis

on leadership practices within increasingly complex education systems. MacGregor is an Assistant Professor and Director of Experiential Learning at the University of Calgary’s Werklund School of Education. His research focuses on three interrelated strands of inquiry: (1) mapping relational networks between universities and K–12 schools, (2) exploring positive leadership in nurturing professional capital and community, and (3) co-producing knowledge to bridge education theory and practice. The LtC series is produced by Elizabeth Zumpe and colleagues from the Educational Change Special Interest Group of the American Educational Research Association. This year, the Ed Change SIG recognized MacGregor’s work with one of two Emerging Scholar Awards. A PDF of the fully formatted interview will be available on the LtC website.

Lead the Change (LtC): The 2026 AERA Annual Meeting theme is “Unforgetting Histories and Imagining Futures: Constructing a New Vision for Educational Research.” This theme calls us to consider how to leverage our diverse knowledge and experiences to engage in futuring for education and education research, involving looking back to remember our histories so that we can look forward to imagine better futures. What steps are you taking, or do you plan to take, to heed this call?

Stephen MacGregor: I see the call to “unforget” as an imperative to intentionally surface the institutional, policy, and community narratives that have shaped current possibilities for teaching, learning, and leadership. Much of my research and leadership has been motivated by this orientation, particularly in projects that examine how educational systems respond to and often resist new ideas, and how practitioners navigate the attendant dynamics.

“I aim to counteract tendencies to erase dissenting voices or inconvenient histories.”

One step I am taking is to more deliberately position historical analysis alongside contemporary policy and practice studies in my research (e.g., MacGregor & Friesen, 2025; MacGregor et al., 2022, 2024). In my recent and ongoing research into multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) and social-emotional learning implementation in Alberta schools, for example, my colleagues and I examine the present-day enactment of new initiatives as well as trace how prior reform cycles, funding shifts, and governance structures have left their imprint on current efforts. The historical grounding deepens our understanding of why certain approaches gain traction, why others fade, and what legacies of inequity persist beneath what can often be surface-level change.

Equally, my scholarship on knowledge mobilization in educational leadership has highlighted how selective memory (i.e., what is remembered, forgotten, or deemed irrelevant) shapes the evidence that informs decision-making. Through collaborative work with system leaders to design processes that make research use more transparent and inclusive, I aim to counteract tendencies to erase dissenting voices or inconvenient histories (e.g., experiences with failure and what can be learned from them). This has included creating tools and frameworks that explicitly prompt leaders to consider historical precedents and the perspectives of communities that have long envisioned and pursued their own futures for education, often outside formal institutional channels.

In my role as Director of Experiential Learning at the Werklund School of Education (University of Calgary), I am working to integrate a longer-term, historically grounded perspective into the design of learning experiences for undergraduate and graduate students. This means helping future and current practitioners see educational challenges as part of longer trajectories shaped by policy and shifting social priorities. To that end, I am building local and international partnerships that connect our students with varied educational histories and contexts (e.g., multiple international teaching placements through the Teaching Across Borders program). This work also involves embedding reflective and archival practices into experiential learning. I ask participants in our initiatives to document their experiences in ways that attend to historical influences (e.g., speaking with practitioners about prior reform efforts, exploring changes in governance or community engagement over time). My aim is for these experiences to leave participants better prepared to design and lead educational opportunities that are responsive to both the past they inherit and the future they help shape.

Looking ahead, I plan to expand my research on how system leaders and policymakers draw on history, explicitly or implicitly, when justifying decisions and setting priorities. I am especially interested in how prevailing narratives within leadership discourse and policy texts shape which forms of evidence are privileged and which innovations are recognized. Moreover, I aim to support leadership practices and research use that are historically informed and attentive to marginalized perspectives.

LtC: What are some key lessons that practitioners and scholars might take from your work to foster better educational systems for all students?

SM: A consistent lesson from my research is that fostering better school systems for all students requires a shift from viewing change as a series of isolated initiatives to understanding it as an

iterative, relational process. Educational change is seldom straightforward; it unfolds amid fluctuating policy landscapes, evolving priorities, and the complexities of daily practice. When leaders and practitioners treat each initiative as if it exists in a vacuum and without regard for prior efforts, contextual constraints, or the cumulative impact on educators and learners, they risk repeating past missteps and missing opportunities to build on existing strengths.

From my MTSS research, another lesson is that systems must attend to implementation drivers (Fixsen et al., 2015) as the key organizational and human supports that make new practices possible in schools and thus that enable change efforts to take root and grow. These include competency drivers such as targeted professional learning and coaching; organization drivers such as supportive policies, data systems, and resource alignment; and leadership drivers that guide decision making in response to challenges. Where these drivers are deliberately cultivated in concert, educators are better positioned to adapt initiatives for their own contexts and ensure they serve the needs of their students.

Another lesson relates to the role of failure in system improvement. Too often, unsuccessful reforms are quietly set aside without deliberate reflection, resulting in the same pitfalls being encountered repeatedly. My research points to the value of structured learning from failure, which means creating processes that allow for analysis of what went wrong or failed to produce the intended outcomes, identifying underlying mechanisms, and generating insights for future action (MacGregor & Friesen, 2025). This reframing of failure as a legitimate and even necessary part of improvement strengthens adaptive capacity. It also shifts organizational culture toward openness, candour, and a willingness to iterate rather than abandon promising work prematurely.

Finally, across my work in schools, international partnerships, and higher education settings, I have seen that strong, trust-based relationships are essential for the two previous lessons to function at their best. Competency, organization, and leadership drivers all depend on the mutual respect and shared ownership that develop when schools and broader systems engage as genuine partners. Moreover, relationships provide the foundation for honest conversations that allow people to name challenges directly and work together on responses that matter.

For practitioners, these lessons might spark reflection on ways to anchor new initiatives in an understanding of local context and history, strengthen the drivers that support implementation, build habits of learning from setbacks, and invest in relationships as a foundation for change. For scholars, they might prompt thinking about how to design research that examines the drivers of educational change in action and supports their development, which could offer knowledge that is attentive to the realities and contexts where change is being pursued.

LtC: What do you see the field of Educational Change heading, and where do you find hope for this field for the future?

SM: I see the field of educational change continuing to wrestle with complexity while becoming more deliberate in how it integrates various forms of knowledge and expertise. There is a growing recognition that meaningful change depends on aligning policy, practice, and community engagement in ways that are contextually grounded and historically informed. I am hopeful for continued attention to strengthening the foundational conditions (e.g., coherent governance structures, stable funding streams, and collaborative professional learning) that allow promising approaches to take root and adapt over time.

I also anticipate deeper commitments to equity-informed leadership, with systems increasingly

recognizing that meaningful change cannot happen without addressing the structural inequities that shape educational experiences. Among many approaches, this could involve more substantive power sharing with communities, particularly those whose knowledge has historically been overlooked or marginalized. It could also involve embedding processes for shared decision-making and transparency into the everyday work of schools and systems.

What gives me hope is the growing body of scholarship and practice that treats relationships as the core infrastructure of educational change. I see this in system leaders who intentionally create spaces for dialogue that can bridge ideological divides, in educators who invite students and families into co-design processes, in cross-sector partnerships that build locally relevant solutions, and in research-practice networks that enable long-term collaboration across institutions and jurisdictions (e.g., Hubers, 2020; Rechsteiner et al., 2024; van den Boom Muilenburg et al., 2022). I am also encouraged by how scholars and practitioners are integrating multiple ways of knowing and thus valuing both rigorous research and the lived experience of educators, students, and communities. I am hopeful that we are moving beyond asking “what works?” by appending that question with “for whom, under what conditions, and with what consequences?”(Boaz et al., 2019).

References

Boaz, A., Davies, H., Fraser, A., & Nutley, S. (Eds.). (2019). What works now? Evidence-in- formed policy and practice. Policy Press.

Fixsen, D., Blase, K., Naoom, S., & Duda, M. (2015). Implementation drivers: Assessing best practices. National Implementation Science Network.

Hubers, M. D. (2020). Paving the way for sustainable educational change: Reconceptualizing what it means to make educational changes that last. Teaching and Teacher Education, 93.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103083.

Rechsteiner, B., Kyndt, E., Compagnoni, M., Wullschleger, A., & Maag Merki, K. (2024). Bridging gaps: A systematic literature review of brokerage in educational change. Journal of Educational Change, 25(2), 305–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-023-09493-7.

van den Boom-Muilenburg, S. N., Poortman, C. L., Daly, A. J., Schildkamp, K., de Vries, S., Rodway, J., & van Veen, K. (2022). Key actors leading knowledge brokerage for sustainable school improvement with PLCs: Who brokers what? Teaching and Teacher Education, 110.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2021.103577.

MacGregor, S., & Friesen, S. (2025). Reframing failure: Lessons from educational leaders

facilitating multi-tiered systems of support. Journal of Professional Capital and Community. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-09-2024-0168.

MacGregor, S., Friesen, S., Turner, J., Domene, J. F., McMorris, C., Allan, S., Mesner, B., &

Sumara, D. (2024). The side effects of universal school-based mental health supports: An integrative review. Review of Research in Education, 48, 28–57.