In the second part of this two-part interview, Melanie Ehren talks with Thomas Hatch about the five “waves of funding” designed to help the Dutch education system respond to the learning challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic and related school closures. The first part of this interview focused on the initial school closures and the suspension of exams in the Netherlands. Ehren is Professor and Director of Research of LEARN! at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. This interview is one in a series exploring what can change in schools after the pandemic? Previous interviews and posts have looked at developments in Italy, Poland, Finland, New Zealand, South Africa, and Vietnam. Other blog posts from Melanie Ehren include A view from the Netherlands: Melanie Ehren on school closures and the pandemic; Lead the Change Interview with Melanie Ehren; A call to action in the Netherlands: Addressing rising inequality in a decentralized system.

Thomas Hatch (TH): You and your colleagues spent a considerable amount of time studying how the Dutch government has used a series of funding initiatives to help schools and students in the Netherlands recover from the pandemic. Can you give a sense of these “waves” of funding and how schools and school networks used them?

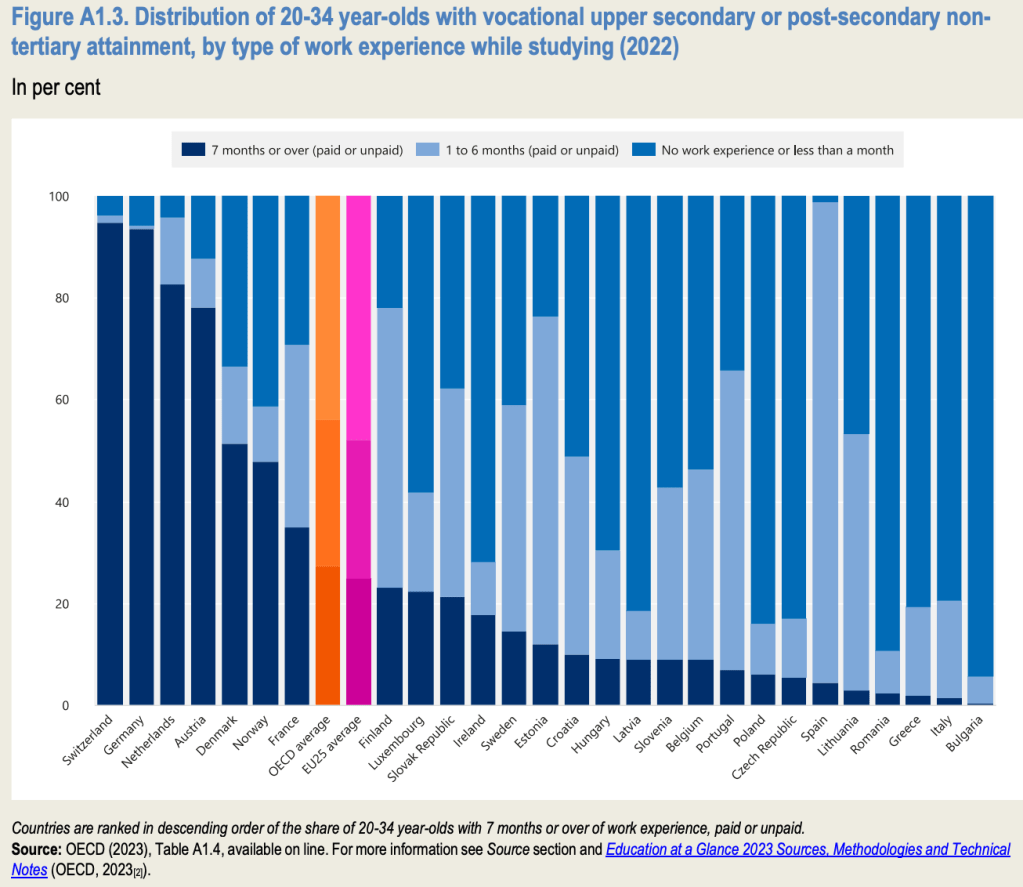

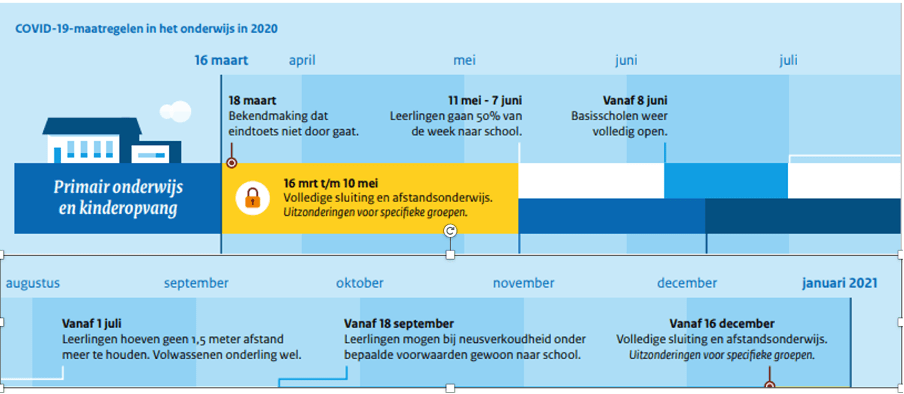

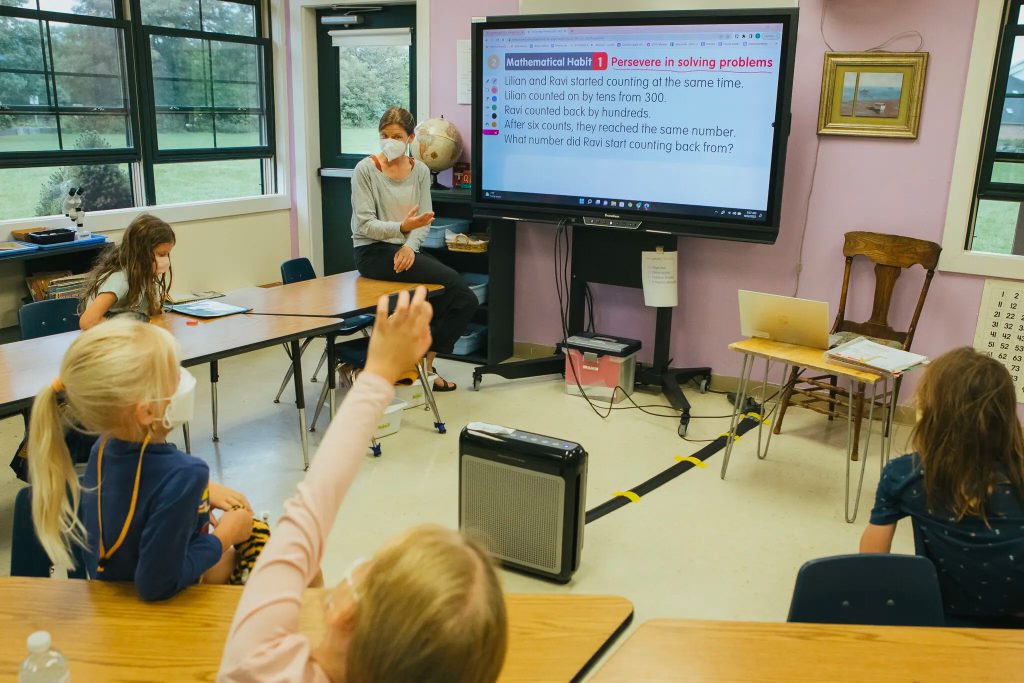

Melanie Ehren (ME): The Dutch government provided funding to help schools respond to COVID pandemic in five different “waves,” with the first wave in July, 2020, after the initial school closures. At first, consistent with the decentralized Dutch system, schools and local school boards could decide on the type of “catch-up” approach to pursue and which pupils were eligible for the additional support. However, after the first round of funding there was considerable negative press about the unfocused nature of the approaches and the fact that some of them had little, if anything, to do with instruction. For example, in one meeting, I heard some people complaining about a school that used the funds to take their students on a trip to an amusement park (like Disney-land), with the rationale that children had experienced such socio-emotional suffering that they needed a break and a chance to re-establish their relationships with peers and their teachers.

After the initial round, the requirements for the funding were tightened and schools had to use student achievement results to target students with “learning loss” and to choose from a ‘menu of effective interventions’ to help them catch-up. This menu was modelled directly on a “Toolkit” developed in England to ensure that schools used “catch up” approaches that had some “evidence of effectiveness.” The first version of this was what the Dutch called a “menu card,” which was essentially the English toolkit translated into Dutch.

The “Toolkit” created by the Education Endowment Foundation used in England and the Dutch version based on the English model

I think this move was made because the government felt that schools were not very evidence informed in their thinking about what interventions and programs to implement in the first wave. In fact, when we interviewed schools that had applied for funding about why they picked a particular intervention – asking things like “why are you thinking that this program might lead to improved outcomes for this particular groups?” – many of them had a hard time answering. In some cases, the decisions appeared to be based on professional expertise and their previous experiences of what had worked or didn’t work well for their students. But some schools also told us they were choosing these programs out of convenience or building on partnerships with external agencies that were already in place. For example, they might say “this is a tutoring agency we’ve worked with before; we’ve had good results with them, so we thought that that might be a good way to use the funding” or “this is something that we know we can organize for our school.”

For this second wave of funding, we studied the applications of schools and found that the schools planned to focus mainly on three types of outcomes:

- School performance (primary education: language and arithmetic; secondary education: core subjects)

- Well-being/social-emotional development of pupils

- Learning skills

Despite these plans, we found that many schools actually ended up using the funding quite differently. For example, a school might have planned to spend the funds on after school tutoring; on providing additional remedial instruction at the start of the school day; or on having additional teachers in the classroom. But then when it came time for implementation, another issue or need might have emerged or they might have found they couldn’t secure additional teachers. Overall, schools were really struggling to organize these programs as planned because of the constant disruptions to in-person teaching and then there was a second lockdown so they were constantly changing and revising. I also had many conversations with school leaders who said “we did not apply for this funding, because we need more time to actually think about what makes sense for our kids.” We detailed some of this at the time in a blog post “Catch-up and support programmes in primary and secondary education.”

Overall, schools were really struggling to organize these programs as planned because of the constant disruptions to in-person teaching and then there was a second lockdown so they were constantly changing and revising.

Over time, the government did add more background information and context to the menu to help schools to use the information to make choices. For example, the new version produced by the Ministry of Education, Culture & Science (which they referred to as an “Intervention card improving basic skills“) included links to guidance and support for choosing and using the guidance and urged the schools to consider the demands of their own context, stating: “it is important how your school implements a chosen intervention. For a concrete step-by-step plan, you place each approach in the context of your school: does this approach suit the education you provide, your students and the issues you face? The professionalism and autonomy of the teacher are paramount here.” All of this has led to much more emphasis on evidence-based and evidence-informed work in schools, and particularly how the government can support that. That’s another consequence of the pandemic in the Netherlands, I think: A belief that we need to build more capacity in schools for using research evidence to improve education.

TH: What’s happening now and what’s likely to happen in the future?

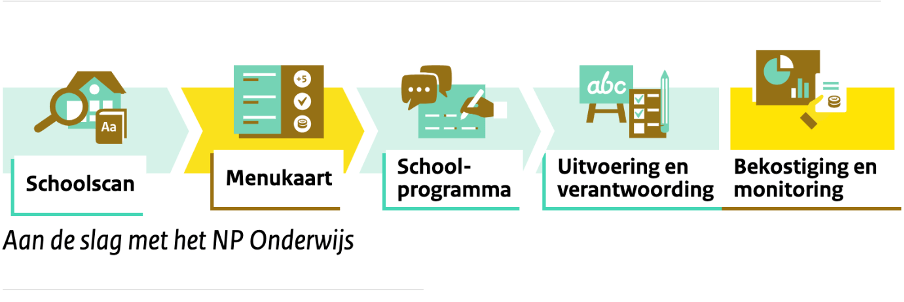

ME: Building on the catch-up schemes, the national government has developed a broader funding scheme – the National Program for Education – that is continuing to help schools, particularly schools with a high level of deprivation, to improve reading, writing, and literacy. This program provides an additional investment of 8.5 billion for 2.5 years for the entire education system. This National Program offers funding to improve education in these basic areas, and schools are expected to use the same approach as under the catch-up funding: the schools have to identify children who need additional support and use the menu card to decide on what kind of interventions are effective. But the national program of education has a much wider infrastructure to improve basic skills, including support teams that are initiated by the Ministry of Education to work with schools, but all around this idea of evidence-informed interventions.

“Get started with the NP Education” [translated] a graphic depicting how Dutch schools should select, implement and monitor “catch-up” programs.

Despite the huge amount of funding there have been a lot of critiques of the national government, given the short time span in which the money has to be spent, which doesn’t allow schools to implement more sustainable solutions to improve education and learning outcomes. The funding for example doesn’t allow schools to hire additional staff as these would have to be offered permanent employment which cannot be guaranteed with temporary funding.

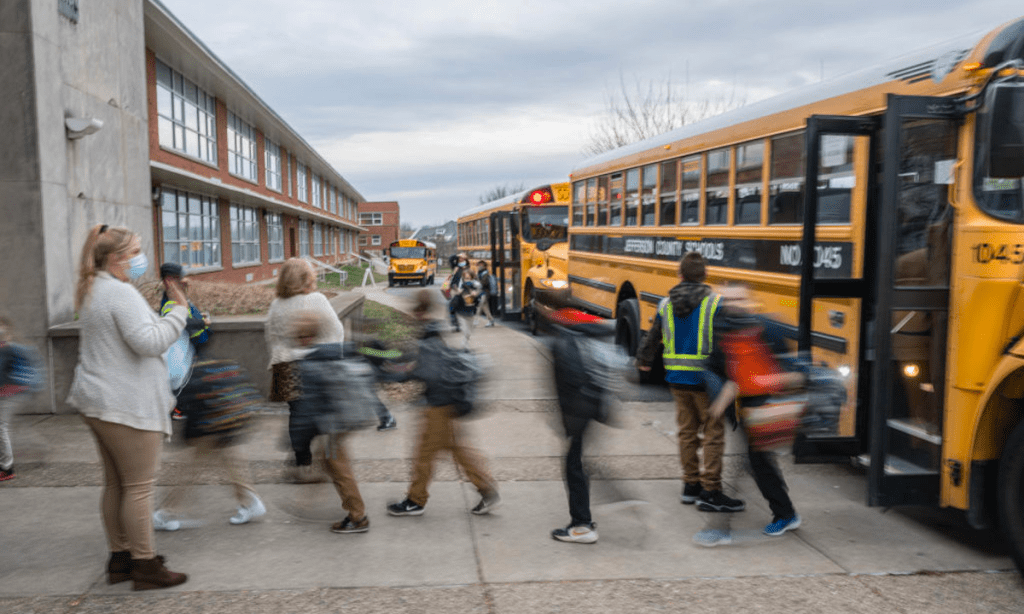

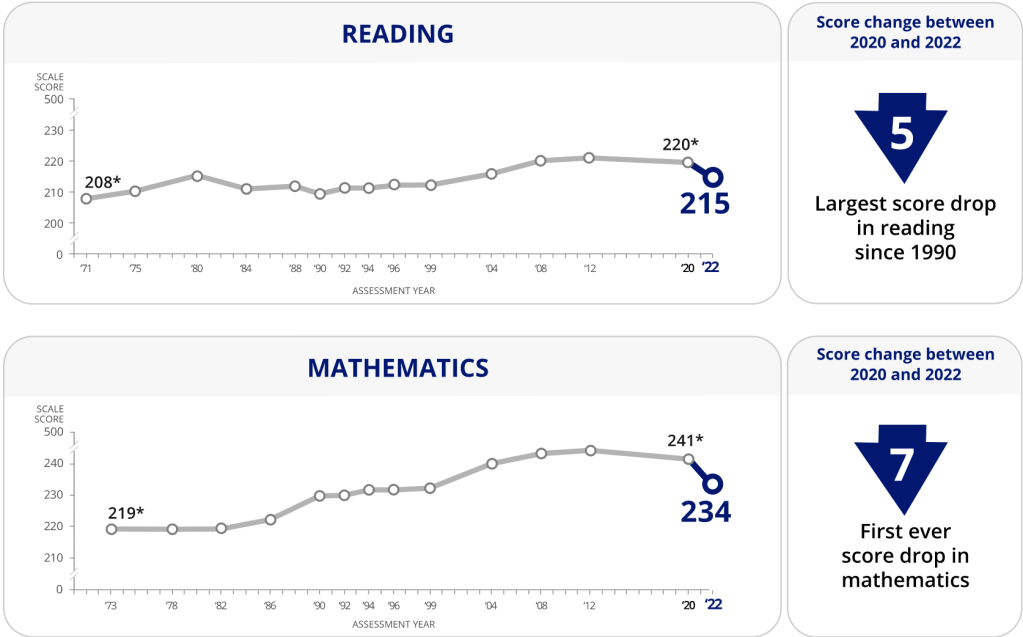

Given that the most pressing problems in our education system are teacher shortages, high inequality and a decline in student outcomes in literacy and numeracy, there is an understanding that a long-term investment and program of reform is required to improve education. The short-term catch-up programs seem to have done relatively well in getting students back on track, but they have not been able to buck the wider trends in declining outcomes and increasing shortages of teachers.

In some ways, all of this a natural consequence of problems coming out of the school closures, but it’s reinforced by the fact that the Netherlands’ performance has been declining in international surveys like PISA at the same time that inequality has been increasing. That’s also something that the Dutch Inspector of Education has reported on in their annual reports. All of these reports have been alerting people to the facts that children are not reading at home and that reading scores are declining, and that’s having an effect on other outcomes. All of these things come together in the drive towards trying to improve basic skills.

TH: Can you talk a little about how the response in NL compares to those in other systems you’re familiar with, particularly the UK?

ME: During the pandemic, the Netherlands had a decentralized approach to allow schools to choose a contextually appropriate response to school closures within a centralized funding framework. This is different from other countries such as the UK that saw a highly centralized roll-out of a tutoring programme. Now, however, we are seeing a much more centralized approach to improving education. Recently an ‘interdepartmental investigation into education (IBO Koersen op kwaliteit en kansengelijkheid) was published with a range of proposals for stronger governmental coordination/control over education to reduce inequality and enhance learning outcomes, including more centralized coordination of the curriculum, compulsory assessments, more inspection, enhancing evidence-informed work in schools (including through an application for funding to hire a school support team to work with a school). Given the Netherlands’ tradition of high autonomy and freedom of education, this is being described as ‘a committed and responsible government’, but it is essentially a move towards greater centralized control.

Now, however, we are seeing a much more centralized approach to improving education... Given the Netherlands’ tradition of high autonomy and freedom of education, this is being described as ‘a committed and responsible government.’

TH: Have you seen any particularly innovative or promising new practices or policies that have grown out of the COVID response?

ME: Schools are much better equipped to move to online learning when needed. With the train strikes we had in some regions last year, schools closed again but they have been able to take advantage of the new infrastructure and teachers’ skills to teach online. In Higher Education there is some discussion of having a COVID-generation of students (who also talk about themselves in these words) who sometimes find it difficult to engage in on-campus education and feel they should have more support.

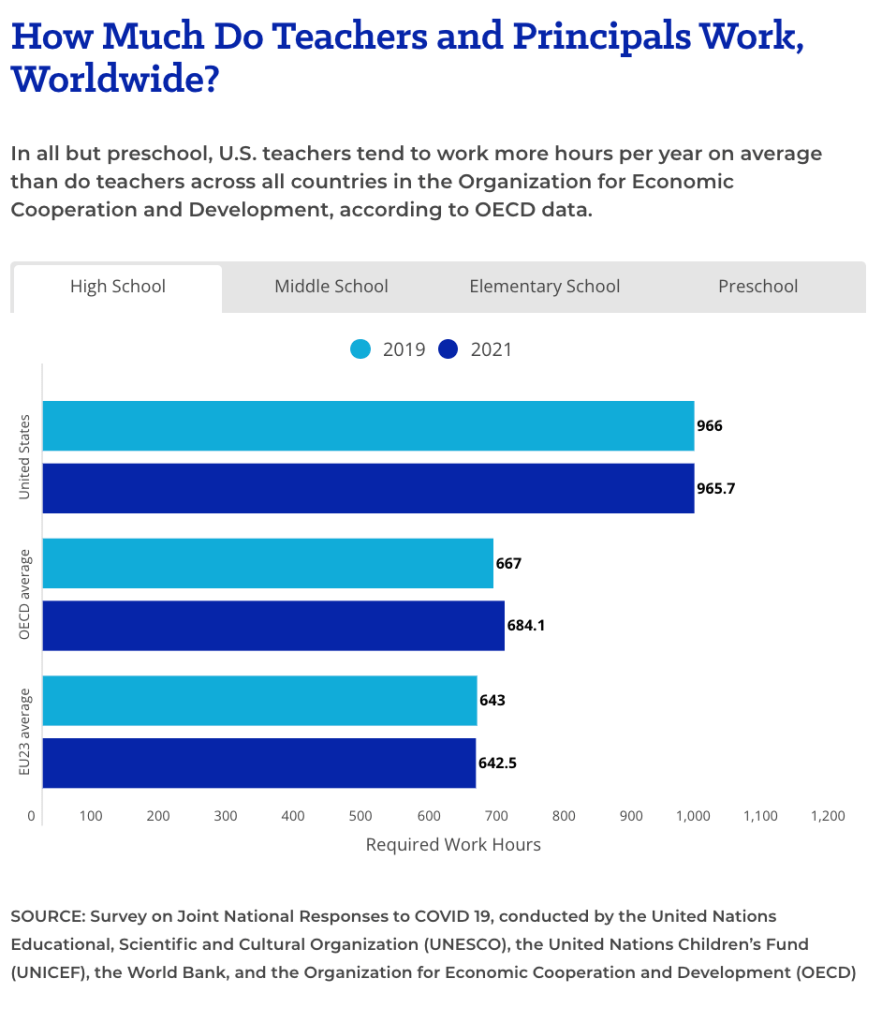

Teacher shortages are also increasing and this is partially attributed to the high levels of stress and workload during the pandemic and reduction of the status of teachers in society and the cost of living in relation to teachers’ salaries. Our most recent research also suggests that there may be an increase in the number of teachers working on private contracts (through recruitment agencies). The amount of temporary funding for catch-up programmes and the National Education Program may also lead to an increase in private agencies and what some are calling “edubusinesses,” but I have not yet seen the evidence on this.

Related Resources & Articles:

Subsidie en basisteams voor scholen om basisvaardigheden te verbeteren [English: Subsidies and basic teams for schools to improve basic skills], Rijksoverheid

Eerste inzichten over inhaalprogramma`s in het po en vo [English: Catch-up and support programmes in primary and secondary education], LEARN!

Informatie voor onderwijsprofessionals [English: Information for Professionals], LEARN!

Rapport De Staat van het Onderwijs 2021 [English: Report on The State of Education 2021], Inspectie van het Onderwijs

Rapport De Staat van het Onderwijs 2022 [English: Report on The State of Education 2022], Inspectie van het Onderwijs