What’s involved in launching a new school? This week, Indrek Lillemägi looks back on his experiences working on the development of a new upper secondary school, Tallinna Pelgulinna Riigigümnaasium, that opened in Tallinn, Estonia in the fall of 2023. Previously Lillemägi was the founding principal of a private school in Tallinn, the Emili Kool (named for Jean Jacques Rouseau’s book Emile, or On Education) that opened in 2016. In the first part of this two part interview, Lillemägi discusses some of the key steps in the development of the upper secondary school and some of the lessons he learned from his earlier experiences in establishing the Emili Kool. In the second part of the interview, Lillemägi describes what it was like to lead the Emili Kool through the first part of the COVID pandemic in Estonia.

This interview is one in a series exploring what has and has not changed in education since COVID. Previous interviews and posts have looked at developments in Italy, Poland, Finland, New Zealand, the Netherlands, South Africa, and Vietnam. This interview with Lillemägi was conducted by Thomas Hatch in May of 2023, a few months before the Pelgulinna Riigigümnaasium opened. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Thomas Hatch (TH): Can you give us a sense of what it’s been like to develop a new upper secondary school in Estonia? What were some key milestones or challenges leading up to your opening in September of 2023?

Indrek Lillemägi (IL): We started with a little over 400 students in the 10th grade in the fall of 2023. We will add an 11th grade this year, and a 12th grade next year, and we will end up with a school with about 400 students in each grade at the upper secondary level. So it will be a big school, with more than a thousand students.

But this new school is part of a longer story because it’s one of a series of new State-run gymnasiums or upper secondary schools that the Ministry of Education has created in some municipal centers over the past 10 years as populations decreased. But Tallinn is another story because their population is increasing, without enough places in upper secondary schools, so three new gymnasiums were approved. The Ministry of Education then hired me along with two other new headmasters to create the schools together, so I’m not working alone. We worked in the same room every day, and we did a lot of things together. We’ve hired people together. We’ve developed communications together. We’ve done a lot of bureaucracy together. We’ve shared a lot, but we also had our own communities to serve. Of course, we are also different as principals and as humans, and we have different things we believe in, so the schools are pretty different. But in the process, we were together.

TH: These state-run gymnasiums will function along with the upper secondary schools run by the municipalities?

IL: Yes, exactly. We are the extra ones, and none of the municipal schools will close because of us. But, after 5-6 years when student numbers decrease again, the municipality may have to make some tough decisions, and they may have to close some schools.

For the new schools, the Ministry gave us full autonomy. They just said “this is the budget; this will be the new school building of yours; and these are the regulations.” We were given full leadership autonomy to build our schools. It’s enormous trust that they had in us. I don’t think that’s possible in any other country. We also had the full support from the Ministry of Education. We had all the lawyers, all the experts, helping us.

“[T]he Ministry gave us full autonomy. They just said, “this is the budget, this will be the new school building, and these are the regulations. We were given full leadership autonomy to build our schools.“

When I first started writing down the strategy for building a new school, I tried to understand what’s going on? What’s going in education in Tallin? Of course I had some knowledge, but I had time to really talk to people, different school heads, different teachers, and parents and also with the local community where my school would be located. I tried to understand what’s missing because I really believe that strong educational systems are heterogeneous. Students and parents should be able to choose their school according to their values or principles. So I didn’t want to copy the “best school.”

TH: Were the regulations specific to the new schools or are you referring to the general regulations?

IL: Just the general regulations. But I have to say, we were even pushed to try out the borders of the regulations or touch the “grey zone.” I think the Minister of Education sees us as being able to try out more new things, and then our experience can either be transferred to other places or they can be taken as a lesson.

TH: How did they push you or encourage you to take those risks?

IL: It wasn’t anything official, but it was through our weekly meetings with some of the those involved with the management of state schools. The schools include the new state gymnasiums but most of the schools that are managed directly by the state are schools for students with special needs or vocational schools.

TH: So from there, what was your journey?

IL: From there, I tried to combine three things. One was what I was hearing from the local community in Northern Tallinn where the school would be. They tend to be very socially active, and the local citizens want to be involved. Second, a lot of students told me about the challenges in their lives that do not have any part in their education. Mostly, the students talked about stresses related to climate issues and their mental health. They said, “these are big things in my life, but I don’t deal with these things at school.” These stories from the students really influenced me.

“A lot of students told me about the challenges in their lives that do not have any part in their education. Mostly, the students talked about stresses related to climate issues and their mental health. They said ‘these are big things in my life, but I don’t deal with these things at school.‘”

Then of course there were my own passions and things that I am interested in. When I started writing down what kind of school I would like to have, I wrote down that the focus of the new school would be about dealing with the problems that do not have easy solutions – questions of climate and the environment and questions of democracy and how to build strong democratic institutions. I set these as the focus points of the school. Of course, I didn’t write down any specific details about the curriculum; I just wrote down the principles for myself. Now, the values of our school are based partly on these principles.

Then when I was hiring the head teacher, I showed the candidates the paper with the principles, and I asked them: “Would you like to work for that?” A lot of people applied for this position, and I hired someone who had been working last nine years in Netherlands in an International School. After she moved back to Estonia, we started working together and talking together about the curriculum about the learning methods, and about the other focus points of our school. Eventually, we hired a team of eleven people who worked on building everything from the curriculum to the bureaucracy. We then started hiring the rest of the staff when we started dealing with student applications and everything else.

TH: What are the focus points of the other schools?

IL: Ours is democracy and environment, solving complex problems. One school that’s located near the Technical University in Tallinn focuses on technology and science, and the third school third focuses on self-expression.

We also met with the heads of the other two new schools to talk about what could bring these three new schools together. We decided that, for all of them, the curriculum would allow students to create their own individual learning paths. We wanted our students to be able to put together their own curriculum and to have much more choice compared to the average school. Because of that, we created a network of courses that could be shared between these three schools. Now, the students of one school can take courses at the other two schools as well. These are elective or “selective” courses. Some are online, but many are in-person. Most of the selective courses are on Thursdays when students can move between schools, and when students can choose which courses to take or what internships or other activities to participate in. That means we have to coordinate our schedules with local universities, vocational schools, and NGOs as well. But now, on Thursdays, our students can move around the city between morning course time and afternoon time. If a student goes to the university, they stay there half the day. The other days are more conventional with 70-minute lessons. Less conventional is an 80-minute midday break when students again have more responsibility for deciding how to use their time. In addition to lunch, they can use the time to rest, to do group or individual work, or go the gym or on walks.

TH: Are there other unusual aspects to your school day?

IL: The first two weeks don’t follow the regular schedule. Students go through an onboarding program where we take them through a narrative arc that goes from the Big Bang to civilization’s end. They build relationships and learn about the school’s approach and theory of knowledge – how different fields do research and gain knowledge. It’s a completely different two-week program than most students have had before. The other two schools have a similar onboarding approach, though it’s slightly shorter. Teachers from all three schools worked together to develop the approach.

We also have mentoring groups in which a teacher meets with a group of about 18 students which is smaller than the average class size. The mentoring groups have weekly lessons to reflect on social-emotional and group challenges. The mentors are the regular subject teachers, but we also provide them with special training. These kinds of mentor groups are becoming more common in the state gymnasiums.

TH: What were some of the key lessons from your work founding the Emili School that you brought to your work with this school?

IL: This may sound like a cliches, but of course, the relationships are the most important. Everything in education starts from building relationships, first with one student. Then building a strong community and strong relationships with the local parents, grandparents, local NGO’s, local businesses, and so on. I knew these things, but I didn’t have the experience of how to involve all these people, how to make them understand everyday life in a school and the challenges in a new school.

TH: What were some of the things you learned to do to help build those relationships?

IL: One of the key lessons was that I started being more and more honest. In the beginning, I felt responsible for “selling” the school – I talked a lot about the vision and ideas. But, later, I also started talking honestly about the challenges, the difficulties, even the problems we faced. I began to understand that being honest built much stronger relationships, so people who joined our community were not disappointed later on – they had the transparent view before joining.

“I began to understand that being honest built much stronger relationships, so people who joined our community were not disappointed later on – they had the transparent view before joining.“

TH: What were one or two of the biggest challenges you faced when you were starting that school?

IL: Probably that private education in Estonia is uncommon – less than 5% of students go to private schools. So parents think “private school” means a paradise school with no problems. The challenge was that in the beginning we were a normal school with the same challenges and growing pains all new organizations have. As I started telling a more honest story, with open school days where parents and community members could visit, I think they began to see and appreciate the hard work and emotions teachers go through, and they developed a better appreciation for the work the school was doing.

TH: Was there a particular issue parents were surprised about, or was it just in general they expected perfection?

IL: Probably the emotions throughout the school day was something they talked a lot about, especially in primary school. There’s someone crying; someone’s sad; someone’s telling a story about their weekend – it’s full of emotions. And they saw the teachers trying to be really empathetic, trying to support all the students – the sad ones, the crying ones – and I think that was surprising to them. And I think parents often expect teachers to have free time during breaks. But especially in a starting school with new methods, we were doing a lot of preparation and a lot of reflecting and learning together. Parents expected teachers to have more free time than they actually did.

TH: Can you share a bit about how you planned to assess student outcomes and your progress in developing the school?

IL: That’s a big topic! We’re bringing many innovations together like much more collaborative teaching. As an example, in the 10th grade we have two “pillars” – one for natural sciences and one for cultural studies. In the natural sciences, the biology teacher, geography teacher, physics teacher, chemistry teacher, they all work together. We have also changed the national curriculum by changing the order of the learning outcomes so it’s more much more integrated than usual. Teachers often just follow the textbooks but the textbooks in different fields don’t go together very well. Some of the topics are really similar in geography, in physics and chemistry, but they are learned in different times in the different fields so students have trouble putting the big picture together. Our science teachers worked together for almost a year before the school opened, and they’ve done a lot of work reordering the national curriculum learning outcomes. That means they have to design assessments that align to those more interdisciplinary learning outcomes. It all starts from the dialogue and from feedback based on these learning outcomes.

Besides descriptive feedback, we use percentages from 0-100 rather than letter grades. But what’s different is that the students get one percentage for all the sciences, not a separate percentage for each subject. All of this influences the learning process because the teachers have to work together to create the final assessment or final project; they assess it together; and they plan together.

But at the end of 12th grade, the regulations still require us to give the students marks in each of the subjects. We do use pre-tests in the subjects, some of these are provided by the State, but the pre-tests and final subject tests are just for reflection for the students and teachers, they don’t influence their school marks in each pillar.

TH: How did other schools in Tallinn react to your planning to develop these new State gymnasiums?

IL: There been different emotions. We heard that some Directors or Head Teachers told their teams some horror stories about us, but some of them were really supportive. Some of the Directors have asked us to come to their schools to explain everything about the school to the students, so really different approaches.

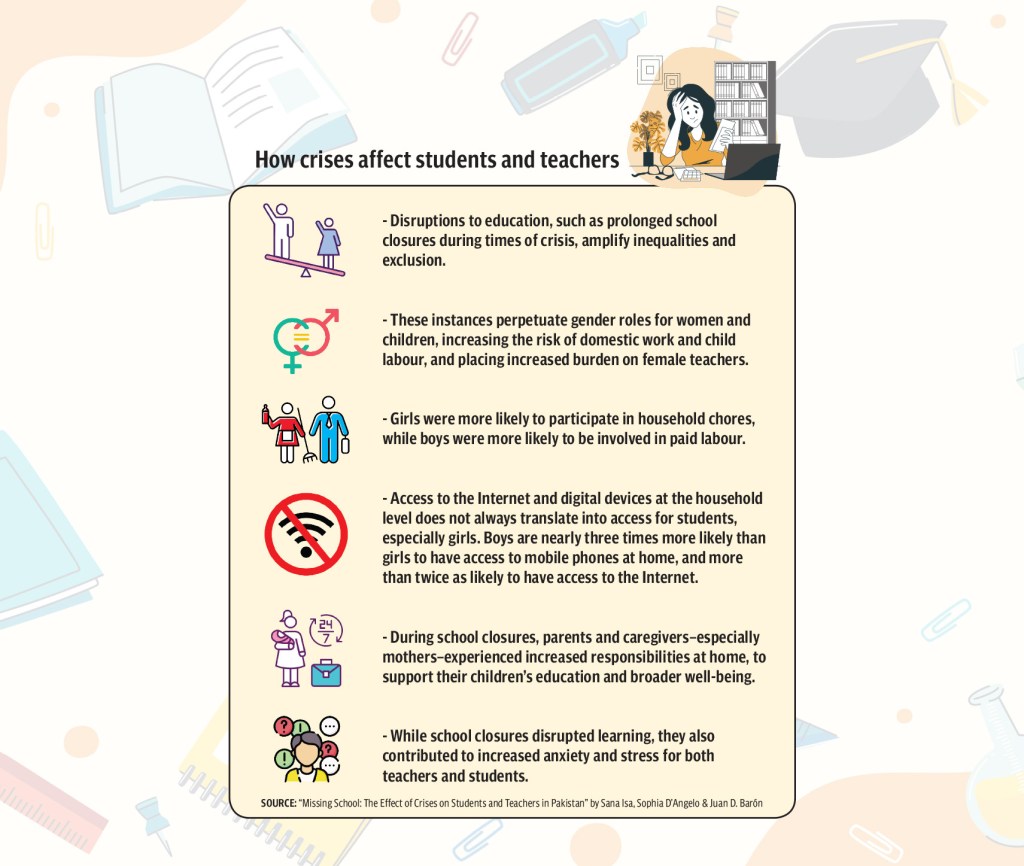

Next Week: Leading a school in a context of uncertainty: Indrek Lillemägi discusses the COVID-19 school closures in Tallinn, Estonia