In part 3 of this 3-part interview, Hirokazu Yokota shares his personal reflections on his experiences helping to establish the new Children and Families Agency (CFA) and, previously, the new Digital Agency. In Part 1, Yokota described the development of the CFA and the efforts to promote digital transformation in childcare, and in Part 2, he discusses some of CFA’s current initiative. Yokota has followed a rare career path as a bureaucrat who belongs to the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), but who has repeatedly stepped out of the “education circle” to work in other agencies, including the Children and Families Agency, which was established in April 2023. In September 2021, Yokota was one of the charter members who helped launch Japan’s Digital Agency , and he went on to work as a Deputy Superintendent in Today City. Yokota has previously written about his experiences as a parent and educator during the pandemic as well as his work in the Digital Agency and in Toda City: A view from Japan: Hirokazu Yokota on school closures and the pandemic; Hiro Yokota on parenting, education and the new Digital Agency in Japan; and Hirokazu Yokota on aggressive education reforms to change the “grammar of schooling” in Toda City (part 1) and (part 2). Please note that Yokota is sharing his personal view on CFA and its policies, and his views do not represent the official views of the government. For further information contact him via Linkedin.

IEN: Can you share your personal take on the initiatives by CFA – how is it working? What have you found most exciting, most challenging? What’s next for the agency/society?

HY: It is precisely because these are newly established organizations that they are able to advance policies that would be difficult under the framework of existing institutions. For example, the number of staff at the Digital Agency increased from 571 at the time of its establishment in September 2021 to 1,013 as of July 2023. The government has set a goal of further expanding this to approximately 1,500 personnel. Similarly, the Children and Families Agency’s budget has grown significantly: from approximately JPY 4.8 trillion in FY2023, to approximately JPY 5.3 trillion in FY2024, and to approximately JPY 7.3 trillion in FY2025 with the launch of the “Children’s Future Strategy” (Kodomo Mirai Senryaku) and its “Acceleration Plan” (Kasokuka Plan). Thus, it now far exceeds the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) budget (approximately JPY 5.3 trillion in FY2024 and JPY 5.5 trillion in FY2025). Such dramatic increases in staffing and budgets were made possible precisely because these were newly created agencies.

Also, last December we published “New Direction of Childcare Policy,” which details specific policy measures that should be taken in the next five years. There are so many workloads ahead, but I am very excited to take on these new tasks to fully realize the “child-centered society.”

Personally, during my time at the Digital Agency, I worked alongside many private-sector professionals, from developing priority plans for the realization of a digital society to promoting digital transformation in the fields of education and child-rearing. From them, I learned a great deal about flat information sharing and interactive meeting styles, which are common in the private sector. Later, when I was seconded to the Toda City Board of Education as Deputy Superintendent and Director of the Education Policy Office, I was able to take on many “zero-to-one” challenges — such as implementing the use of educational data in schools and piloting one-on-one meetings and reflection workshops to foster a flat organizational culture — things I might not have been able to do if I had remained in MEXT.

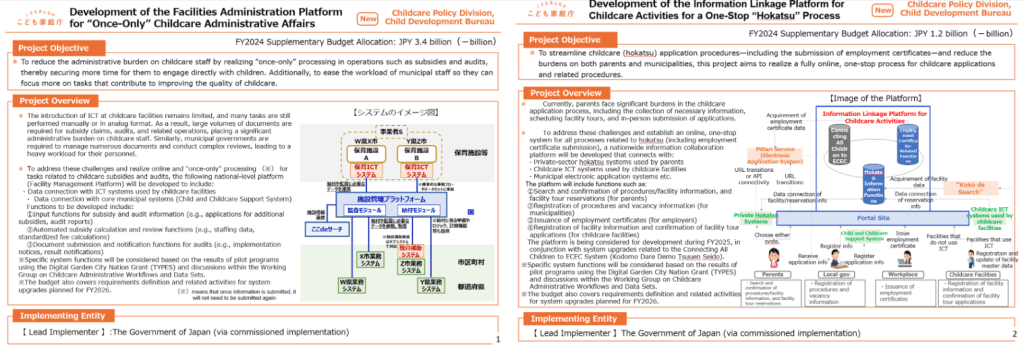

Now, as I lead digital transformation (DX) initiatives in the field of childcare at the Children and Families Agency, I feel that the “practical knowledge” I gained from my experiences at the Digital Agency and in Toda City is proving immensely valuable. As with the Digital Agency, we are advancing childcare DX projects with a mixed team of public- and private-sector personnel using a project-based approach. In this work, I constantly strive to serve as a bridge connecting “policy (systems)” and “technology (systems).” These two are two sides of the same coin: without a deep understanding of both, it is impossible to build effective structures. Given my background traversing the traditional bureaucratic divides between policy and systems, I believe that my ability to connect civil servants knowledgeable about policy and politics with private-sector experts skilled in technology is a unique value I bring. While minimizing risks, I find great purpose in leading the highly challenging task of building two entirely new national information systems in the childcare sector.

However, there is something I personally feel about the challenges faced by new organizations like the Digital Agency and the Children and Families Agency. In these organizations, the individuals who often receive public attention are those recruited from the private sector (e.g., the Digital Agency note and an article of CFA staff). Of course, I fully understand that highlighting these individuals is a necessary strategy to attract talented people from the private sector to public service. Still, it must not be forgotten that there are also many government officials—those who may not be in the spotlight—working diligently and persistently to realize a digital society and a child-centered society. During the foundational periods of these agencies, I witnessed firsthand many civil servants who unfortunately had to take leave due to overwork or mental stress. There were times when I blamed myself, wondering if I could have done more to support them. It is easy to criticize bureaucrats. That is precisely why I strongly hope that the media will shine more light on those government employees who, despite struggling to adapt to cultures different from their home ministries, are working earnestly for the public good in these new organizations. In the United States, there have been mass layoffs of federal employees. Precisely because of that, I believe that Japan should reaffirm its respect for civil servants who serve behind the scenes as the “unsung heroes” supporting public service.

“I believe that Japan should reaffirm its respect for civil servants who serve behind the scenes as the “unsung heroes” supporting public service.“

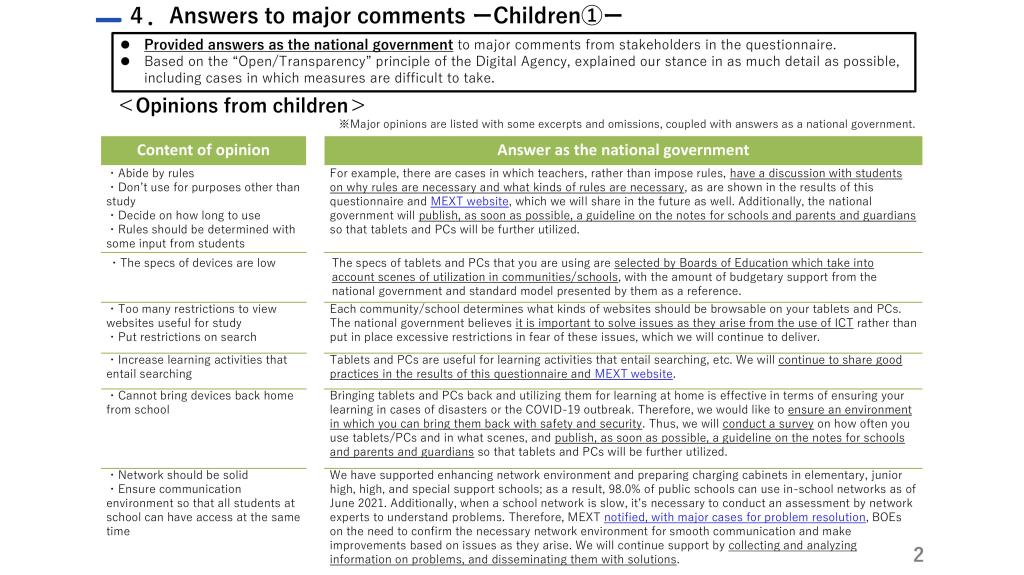

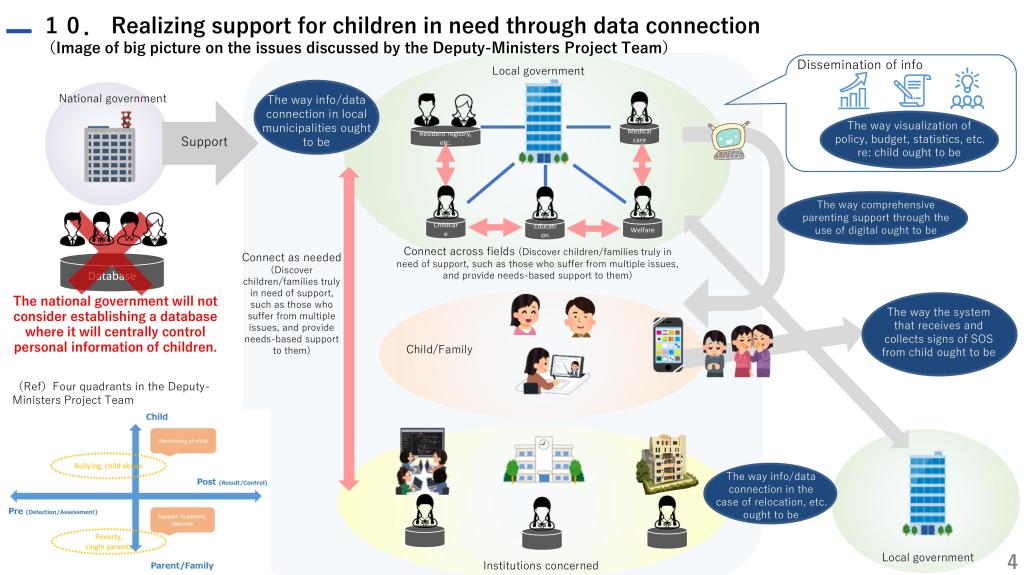

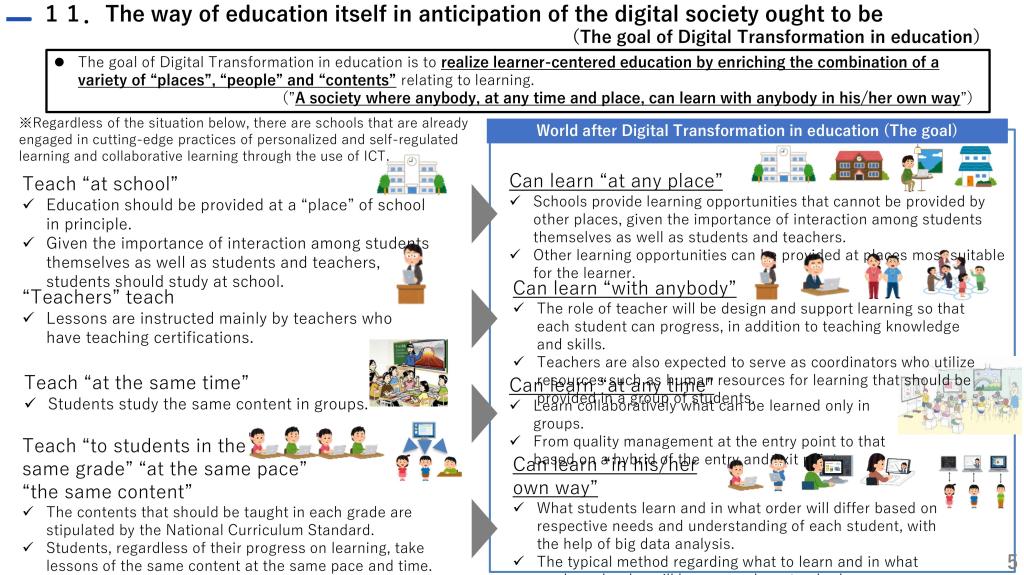

Looking toward the future, at the Children and Families Agency, we are now challenging ourselves to directly listen to the voices of children and young people through various channels and reflect their opinions in policy. In doing so, I believe it is necessary to proactively reach out to “those whose voices are not being heard” — the children and young people who have not yet had the chance to sit at the policymaking table. Constantly being aware of who is not at the table and delivering support in a proactive (“push”) manner, combined with respect for civil servants working behind the scenes, will surely help make this country better.

Furthermore, it is extremely important to make the policy methods developed by the Digital Agency and the Children and Families Agency the new norm across all of Kasumigaseki (the Japanese government). When I shared new policy challenges that I was working on, I occasionally heard comments, even from those inside the government, such as, “You could only do that because you’re in a new agency like the Digital Agency or the Children and Families Agency.” I believe that kind of thinking is truly unfortunate. One day, when I return to MEXT, I want to prove that it is not because of the agency’s novelty, but because each and every civil servant, with a sense of purpose and a little courage, can make change happen.

“[I]t is not because of the agency’s novelty, but because each and every civil servant, with a sense of purpose and a little courage, can make change happen.”

Next Week: From foundational learning to colleges and careers: Critical educational issues in India post-pandemic (Part 1)