The third part of IEN’s annual scan of the back-to-school headlines highlights some of the issues that states and cities in the US are facing as students have returned to school. The first part of the scan shared stories from outside the US, and the second part gathered stories about some of the many policy changes, demands, and cuts that schools in the US are having to respond to this year.

For back-to school headlines from Fall 24: Politics, Policies, and Polarization: Scanning the 2024-25 Back-To-School Headlines in the US (Part 1); Supplies, Shortages, and Other Disruptions? Scanning the Back-to-School Headlines for 2024-25 (Part 2); Banning Cell Phones Around the World? Scanning the Back-to-School Headlines for 2024-25 (Part 3); Fall 23: Crises and Concerns: Scanning the Back-to-School Headlines (Part 1), (Part 2), (Part 3). Fall 22: Hope and trepidation: Scanning the back-to-school headlines in 2022 (Part 1), (Part 2) , (Part 3); Fall 21: Going back to school has never been quite like this (Part 1), (Part 2), (Part 3); Fall 20: What does it look like to go back to school? It’s different all around the world…; Fall 19: Headlines around the world: Back to school 2019 edition.

The many funding cuts, executive orders, and other demands from Washington dominated the local school headlines in the US this year, including fears that students might be deported and ICE agents may target schools. But a few of the usual concerns were covered as well, including concerns about the economy, the costs of supplies, and growing concerns about cellphones, AI, and other technologies.

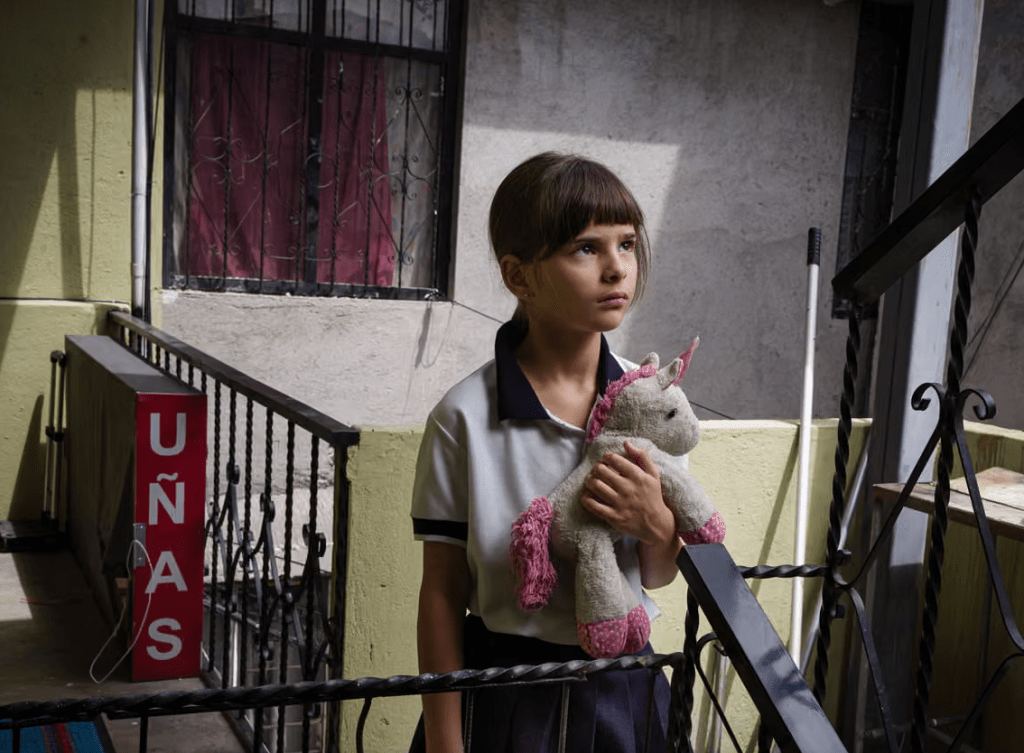

Fears & Deportations

Immigrant Families Fear Trump’s Deportations as Children Return to School, ABC News

For Mixed Status Families, Deportation Fears Cast Shadow Over New Academic Year, NPR

‘So Many Threats to Kids’: ICE Fear Grips Los Angeles at Start of New School Year, The74

What Mass. Schools are Saying About Immigration Enforcement as Students Return, NBC Boston

Federal Surge has Taken a Toll on Children of Immigrants in Washington, PBS

Costs & Supplies

Back-to-School Prices are a Mixed Bag this Year, NBC News

Parents Say Back-to-School Feels Pricier than Ever, with Many Spending $500+ on Supplies and Activities, Yahoo News

Teachers are Spending More and More on School Supplies. Here’s Why, Indiana Capitol Chronicle

3,000 Teachers Beg for Donations for Basic Classroom Supplies — Despite NYC’s Record-Breaking per-Pupil Spending, New York Post

School Lunches Are Costing Families More Than Ever: Here’s Why, Daily Voice

Cellphones, AI & EdTech

Most Students Now Face Cellphone Limits at School. What Happens Next? Education Week

“A wave of bills passed into law this year, and now 31 states either already limit or ban students from using their personal devices in school or plan to do so for the 2025-26 or 2026-27 school years.” – Education Week

More Students Head Back to Class Without One Crucial Thing: Their Phones, NPR

Students Turn Back to Books as More School Districts Implement Phone Bans, Newsweek

6 Ways Administrators are Handling Cellphone Bans in the New School Year, K-12 Dive

From ‘Bring It On’ to ‘This Policy Is Crazy,’ NYC Parents React to Cellphone Ban, The74

“Families with older students are most likely to oppose the blanket edict; others say a one-size-fits-all approach needs to be changed.” -The74

‘The New Encyclopedia’: How Some Kids Will Use AI at School this Year, CNN

ChatGPT Usage Skyrockets as Kids Return to School, Newsweek

Back to School: AI in the Classroom, the Negative Side, WNEP

Major Partnerships are Expanding K-12 AI Literacy, EdTech

“K-12 schools are increasingly tapping new training resources to aid AI integration. For example, the National Academy for AI Instruction — a partnership of the American Federation of Teachers, Microsoft, OpenAI and Anthropic — aims to use a framework co-developed with OECD and Code.org to equip educators, especially those in remote areas, with a mix of in-person and online modules to develop teacher fluency and literacy in AI.” – EdTech

Back-to-School Season Brings Spike in Cyberattacks, EdTech

“August and September DDoS attacks are twice as bad as June and July for the education industry, as hackers know that the busy back-to-school time means staff are distracted and adjusting to new routines. NetScout’s Threat Intelligence Report ranked educational support services as the third-most-attacked industry in the last half of 2024.” – EdTech

Driver Shortage: Dozens of School Bus Route Cancellations Hit Mat-Su Students, KTUU

Arkansas

Arkansas School District Responses to Ten Commandments Law Mixed, Arkansas Advocate

California

California Schools Brace for Fallout from U.S. Supreme Court Decision on Religious Rights, EdSource

California Bill Requires Schools to Alert Families of Immigration Agents on Campuses, The Guardian

Colorado

Denver Schools Chief: Trump Administration is Weaponizing Title IX and Pushing ‘Anti-Trans Agenda’, Chalkbeat

Illinois

Chicago Public Schools Prepare for National Guard Threat, Chicago Tribune

About 200 Students with Disabilities Still Need a Classroom in Chicago, Chalk Beat

Florida

In the Name of Parental Rights, New Law Requires Sign-Off for Corporal Punishment in Florida Schools, Florida Phoenix

‘It’s quite honestly amazing that this hasn’t previously been in place in Florida.’ – Florida Phoenix

Florida Schools Will Test Armed Drones this Fall to Thwart Shooters , K-12 Dive

Massachusetts

What Massachusetts Parents Should Know this Back-to-School Season, Boston Globe

Boston Mayor Wu Expects Deportation Fears to Affect Boston School Attendance, WBUR

Michigan

Michigan Schools will have New Requirements for Teaching English Learners this School Year, Chalk Beat

“The new state protections come as the federal government is pulling back its support for English learners.” – Chalk Beat

Minnesota

Minnesota Schools Adjust Breakfast Menus to Abide by New Federal Sugar Restrictions, Minnesota Star Tribune

Nebraska

Nebraska Students Adapt to Cellphone Ban in Schools, KETV

New Jersey

Newark Students Head Back to School. What’s New this School Year? Chalk Beat

“This school year marks Newark’s fifth year under local control. District leaders celebrated the opening of the district’s newest trade high school.” – Chalk Beat

New York

Adirondack Educators Contend with Dwindling Resources as Enrollment Dips, Times Union

Thousands of New Teachers to Start as NYC Pushes Historically Large Hiring Spree to Shrink Classes, Chalk Beat

“Topics that loomed large at New York City’s teacher orientation included the state class size law, the school cellphone ban, and curriculum changes.” – Chalk Beat

What to Know About Vaccines in NY as Students go Back to School, Gothamist

New N.Y.C. Food Standards Could Spell Doom for Chicken Nuggets, New York Times

Free Haircuts for NYC Kids Ahead of First Day of School, PIX11

Ohio Students Face New Cellphone Ban as School Year Begins, WBNS

Families, Staff Return to School Across Oregon, Some Under Fear of ICE Arrests, OPB

What to Know About Cellphones and Artificial Intelligence as Oregon Students Return to School, OPB

“The new statewide cellphone ban takes effect this school year, as educators continue to learn how and when to use AI.” – OPB

Pennsylvania

As Classes Begin, Pennsylvania School Districts Feel Pinch of Budget Impasse, York Dispatch

Two Susquehanna Township (PA) Schools Cancel Classes Due to Lack of Bus Drivers, WGAL

South Carolina

‘Why Don’t I See my Friends Anymore?’ Parents Fear Deportations are Coming to SC Schools, The Post and Courier

Tennessee

Gun safety classes required, starting in kindergarten, in Tennessee this year, Washington Post

Texas

‘A No-Win Situation’: How Houston School Districts are Responding to the Ten Commandments Classroom Law, Houston Chronicle

Trump’s Immigration Crackdown Upends Life at Austin Elementary School, Austin American-Statesman

Washington D.C.

‘Leave Our Kids Alone’: DC School Year Starts Amid Armed National Guard Patrols, NBC 4 Washington

Parents Mobilize to Protect School Commutes Amid Trump Deployment in DC, Bloomberg

Schools Reopen in D.C. With Parents on Edge Over Trump’s Armed Patrols, Education Week

Washington

Washington State District Finally Opens School After Support Staff Strike, The 74

“Schools in Washington state’s Evergreen district finally opened for the year Friday, after a strike by support staff delayed the start of school by nearly three weeks. About 1,400 paraprofessionals, bus drivers, security guards, maintenance workers and other members of Public School Employees of Washington SEIU Local 1948 had walked off the job over contract negotiations that had gone on for six months. District teachers refused to cross the picket line. Lauren Wagner reports.” – The 74

Wisconsin

As Costs Rise, Wisconsin Teachers and Families Pay the Price on Back-to-School Supplies, The Wisconsin Independent

“The inflation, tariffs and lagging school funding in Wisconsin are causing parents and educators to take more caution when back-to-school shopping this year” – The Wisconsin Independent