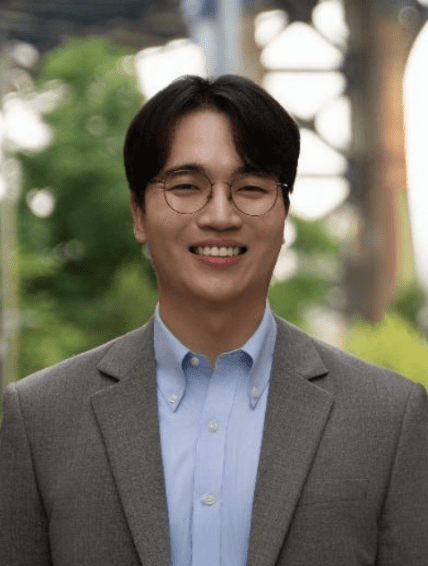

In February’s Lead the Change (LtC) interview, co-editor Dr. Soobin Choi argues that meaningful educational change requires confronting the structural inequities, while continually recommitting to inclusive, participatory reform. The LtC series is produced by co-editors Dr. Soobin Choi and Dr. Jackie Pedota and their colleagues at the Educational Change Special Interest Group of the American Educational Research Association. A PDF of the fully formatted interview will be available on the LtC website.

Lead the Change (LtC): The 2026 AERA Annual Meeting theme is “Unforgetting Histories and Imagining Futures: Constructing a New Vision for Educational Research.” This theme calls us to consider how to leverage our diverse knowledge and experiences to engage in futuringfor education and education research, involving looking back to remember our histories so that we can look forward to imagine better futures. What steps are you taking, or do you plan to take, to heed this call?

Dr. Soobin Choi (SC): To heed the call of unforgetting histories, we must begin with a seemingly cynical truth: if the same question had been posed thirty years ago—or if it is posed thirty years from now—the “imagined futures” offered by scholars would likely be hard to distinguish. Educational reform is rarely about inventing entirely new futures. The purposes of public education remain stable; the grammar of schooling reasserts itself; and reform rhetoric cycles far faster than our classrooms ever change (Payne, 2008; Tyack & Cuban, 1995). Across decades, our bright futures rhyme: broaden opportunity, improve learning, and prepare young people for civic and economic life. That was true then, is true now, and will be true later.

Many of our thorniest issues persist not because we lack the technical expertise to solve them, but because we quietly, yet deliberately, choose not to decide on them. In this light, “unforgetting histories” is a process of cyclical tinkering with not only what we decide to do, but also what we decide to leave undecided. We frequently opt for a nondecision, limiting the scope of our inquiry to “safe” or “bipartisan” issues, effectively keeping controversial structural challenges off the research and policy agenda (Fowler, 2012). Both unforgetting and forgetting are elaborately intentional; today’s “unforgetting” often collides with yesterday’s institutionalized forgetting.

The school is a particularly apt site for this intentional forgetting. We treat persistent “base” problems as fixed, natural laws rather than political choices. Through a Marxist lens, the Base represents the economic organization of society—productive forces and relations of production—while the Superstructure includes the law, politics, and, crucially, schooling (Althusser, 1971). Historically, reforms repeatedly ask the school (the superstructure) to fix problems rooted deeply in the base—inequality in wealth, housing, and health—while our governance routines keep the hardest structural issues off the actionable agenda (Labaree, 2012).

Our system becomes increasingly bifurcated, characterized by extreme wealth concentration and precarious labor (OECD, 2024). The system makes a persistent nondecision to leave funding structures, property-tax-based inequities, and competitive sorting mechanisms untouched. This recurring forgetting—the refusal to acknowledge how structural realities bound what schools can achieve—is a form of institutional amnesia in which we should refuse to participate (Pollitt, 2010). The result is a cycle where we task the school with the impossible job of “fixing” a society whose base we refuse to reform.

While this may sound unsparingly candid about the past we have made and the present we inhabit, I am more than willing to embrace this cyclical tinkering as a pleasant journey. To truly “unforget” history is to recognize that a bright future in education is not a static destination, but a perpetual challenge and response cycle (Toynbee, 1987). Borrowing from Arnold Toynbee, we must understand that civilization—and by extension, futuring for education and education research—“is a movement and not a condition, a voyage and not a harbour (Toynbee, 1948, p. 55).” Our collective, consistent effort to tinker is the very essence of this voyage. The sameness of our aspirations across generations is not a sign of failure; it is our most profound way of unforgetting. It is the continuous re-commitment to a bright future that may never be reached in its totality, but is nonetheless worthy of walking toward.

This is where we must transition from the tragic endurance of Sisyphus to the affirmative creative will of the Übermensch. Nietzsche’s Übermensch does not merely endure the “eternal recurrence” of the struggle; they will it (Nietzsche, 1974). We find value not in the arrival at a harbor, but in the power of the voyage itself. As a researcher, educator, and citizen, I plan to heed the AERA call by adopting this posture of active affirmation. I choose to view the repetitive nature of our work not as redundant labor, but as a sacred act of “unforgetting.” My work aims to re-affirm human dignity and possibility against a mechanical system. We tinker not because we are naive enough to believe in a final utopia, but because the act of tinkering is itself a refusal to let the spirit of education decay into static inertia. We walk toward the bright future not because we expect to arrive, but because the walk itself is the only way to remain truly awake to our history and our potential.

“We tinker not because we are naive enough to believe in a final utopia, but because the act of tinkering is itself a refusal to let the spirit of education decay into static inertia.”

LtC: What are some key lessons that practitioners and scholars might take from your work to foster better educational systems for all students?

SC: To build a better educational system for all students, we must, above all, establish systems and provide leadership and policy support that empower every student and their family to participate in the school improvement process. Listening to their diverse opinions and experiences and reflecting them in school reform and change is indispensable for creating a school that truly serves everyone (Choi, 2023). As with all human relationships, if we do not listen, we cannot know what is desired or what is lacking; solutions proposed without listening are inevitably prone to prejudice and misunderstanding. Furthermore, when students and families feel that no one is interested in their perspectives, or when they lack a channel to express them, they cannot help but feel alienated and marginalized. It is when someone genuinely listens to our stories that we feel respected and recognized as true members of community.

Although communication with the school through teachers, principals, or counselors is crucial for student development, this access is unfortunately closer to a privilege for certain groups rather than a universal benefit enjoyed by all. In many countries—not just the United States—student diversity is rapidly increasing, yet the teaching workforce remains highly homogeneous, largely mirroring the dominant groups in society. While approaching a teacher to strike up a conversation or share a concern is easy for some students, it is a source of endless hesitation for others. Similarly, asking about a child’s school life comes naturally to some parents, but for others, it is virtually impossible—whether due to the social and psychological distance from educators or simply a lack of time owing to the relentless demands of making a living.

To truly listen and guarantee the opportunity to speak, we must narrow the gap between schools, students, and homes. Most of my research contributes to bridging this distance between educators and the students they serve. Through professional development, teachers can come to recognize that students’ racial/ethnic, linguistic, and cultural diversity are tremendous assets for learning and development (Choi & Lee, 2020; Choi & Mao, 2021). By integrating this diversity into the classroom, educators can ensure that individual students feel valued, expand their own worlds through their differences, and gain opportunities to understand those unlike themselves (Gay, 2002; Ladson-Billings, 1995). To foster this growth of teachers, principals can exercise leadership that actively supports the classroom environment and creates collaborative spaces for teachers (Choi, 2023; Choi et al., in press). Furthermore, students themselves can become agents of change in building a culturally inclusive school climate, ensuring that marginalized groups feel a genuine sense of belonging (Choi et al., 2025b). Just as it is vital for schools to embrace diverse opinions and values, my research contributes to ensuring that diverse voices, perspectives, and learning opportunities are included in how we evaluate schools and their leadership (Choi, 2025; Choi et al., 2025a; Choi & Bowers, 2026; Lee et al., 2025).

LtC: What do you see the field of Educational Change heading, and where do you find hope for this field for the future?

SC: To understand where the field of Educational Change is heading, we must confront the resistance it currently faces. Unfortunately, we live in a world where acknowledging and promoting the value of diversity is not always embraced, and is sometimes even actively threatened. The field is heading toward a necessary, defining confrontation with a skeptical question: Is carefully listening to individuals truly tantamount to turning our backs on the majority?

This is precisely where I find my greatest hope for the future. Contrary to the logic of exclusion, the evidence shows us a brighter reality. My research demonstrates that when educators actively leverage the value of individual students’ diversity, the learning climate of the entire school actually improves (Choi & Lee, 2020). I find hope in the empirical truth that equity is not a zero-sum game, but a rising tide. As William Blake (1863) wrote, “To see a world in a grain of sand / And a heaven in a wild flower”—I would argue that our hope for the future lies right here. The very first step toward creating a school for all students is acknowledging the profound value of each and every difference.