What’s in the education news as the school year begins in many parts of the Northern Hemisphere? This week, in part 2 of IEN’s annual back-to-school scan, we share the headlines from across the US and around the world that touch on issues like the costs of supplies and other materials for parents as well as teachers; hot weather and other disruptions; shortages – particularly of bus drivers in the US; and a variety of other topics. In Part 3, we will gather together some of the many stories discussing cell phone bans, particularly in the US and Canada. Last week, Part 1 of this year’s scan provided an overview of some of the many election-related education stories that have appeared in the press as students return to school Politics, Policies, and Polarization: Scanning the 2024-25 Back-To-School Headlines in the US (Part 1).

Back-to-school headlines around the world

Clash between tech and textbooks as Canadians head back to school, CityNews

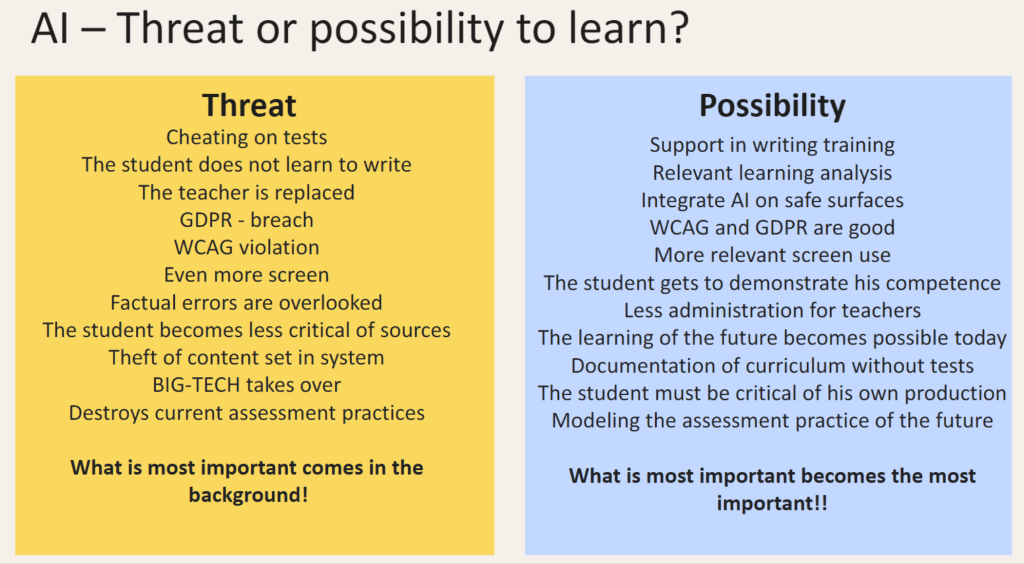

Back to school could mean back to the hot seat for Big Tech. Social media platforms TikTok, Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat spent last school year embroiled in a lawsuit accusing them of disrupting learning, contributing to a mental health crisis among youth and leaving teachers to manage the fallout. When students return to class this September, experts say the clash between tech and textbooks will be reignited

French teachers wrangle with new reforms as children return to classroom, FRANCE24

Summer holidays end for school children in the south of the Netherlands, Dutch News

French teachers wrangle with new reforms as children return to classroom, FRANCE24

Ukrainian front-line students celebrate back-to-school despite ever-present air raid alarms, Local10

Ukrainian children return to school in underground shelter amid Russian bombardments, Firstpost

Thousands of Children Cut off from School by North Vietnam Floods, Cambodianess

Education Costs/Supplies

Thousands of children will struggle to return to school because of North Vietnam floods, CamNess

Back to school: Which of Europe’s ‘Big Five’ countries pays the most for school supplies?, Euronews

Although textbook prices vary from school to school, they add a substantial burden: €591,44 on average in Italy and €491.90 in Spain, the highest ever

Rising cost of living puts pressure on parents’ back-to-school finances in Germany, Euronews

Moroccan Families Break-the-Bank as Children Return Back-to-School, Morocco World News

Families with multiple children, in particular, are struggling to balance their budgets as they manage not only the cost of school supplies but also additional needs such as furniture and other essentials for their children.

Back-to-school spending averages $586 per student, Yahoo Finance

Educators Prepare Early, Spend Their Own Money for New School Year, Education Week

Shortages

Some districts are still struggling to hire teachers for the new year, Education Week

‘They have to have known’: Hawaii scrambles for solutions to bus driver shortage, Honolulu Civil Beat

Durham schools face second day of bus delays, district promises swift action, WRAL

Parents Scramble to Get Kids to School as Bus Shortage Hits St. Louis — Again, The 74

Back-to-School Issues Around the US

The School Year Is Off to a Hot Start—Again. What Districts Need to Know, Education Week

What’s in: Nostalgic school supplies. What’s out: Leggings and cellphones, Axios

Top legal hurdles facing schools in 2024-25, K-12 Dive

Snuggles, pep talks and love notes: 10 ways to calm your kid’s back-to-school jitters, NPR

As a New School Year Begins, Ensuring All Students Feel a Sense of Belonging, The 74

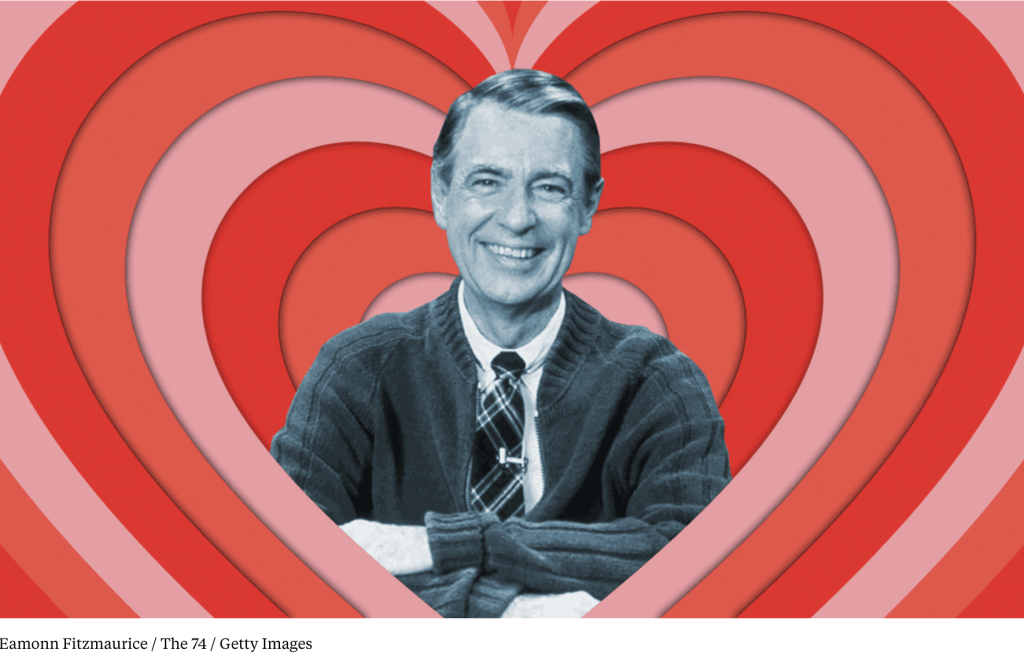

Learning and Love: A Lesson from Mr. Rogers for the Start of a New School Year, The 74

Alabama

No Crocs, hoodies, backpacks? Figuring out shifting Alabama school dress codes, AL.com

Massachusetts

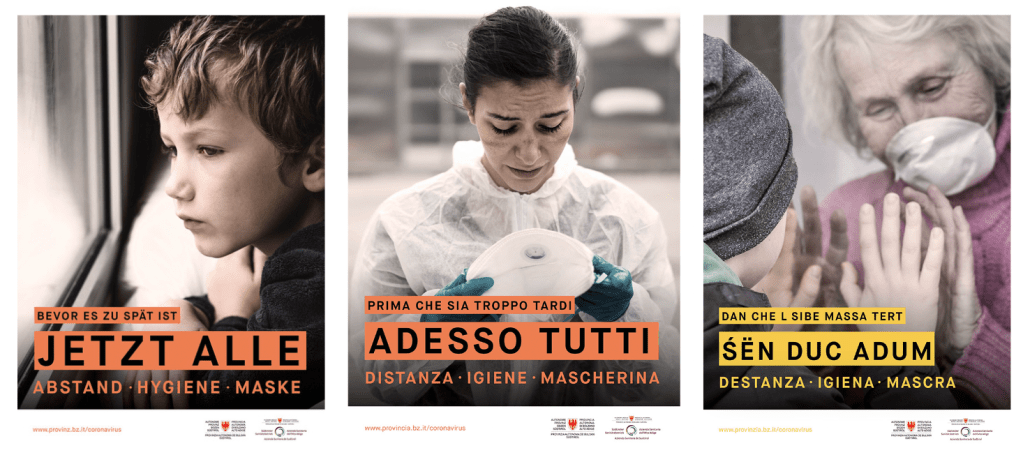

Back to school, back to COVID safety. What to know about best health practices in classrooms, The Boston Globe

California

New laws impacting education go into effect as the school year begins, EdSource

Legislation going into effect this school year will bring changes to California campuses. One new law requires elementary schools to offer free menstrual products in some bathrooms and another requires that all students, beginning in first grade, learn about climate change.

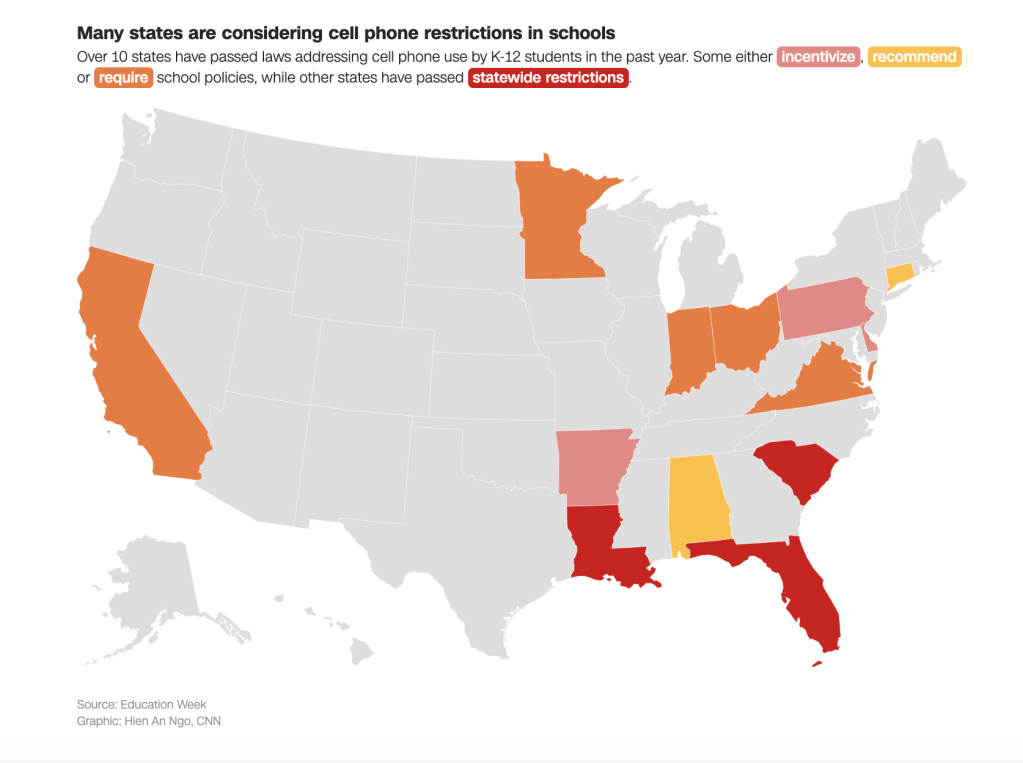

Students heading back to school may have cell phones banned as more states pass laws limiting use, WSB-TV

Too many kids are going back to school this month without functioning A/C, Los Angeles Times

LAUSD students are back to school with street safety measures in place and a cell phone ban, CBS News

Local school districts announce schedule changes amid record temps in Southern California, KTLA 5

Chicago

Chicago Public Schools heads back to class amid extreme heat, Chalkbeat

Florida

New metal detectors delay students’ first day of school in one South Florida district, AP

Each of the district’s high schools was allocated at least two metal detectors to screen their students, with larger schools getting four, like Cypress Bay High School in suburban Weston, which has more than 4,700 students. But even at smaller schools, kids were stuck waiting — leaving students and parents with more than the usual first-day nerves.

Iowa

Michigan

Cellphone bans, free meals, student funding: What to know as Michigan heads back to school, Detroit Free Press

New York City

Literacy overhaul to ChatGPT: 5 NYC education issues we’re watching this school year, Chalkbeat

Elementary school teachers and students will continue to adjust to the city’s literacy curriculum mandate. Schools will still grapple with how best to meet the needs of the thousands of asylum-seeking and other migrant students who have entered the school system. And tensions fueled by the Israel-Hamas war could persist in school communities this year.

Thousands of NYC special ed students denied services days before school starts, New York Post

With high-fives and dance moves, NYC’s nearly 900,000 students return for first day of school, Chalkbeat

New Pencils, New Folders … and New Schools, The New York Times

Seattle

Seattle Public Schools students return as district prepares for a year of change, The Seattle Times

For some historical perspective on how the issues have evolved since the school closures of the COVID-19 pandemic, explore the back-to-school headlines from previous years:

- Fall 23: Crises and Concerns: Scanning the 2023-24 Back-To-School Headlines (Part 1) Natural Disasters, Climate Change and the Start of School in 2023: Scanning the Back-to-School Headlines (Part 2); Educational Issues in the News Across the US: Scanning the Back-to-School Headlines (Part 3)

- Fall 22: Hope and trepidation: Scanning the back-to-school headlines in the US; “Over it” but unable to escape it: Going back to school with Covid in 2022; Going back to school in 2022 (Part 3): Scanning headlines from around the world;

- Fall 21: Going back to school has never been quite like this (Part 1): Pandemic effects in the US; Going back to school has never been quite like this (Part 2): Quarantines, shortages, wildfires & hurricanes;

- Fall 20: What does it look like to go back to school? It’s different all around the world…;

- Fall 19: Headlines around the world: Back to school 2019 edition.